How do early career researchers at BSS experience work during COVID-19?

The current situation, in which a worldwide pandemic resulted in the closure of the university for several months and transition to online teaching, likely affects early career researchers (ECRs) in particular ways, an issue also recognized by the VSNU and other stakeholders. To inform the discussion and understand the problems and needs of our community, YESS BSS (a network that aims to represent and be a voice for early career researchers at the Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences) conducted a survey on how early career colleagues experience the current situation. Below, we summarize the findings along with a response of the Faculty Board. We also contextualize these findings in the larger academic context and call upon the faculty to specifically address concerns regarding declining research progress and mental health.

Summary of survey findings

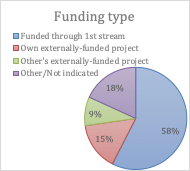

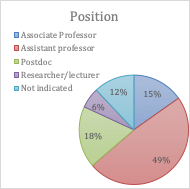

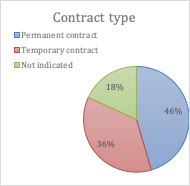

Mid-April, approximately 100 ECRs in the faculty were invited to participate in the survey, of which 33 participated. The distribution of respondents across contract types is depicted below:

Large differences appeared in the number of effective work hours: from around 25% of normal hours to 100% plus (up to 12 hours per week) overtime. Whereas childcare seems to be the most important factor in affecting peoples’ ability to work their contractual hours, some respondents also indicate that stress affects them mentally and affects their ability to work. We are worried about colleagues indicating moderate to severe impact on their mental health and a lack of support from supervisors.

“Large differences appeared in the number of effective work hours: from around 25% of normal hours to 100% plus (up to 12 hours per week) overtime.”

We asked a range of open questions on the effects of the closure on peoples’ research activities. Those with children at home indicated that their research has slowed down considerably or has even stopped completely due to childcare and home-schooling. Also, greater investment in teaching due to the transition to online teaching has meant that people have much less time for research. As one would expect, most people do not have fully-equipped offices at home. Working on a (shared) computer or laptop screen rather than with two screens on a proper desk, with no printing facilities or good office chair is not conducive to research productivity. But not only practical constraints were noted; respondents also suggested that stress, worries about friends and family members, concentration issues and lack of exchange and discussion with colleagues has taken a toll on productivity. Many projects rely on data collected in schools or with patients, all of which have been stopped, which delays projects and appears to make some project plans unrealistic in the proposed time.

We also asked a range of open questions on the effects of the closure on peoples’ teaching activities and practically all who answered this question reported spending (much) more time on teaching, with reasons including design of new exams with open instead of multiple choice questions which requires much more time to grade as well, learning how to use the online teaching environment, and answering an increased number of student emails. Respondents also find online teaching less engaging and note unstable internet connections of some students.

“The experiences of ECRs reported here are quite alarming in two areas: mental health and job insecurity.”

When asked about their biggest concerns for their academic career, respondents note job insecurity due to the threatening economic crisis, whether universities will hire new staff in the near future, and concerns that funded research projects cannot be carried out according to plan, mainly because data collection is paused. Respondents also voice concerns about how their reduced productivity impacts their research output, opportunities for promotion, and ability to meet promotion criteria. In fact, several respondents are afraid not to meet tenure track criteria when their fixed promotion moment approaches, both in terms of publications as well as with respect to grant applications, which respondents do not currently find the time to work on.

Can early career researchers think of possibilities to make-up for these problems? Respondents hope for recognition of the difficulties that many face, and that it will not be possible to work “extra hard” once universities open again because most of us already work the absolute maximum and cannot put in more overtime or become even more efficient. Colleagues also note that project and funding support could be improved to reduce the burden of administrative tasks, or that compensation in reduced teaching load and increased research time in the new academic year would be helpful. Several respondents hope that upcoming promotion procedures will reflect the difficult situation either by extending the period that is being evaluated or by relaxing requirements not only for tenure track steps but also to obtain a permanent contract in general, or by offering extensions to temporary contracts.

Putting the findings in context

The trends observed here align with the struggles reported by other academics and many employees who were forced to work from home during this pandemic. Experts assume that ECRs will be disproportionally affected by the implications of the pandemic as they either have fixed-term contracts or are pre-tenure. There are additional worries about female scientists who often carry extra childcare and household responsibilities. Scientific journals already report that submissions by women have dropped (Larkins & Walker, 2020).

In line with what BSS ECRs report, we see that work hours are split three-ways in a global study of more than 1400 employees: 34% of these employees work reduced hours, 43% work the same number of hours as before, and 21% work longer hours than usual. At the beginning of the pandemic, many employers rose to the challenge and offered additional support for employees to work effectively from home (Keller, Knight, & Parker, 2020). Our faculty joined these efforts and offered support such as additional equipment (e.g., screens) and training (e.g., webinars for teaching online). These investments pay off as employees are more productive when they receive additional support and resources from their employers (Keller et al., 2020). These initial support offerings are incredibly valuable, not only because they enable staff to work effectively, they also signal respect and support for employees during this crisis. However, it is crucial for organizations to follow-up with employee needs. At the beginning of the ‘working from home’ mandate, many employees felt they had sufficient equipment, training, and support. Three months in, we see that it is difficult to maintain productivity at home and better equipment is needed (e.g., well-performing laptops, ergonomic home office equipment, internet connections).

“We can be proud as a faculty that we have moved teaching online so smoothly, but as early career researchers, we are mostly evaluated on research accomplishments – publications, grants, projects that run well.”

The experiences of ECRs reported here are quite alarming in two areas: mental health and job insecurity. During this pandemic, mental health issues have increased dramatically and a global study showed that job insecurity is a contributor to psychological distress (Knight, Parker, & Keller, 2020). Job insecurity refers to the risk of losing one’s job, uncertainty about the future content of the job, and worry about the deterioration of working conditions (De Witte et al., 2010). Clearly, the worries reported here about contracts running out, potentially not meeting the promotion criteria and hence not getting tenure, high pressures to perform, sustained lack of work-life balance, and lack of resources to do high-quality research reflect all components of job insecurity. Unfortunately, so far, we have not received much information on the financial situation of our university or plans to deal with the ongoing crisis. We are aware that some committees are working tirelessly on scenarios that may lay the foundation for communication and information and that these committees need time. At the same time, transparent and active communication about the struggles ahead would help ECRs to understand the situation and cope with these worries. In addition, some findings imply that offering financial support (e.g., to help organize daycare for kids) helps employees to deal with job insecurity and the stress associated with it (Rudolph et al., 2020).

“We ask the faculty to communicate mental health support more prominently and continue to remind supervisors of their role in checking in on early career researchers.”

In summary, what is particularly clear is that research activities are suffering, most prominently for those with children, but also for other colleagues, for a variety of practical and emotional reasons. We can be proud as a faculty that we have moved teaching online so smoothly, but as early career researchers, we are mostly evaluated on research accomplishments – publications, grants, projects that run well. The COVID-19 crisis and closure of universities jeopardize our progress in these domains and we call on the faculty to recognize this and put the topic on the agenda. Moreover, several colleagues report a strong impact of the situation on their mental health. We are glad that the university has taken measures and that staff can call in for a 30-minute slot of coaching but it is not clear whether this information reaches everyone and whether 30 minutes will be sufficient. We ask the faculty to communicate mental health support more prominently and continue to remind supervisors of their role in checking in on early career researchers.

References

De Witte, H., De Cuyper, N., Handaja, Y., Sverke, M., Näswall, K., & Hellgren, J. (2010). Associations between quantitative and qualitative job insecurity and well-being. International Studies of Management & Organization, 40, 40–56.

Keller, A.C., Knight, C., & Parker, S.K., (2020, May 29). Good news – most employees are as productive at home as in the office. But there is room to improve. Center for Transformative Work Design.

Knight, C., Parker, S.K., & Keller, A.C. (2020, June 2). Tripled Levels of Poor Mental Health: But There Is Plenty Managers Can Do. SIOP Newsbriefs.

Larkins, F. & Walker, K. (2020, May 11). More than 10,000 job losses, billions in lost revenue: coronavirus will hit Australia’s research capacity harder than the GFC. The Conversation.

Rudolph, C.W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S., & Zacher, H. (2020). Pandemics: Implications for Research and Practice in Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice.

Note. Featured image by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash.