Let’s write about sex and gender

One day, an undergraduate student whom I supervised, made me see that the binary question that I had used for measuring “sex” (What is your sex? O male O female) was very much outdated. Until then I did not realize that this single binary question could hurt people who don’t fit into these binary categories. My question even had the potential to scare away some of my precious participants. On that day I decided to improve my methods and start writing inclusively about sex and gender and what I subsequently encountered was a minefield of linguistic do’s and don’ts regarding this issue. In this blog post I bundled my experiences and relevant sources which may help you writing inclusively about sex and/or gender in your next study too.

It was only when I moved from the medical faculty to the social sciences faculty one decade ago that I realised the words “sex” and “gender” mean something different.

Sex and gender are not the core of my research, but I do increasingly consider them important factors in my studies (later in this post I will give you three reasons why). It was only when I moved from the medical faculty to the social sciences faculty one decade ago that I realised the words “sex” and “gender” mean something different. “Sex” refers to the biological attributes of a person that can be measured by physical or physiological variables and refers to the reproductive or sexual anatomy but also to less visible attributes, such as chromosomes, gene expression and hormone levels and function (see Canadian Institutes of Health Research). The word “sex” is thus commonly used in biologically or medically oriented sciences (including psychiatry), which is not very surprising since the variables of interest in this field are mostly physical or physiological in nature. Observed differences between men and women on physical or physiological variables are therefore interpreted as “sex” differences in the biological/medical sciences.

Gender has received much more attention in the behavioural and social sciences than in the biological/medical sciences.

“Gender” on the other hand, is a social construct which refers to all social roles, behaviours, expressions and identities of girls, women, boys, men, and gender diverse people (see the Canadian Institutes of Health Research). Since this is the expertise of behavioural and social scientists, gender has received much more attention in the behavioural and social sciences than in the biological/medical sciences. The majority of people (ca. 95%) are cisgender, meaning that their biological sex or sex assigned at birth (which can be male, female or X in most countries) corresponds to their gender identity. For a minority of people though, biological sex does not correspond to their gender identity. For those, their gender identity can be opposite their gender assigned at birth, can vary between man and woman, or can vary in other ways. The list of gender variations is inexhaustible since the language used for gender identities changes at a fast rate, and is almost impossible to keep track (Fraser, 2018). An important realization when writing about sex/gender differences is that for the large majority asking about their sex or their gender will result in a congruent answer; either they are man or they are women, both by sex and gender. However, there is a minority that we need to take into consideration when writing inclusively about sex/gender.

In a minority of people, biological sex does not correspond to their gender identity. These people make part of the lgbtiq+ community, who make use of the below symbol to express their gender identity.

I’ve learned that the wordings you choose as a researcher need to be very particular when writing in an inclusive way about sex and gender, both in scientific writing and the questions for participants. In the biological and medical sciences it is for example common to speak about “males” and “females” to refer to the two most frequent sexes (in humans as well as animals). The American Psychological Association (APA), however, since 2020 advised against using “male” and “female” as nouns (see the bias-free language section about gender of the 7th APA style). Instead, more specific nouns should be used to name people of specific age groups, e.g. girls and women, and boys and men. When writing in an inclusive and respectful way in general, it is necessary to address people in the way they address themselves (as long as the wordings are specific and unambiguous). For example, I don’t refer to myself as a “female” but as a “woman”, so it is more respectful and inclusive to describe me as such in a research project too. Across large age groups, APA style does allow the use of “male” and “female” as nouns (e.g. females aged 6 to 80 years), and to use “male” and “female” as adjectives whenever relevant (e.g. the female experimenter). Do you get what I mean with the minefield of linguistic do’s and don’ts?

There are three main reasons why sex/gender needs to be included in psychological research.

The first reason is to describe the representativeness of your sample for the population of interest and to be able to replicate the study. Therefore, nearly all researchers need to ask for sex/gender. In the year 2023 you can no longer get away with a binary question, like I’ve been doing for years. Actually, continued use of binary measures for sex or gender reflects poor methodological practice, since the data you will gather is not representative for the larger population. As already pointed out above, binary questions may additionally have negative implications for the well-being and social inclusion of people not identifying with cisgender, which may scare them away from (your) research.

The most basic question you can ask is a multiple-choice question with three answer alternatives for sex and four answer alternatives for gender:

- [categorical sex] What is your sex assigned at birth (as stated on your birth certificate)? O Female O Male O X (unidentified).

- [categorical gender] What is your gender identity? O Woman O Man O I would like to indicate myself O I would rather not share.

Combinations of the suggested questions may provide the most optimal information to describe the number of people reporting incongruent gender identity compared to their sex assigned at birth.

Note that adding an option “other” is advised against, since “othering” categorizes people as different from oneself or the mainstream, which magnifies the difference and may put them in a subordinate position (Johnson and colleagues, 2004). People who are treated as other often experience marginalization, decreased opportunities, and exclusion. Even the “non-woman/men” statements above may be felt as “othering”, so in (expectedly) gender diverse research populations it is wise to only ask the open-ended question “What is your gender identity?” and code your variable afterwards (see Cameron & Stinson, 2019). However, not all (or even the majority of) participants may understand such open question, if they had never (re)considered before how they feel about living with their own sex. In that case, you could opt for an extended multiple choice question or for a fluid question. One best practice extended multiple choice question has been suggested by Fraser (2018), writing from the lgbtiq+ perspective:

- [categorical gender identity] What is your gender identity? Select all that apply. O Man O Woman O Trans man O Trans woman O Non-binary O Not listed. Please state __________________.

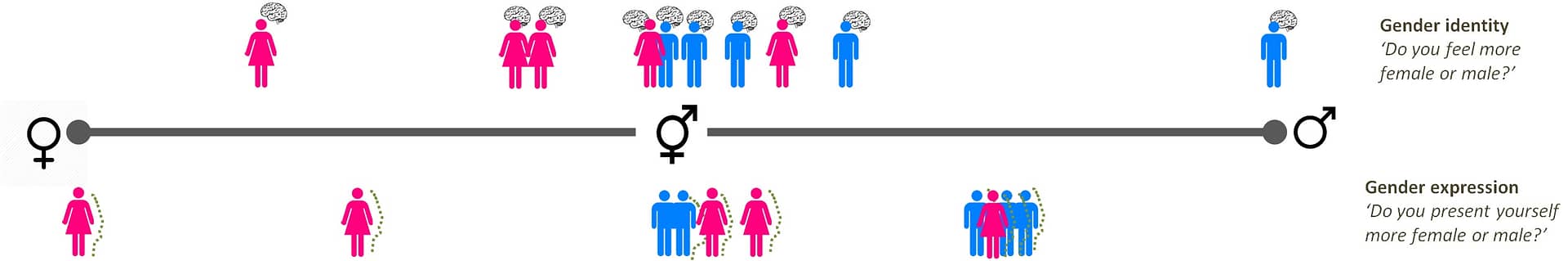

In a collaborative project about autism in women, I recently used a fluid gender question that does not use categories but a slider (or a broad Likert scale), on which participants can indicate how male or female they feel and how male or female they present to the outside world:

- [fluid gender identity] Do you feel more like a woman or a man? Perhaps you feel somewhere in between or you do not have a preference. Move the slider: I feel like: 1 (man)>>>50 (no preference)>>>100 (woman).

- [fluid gender presentation] How do you present yourself to the outside world? Is this more ‘male’ or more ‘female’? For example, think about the clothes you wear, how you act with others, what kind of hairstyle you have, etc. Move the slider: I present myself as: 1 (man)>>>50 (no preference)>>>100 (woman).

This type of question may be helpful for exploring gender variation in your population, by creating a figure such as the one below.

In a sample of autistic people we found fairly neutral gender identities, while gender expression was more varied (the male and female pictograms refer to the participant’s sex assigned at birth).

A second reason for including sex/gender in research, is to select your sample based on sex or gender, for example when you are studying specific samples of women, men, intersex or gender diverse people. It is highly important to think critically and discuss with your fellow researchers whether it is desirable to exclude participants based on their sex/gender. In the past, women were oftentimes excluded from medical studies for a long time, at first to protect them for harmful effects, but later because it was common practice or just too complicated to deal with their unpredictable and fluctuating hormonal system (Mosconi, 2020; Tannenbaum et al., 2019). Currently, there is a counterreaction of research focusing on girls/women only, and by doing so we might be unnecessarily excluding men! Sex/gender inclusive research includes both men and women, and analyses may be stratified (more on this next). Also, we might be unnecessarily excluding intersex/gender diverse people, particularly when we start using “gender inclusive” questions like the ones above to describe our samples. When using the answers to those questions to exclude people from our samples, we are not conducting inclusive research. It might not be necessary after all to exclude them from our research, just because it is common practice, too complicated to measure or too complicated to analyse. You may provide descriptives for the lgbtiq+ group, and contribute to accumulating knowledge for this understudied group (see p. 352 of Fraser (2028) for a discussion).

When using the answers to “gender inclusive” questions to exclude people from our samples, we are not conducting inclusive research.

Thirdly, you may want to stratify your analyses according to sex or gender to be able to judge whether your findings apply to men, women and/or gender diverse people. Even though many textbooks and articles minimize sex and/or gender differences for example by stating that “men and women are more alike than they are different”, for certain research topics, sex and gender do matter dramatically (Lippa, 2006). Sex and gender may for example influence the prevalence and expression of mental health problems, which is relevant to (clinical) psychology. The neurodevelopmental conditions attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism are more prevalent in boys/men and express differently in girls/women (Kok, 2021), while mood and anxiety disorders on the other hand are more prevalent in girls/women and may express differently in boys/men (Li et al., 2022; Bandelow & Michaelis, 2015). Interestingly, gender variations appear to be more common in neurodiverse people too (Strang et al., 2014). For certain research questions, it is therefore crucial to include sex and/or gender as a factor and this all starts with knowing your sex/gender inclusive questions.

For certain mental health research topics, sex and gender do matter dramatically.

Even when sex and gender are not the main topic of your research, it is necessary to choose your sex- and/or gender-related questions and wordings wisely, at least if you want to conduct methodologically sound research. I hope to have cleared most of the mines in the minefield of writing about sex and gender and that you are up to sex/gender inclusive research now.

Further education

Via e-mail you can request my sheet of sex/gender questions including the considerations with each type of question: y.groen@rug.nl.

Two free online workshops on the inclusion of sex and/or gender in scientific research are available from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research here. After completion, you will receive a certificate which you can list on your cv.

For more information in the Dutch language, you may consult the “Genderdoeboek” of the Dutch Transgendernetwerk.

Broaden your scope on sex and gender by visiting the University Museum of Groningen for the exhibition PHALLUS. Norm & Form, developed by GUM (Ghent University Museum), which takes you on a journey through our ideas on sex, gender, science, norms and values. It runs from May 26 2023 till February 25 2024.

References

Bandelow, B., & Michaelis, S. (2015). Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. www.dialogues-cns.org

Cameron, J. & Stinson, D.A. (2019). Gender (mis)measurement: Guidelines for respecting gender diversity in psychological research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12506

Fraser, G. (2018): Evaluating inclusive gender identity measures for use in quantitative psychological research, Psychology & Sexuality, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1497693

Johnson, J. L., Bottorff, J. L., Browne, A. J., Grewal, S., Hilton, B. A., & Clarke, H. (2004). Othering and being othered in the context of health care services. Health Communication, 16, 255–271. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1602_7

Kok, F. M. (2021). The female side of ADHD and ASD (PhD thesis). University of Groningen. https://doi.org/10.33612/diss.179073089%0D

Li, S., Xu, Y., Zheng, L., Pang, H., Zhang, Q., Lou, L., & Huang, X. (2022). Sex Difference in Global Burden of Major Depressive Disorder: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.789305

Mosconi, L. (2020). The XX brain. The groundbreaking science empowering women to prevent dementia. Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books, London.

Lippa, R. A. (2006). The gender reality hypothesis. American Psychologist, 61, 639–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.639

Strang, J.F., Kenworthy, L., Dominska, A., Sokoloff, J., Kenealy, L.E., Berl, M., Walsh, K., Menvielle, E., Slesaransky-Poe, G., Kim, K.E., Luong-Tran, C., Meagher, H., Wallace, G.L. (2014). Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 43, 1525-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0285-3

Tannenbaum, C., Ellis, R.P., Eyssel, F., Zou, J. & Schiebinger, L. (2019). Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature, 575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1657-6

Image credits

Featuring image adopted with permission from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The gender symbol was taken from PNGEGG.

The figure about gender identity and expression in autistic people was created by Daria Henning and Sigrid Piening in the context of the Elucidating Female Autism Study and I am thankful for their permission to use it in this post.

Acknowledgements

I thank Sigrid Piening and Yasin Koc for proofreading this blog post.

Thanks for this thoughtful and stimulating essay. Years ago, a few students and I wondered what topic might be lacking in our Faculty’s education. We all agreed on gender. We actually had a voluntary course twice, which went well (but also meant significant extra work, while everyone got overworked).

Reviewing the research literature, our conclusion was sobering: that most “gendered” research merely replaced the binary “sex” with a binary “gender” question (like replacing “transsexual” with “transgender”, merely linguistically). I hope that this has changed in the meantime!

The scale you were using to investigate gender identity and expression looks promising. I wondered how the colors related to it? Was that the subjects’ assigned sex?

P.S. Just in case you don’t know the documentary “Genderbende” yet, I can really recommend it!

The pictograms in the figure about gender identity indeed portray sex assigned at birth. I added this to the blog post. Thanks for your rhoughtful comment and the documentary tip! Yvonne