Coordination in development: Caregiver-child synchrony

“Ah… da da da da da da … oh doe doe doe doe… eeh aah oeh” … Which adult hasn’t said something similar, while talking with a baby? When people interact with babies, they tend to imitate babies’ vocalizations, and mimic their behavior in general (see first video, below). Furthermore, also babies imitate people that they are interacting with. A funny example is babies who stick out their tongue, when an adult does so first.

Imitating each other’s behavior falls under the larger phenomenon of synchrony between humans, which is essential for attunement and interactions (see also this duo-interview about social coordination). Moreover, synchrony between caregiver and child has received special research attention. This is because caregiver-child synchrony is important for infants’ cognitive, social and emotional development [3][4]. In addition, difficulties in caregiver-child synchrony have been linked to autism [14][15] and ADHD [16].

What is caregiver-child synchrony?

Caregiver-child synchrony is an interaction pattern that is 1) regulated by both caregiver and child, 2) two-way, by involving turn-taking for example, and 3) harmonious [1][2][3][4][5]. In other words, caregiver-child synchrony is dyadic, which means that both child and caregiver actively contribute to this interaction pattern [6][7][8]. Furthermore, timing is an important element of synchrony. That is, caregiver-child synchrony is a match between the child’s and caregiver’s behavior in time [2].

These characteristics of caregiver-child synchrony are also visible in the first video. Both mother and daughter regulate the interaction, as both initiate and break off sequences of behavior, thereby contributing to the interaction. Mother and daughter take turns, by alternating their vocalizations and periods of activity. This turn-taking is a match of behavior in time, as one of them ‘speaks’ while the other one ‘listens’ – in harmony. Also other actions that complement each other, such as when the mother holds up her hands and the baby kick against them, or imitation (with or without a delay) are examples of matches of behavior in time.

How to research caregiver-child synchrony?

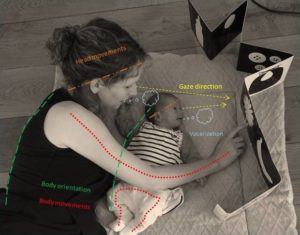

Although examples of caregiver-child synchrony are abundant in natural interactions, caregiver-child synchrony is difficult to quantify. Thus far, caregiver-child synchrony has primarily been studied using categorical observation data [1][2]. For instance, a researcher could look at the first video, decide which behaviors are important for synchrony, and code at which time in the video these behaviors occur. However, synchrony between caregivers and their infants is often more subtle and diverse than similar behaviors occurring at the same time. Instead, caregiver-child synchrony often involves so-called cross-modal matches, i.e. matches in different modalities. For example, a caregiver’s voice gets louder when the infant kicks his/her legs faster [7]. The figure on the right illustrates how many different modalities and measures one could look at when studying caregiver-child synchrony – and isn’t even exhaustive.

Although examples of caregiver-child synchrony are abundant in natural interactions, caregiver-child synchrony is difficult to quantify. Thus far, caregiver-child synchrony has primarily been studied using categorical observation data [1][2]. For instance, a researcher could look at the first video, decide which behaviors are important for synchrony, and code at which time in the video these behaviors occur. However, synchrony between caregivers and their infants is often more subtle and diverse than similar behaviors occurring at the same time. Instead, caregiver-child synchrony often involves so-called cross-modal matches, i.e. matches in different modalities. For example, a caregiver’s voice gets louder when the infant kicks his/her legs faster [7]. The figure on the right illustrates how many different modalities and measures one could look at when studying caregiver-child synchrony – and isn’t even exhaustive.

Next to caregiver-child synchrony being cross-modal, it is also non-linear. To explain what this means, we will first illustrate what linear synchrony is. Most analyses of caregiver-child synchrony have been linear [1][2], which means that they’ve looked at behaviors that happened at the same time, and at how more (or less) behaviors of caregiver or child are related to more (or less) behaviors of the other. In the first video, someone could for instance count how often mother and daughter vocalize the same time, or count how often they both vocalize and see if they do this to a similar degree.

Synchrony, however, is a typical nonlinear, dynamic process [13]. For instance, instead of smooth changes over time, abrupt shifts can occur, such as sudden transitions from in-synchrony to out-of-synchrony. In the first video, periods of bursts of activity and periods of inactivity interchange, with the baby initiating the latter by looking away. Moreover, the effects of small changes are not always of the same magnitude [11][12]. Instead, small changes can have large consequences, depending on the history of the child and caregiver. For example, a caregiver-child dyad that has, over time, become very sensitive to disruptions may take longer to synchronize again after a short interruption than another dyad without this history. Such nonlinear features of synchrony can’t be captured with linear tools, however.

Open questions about caregiver-child synchrony

The good news is that new (nonlinear) tools exist that can provide a more complete picture of the dynamic interaction between caregiver and child. For example, time series of continuously measured behaviors, such as movements and vocalizations, would greatly add to the study of caregiver-child synchrony. Continuous measurements, as opposed to observing categorical behaviors, are able to capture the more subtle attunement between caregiver and child. Furthermore, analyses exist that capture behavioral sequences, both on the short-term (i.e. one turn) and more long-term (i.e. whole interaction) [9][10][11][12]. Thereby, such analyses grasp nonlinear features such as sudden transitions, and history-dependence – the so-called dynamics of the interaction.

Learning more about the dynamics of caregiver-child synchrony is important for two reasons. 1) The dynamics of caregiver-child synchrony are the foundation for future social interactions. 2) More insight in these dynamics provide opportunities to accommodate caregiver-child synchrony when this doesn’t happen as smooth and naturally, such as for children with autism or ADHD and their caregivers. You probably never thought that your “da da da”s and “doe doe doe”s were so important!

Recently a consortium of researchers from five Dutch universities has formed, with plans to investigate coordination in autism, ADHD & typical development. Both Steffie van der Steen and Lisette de Jonge-Hoekstra, who wrote this blog post together, are part of this consortium. In this project, we aim to utilize such new nonlinear tools as described above, to come to a more fundamental understanding about multi-modal coordination and synchrony in typically developing children and children with autism and ADHD. Moreover, based on these new, nonlinear tools, we aim to develop accessible tools to capture this multi-modal coordination and synchrony.

More information about the project can be found on our website.

Note: Photo by Picsea on Unsplash.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the importance of caregiver-child synchrony in development, highlighting its significance for cognitive, social, and emotional growth in infants. The exploration of synchrony as a dyadic, two-way interaction pattern regulated by both caregiver and child sheds light on its complexity. Moreover, the discussion on nonlinear dynamics and the need for advanced tools to study synchrony offers valuable insights into future research directions. The interdisciplinary approach taken by the consortium of researchers from Dutch universities, aiming to investigate coordination in autism, ADHD, and typical development, holds promise for enhancing our understanding of synchrony across different modalities. Overall, this article underscores the crucial role of caregiver-child synchrony and the potential implications for supporting children’s development, particularly those with developmental disabilities like autism and ADHD.