The subtle spreading of sexist norms

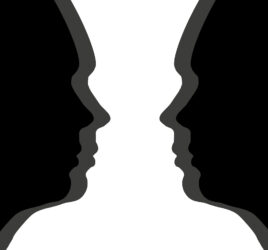

Illustration by Tomi Um.

Suppose you are in a conversation and someone makes a sexist remark. How do you respond? Do you actively confront the sexist person by engaging in discussion? Do you fall silent in search of a response? Or do you swiftly switch topics to avoid an awkward situation? In our recently published set of studies, we examined how such responses may contribute to (or undermine) the spreading of sexist norms.

While sexist or racist expressions are already frequent in daily life, on television the prevalence of sexist expressions and gender stereotypic role models is even higher. This is especially important to consider, because the potential influence of televised conversations in transmitting sexist norms is much higher, simply because they are observed by a large audience.

For every racist or sexist expression that one encounters, one may ask oneself: Is this just a lone sexist wolf talking, or does this view reflect public opinion? Therefore, our research asked: When do people see sexist remarks as “normal”—that is, an opinion that is okay to be expressed in social settings and that is shared by most people in society?

“When do people see sexist remarks as “normal”—that is, an opinion that is okay to be expressed in social settings and that is shared by most people in society?”

To find out whether an expression reflects a social norm, we examined the role of the conversation partners. Indeed, how others respond to a sexist statement should determine whether sexism is seen as socially acceptable and shared by other people, or not. Now of course, this would be pretty obvious if the other people explicitly agree or disagree with a sexist statement. But we know from research that most people prefer not to explicitly confront sexism, because they may fear negative consequences, such as being disliked or being seen as oversensitive or as troublemakers. Instead, many people are inclined to respond to controversial statements rather ambiguously. One thus needs to search for subtle cues that may indicate disagreement or agreement in a conversation.

Conversational Flow

One such cue is conversational flow. Our previous research demonstrated that people derive important information about their relationships from the flow of a conversation. When a conversation smoothly flows, they see this as a signal that things between them are okay. But flow does more. It also gives people the feeling that they are on the same wavelength, that they agree on the issue. This raises the question: If we smoothly continue a conversation after a sexist statement is made, would others infer that we agree with the sexist statement? Our research shows that this is indeed the case.

“This raises the question: If we smoothly continue a conversation after a sexist statement is made, would others infer that we agree with the sexist statement? Our research shows that this is indeed the case.”

In three studies, students watched one of three videos of a smoothly flowing conversation among five male students. In two versions, a few minutes into the conversation, one of the males says: “Women just don’t have these natural leadership qualities.” We manipulated the response of the other students after this statement. In the “flow” version, students saw a video in which the sexist statement was followed by a smooth continuation of the conversation (in which the others did not give their opinion on the statement). In the “silence” version, the other students paused for about 3.5 seconds after the sexist statement was expressed, before they continued as in the flow version. The third version was a control version in which the same video was edited such that no sexist statement was shown.

It appeared that the students who saw the flow version perceived the norm to be much more sexist than students who saw either of the other two versions. The smooth continuation of the conversation after the sexist remark was thus taken to indicate that the statement was socially acceptable and shared by the other male students in the video. Flow served as a proxy for agreement. Importantly, the effects generalized to more sexist norms in general: students who watched the flow version (compared to the other versions) felt that male students, in general, would share the sexist belief that was expressed.

Silence as a Corrective

So how to counter this subtle spreading of sexist norms? For this, we need to look at the “silence” version. Importantly, students who watched the silence version did not perceive the norms to be any more sexist than those watching the control version in which no sexist statement was made. That means the silence functioned as a signal that the sexist statement was unacceptable and not shared by the other group members. As such, the silence was a tool to ‘correct’ the sexist norm breach.

What can we learn from this? On the one hand, the results can be seen as a warning: we should be aware of the risk of contributing to the spreading of sexist norms if we keep up the flow of a conversation after a sexist statement. But there’s also a perk: the studies hand us a simple tool that we can use to confront sexist remarks, even when we don’t have all arguments to engage in discussion. Simply allowing the conversation to be awkward for a few moments may be enough to communicate that sexism is simply unacceptable.

“But there’s also a perk: the studies hand us a simple tool that we can use to confront sexist remarks, even when we don’t have all arguments to engage in discussion.”

(When Justin Trudeau paused for 21 seconds when asked to comment on Trump’s handling of Black Lives Matter protesters, some saw it as his way of expressing disapproval).

Reference

Koudenburg, N., Kannegieter, A. Postmes, T., Kashima, Y. (2020). The subtle spreading of sexist norms. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220961838.