Social inclusion in diverse work settings

“Man is by nature a social animal.”

– Aristotle, Politics

This famous quotation from Aristotle is at the heart of my dissertation. It reflects that groups are essential to humans. We depend on others for our food, housing, and safety. Hence, most of us are unable to survive without the help of others (Caporael & Baron, 1997). Besides serving our material interests, inclusion into groups also has important psychological benefits (Correll & Park, 2005). Being part of a group enhances our self-esteem (Leary & Baumeister, 2000), reduces our uncertainties (Hogg & Abrams, 1993), and makes us feel distinct from others outside the group (Brewer, 1991).

Considering that inclusion into groups is so vital to our well-being, researchers have devoted substantial effort to investigate how inclusion is established, and, more specifically, in which type of groups we tend to seek inclusion. Generally, we prefer to be part of groups whose members are similar to ourselves (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005). However, we cannot always freely choose our fellow group members. One context in which this is particularly true is the work domain. We usually have little control over whom we work with. Accordingly, despite our general preference for similar others, we often need to collaborate with people that have different opinions and values or are different from us in terms of age, gender, or ethnicity.

The positive side of diversity

Yet, despite the difficulties diversity may bring, it is not just bad news. Diversity has potential benefits to both individuals and organizations. Being included in diverse work groups and organizations may enlarge one’s social network (Granovetter, 1973) and expands our worldview (Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Being part of diverse work environments has even been found to enhance our well-being (Van Dick & Haslam, 2012). Likewise, for organizations, diversity may be a source of strength, rather than a necessary evil. Having a diverse workforce can improve internal work processes, may enlarge the organization’s external network, and can improve the moral image of the organization (Ely & Thomas, 2001).

However, for these benefits to occur, people of all backgrounds need to feel included. Hence, it is essential to understand how inclusion in diverse work settings can be fostered. This was the central aim of my dissertation. As a first step, based on existing definitions and theoretical insights, we defined inclusion as the extent to which an individual perceives that the group provides him or her with a sense of belonging and authenticity. In other words, being included means that you belong and can be yourself within a group. Based on this definition, a scale to measure individual perceptions of inclusion was developed and validated (Jansen, Otten, Van der Zee, & Jans, 2014).

“the organization’s ideology with respect to diversity influences whether employees feel included”

Second, this newly developed scale was used in a number of studies to determine how organizational diversity policies affect employees’ inclusion perceptions. Here, we distinguished between employees belonging to the demographic majority (the Dutch) and those belonging to the demographic minority (people from non-Western descent). The results showed that the ideological vision of an organization with respect to diversity plays an important role in creating feelings of inclusion. Interestingly, there was a crucial difference between majority and minority members in this respect. Majority members experienced more inclusion if their organization emphasized that demographic differences between employees were irrelevant. Minority members, however, experienced more inclusion if they perceived that their organization acknowledged and appreciated differences (Jansen, Vos, Otten, Podsiadlowski, & Van der Zee, 2015). Furthermore, the results indicated that majority members experienced more inclusion and supported organizational diversity efforts to a greater extent when their organization explicitly acknowledged that majority members play a crucial role in diversity management (Jansen, Otten, & Van der Zee, 2015).

Together, the results of my dissertation demonstrate that experiencing social inclusion at work is vital for the well-being and performance of employees. It also shows that the organization can play a central role in promoting their employees to feel included. However, how inclusion is established differs between majority and minority members.

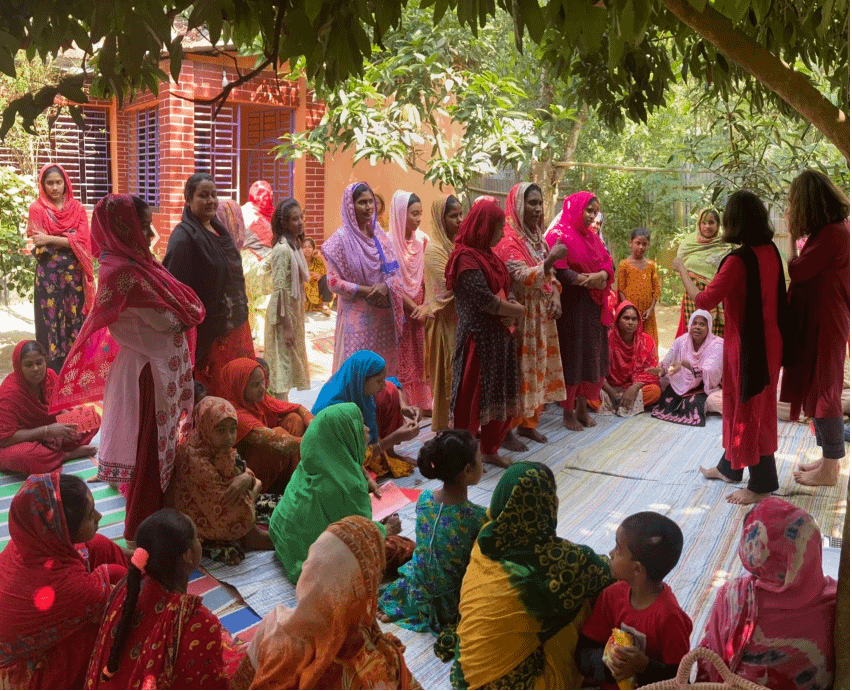

Note: Picture is the cover of Jansen’s dissertation designed by studio0404.nl.

References

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475-482. doi:10.1177/0146167291175001

Caporael, L. R., & Baron, R. M. (1997). Groups as the mind’s natural environment. In J. A. Simpson, & D. T. Kenrick (Eds.), Evolutionary social psychology (pp. 317-344). Hillsdale, NJ England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Correll, J., & Park, B. (2005). A model of the ingroup as a social resource. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(4), 341-359. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_4

Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(2), pp. 229-273.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1993). Towards a single-process uncertainty-reduction model of social motivation in groups. In M. A. Hogg, & D. Abrams (Eds.), Group motivation: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 173-190). Hertfordshire, HP2 7EZ England: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Jansen, W. S., Otten, S., & Van der Zee, K. I. (2015). Being part of diversity. the effects of an all-inclusive multicultural diversity approach on majority members’ perceived inclusion and support for organizational diversity efforts. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, doi:10.1177/1368430214566892

Jansen, W.S., Vos, M.W., Otten, S., Podsiadlowski, A., & Van der Zee, K.I. (2015). Colorblind or colorful? How diversity approaches affect cultural majority and minority employees. Journal of Applied Social Psychology.

Jansen, W. S., Otten, S., Van der Zee, K. I., & Jans, L. (2014). Inclusion: Conceptualization and measurement. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(4), 370-385. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2011

Kristof-Brown, A., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281-342. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 32. (pp. 1-62). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press.

Roccas, S., & Brewer, M. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 88-106. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01

Van Dick, R., & Haslam, S. A. (2012). Stress and well-being in the workplace: Support for key propositions from the social identity approach. In J. Jetten, C. Haslam & S. A. Haslam (Eds.), The social cure: Identity, health and well-being (pp. 175-194). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press.