Psychedelics: Trip or Treatment?

Scholars in Groningen debated the present and future of psychedelic drugs. Will they revolutionize medicine?

On November 28, 2022, Mindwise and Studium Generale Groningen jointly organized a formal debate on psychedelics, facilitated by Valeria Cernei. The proposition was: The therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs challenges the Western biomedical paradigm. Given the huge public and scientific interest, not the least among students, it was not surprising that the event sold out long in advance.

A short history

After a period of increasing research on psychedelics – mostly LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) and psilocybin – in the 1950s and 1960s, these substances were increasingly demonized and prohibited in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, an international treaty regulating cannabis, cocaine, and opium, the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 extended the strict governmental control to psychedelics.

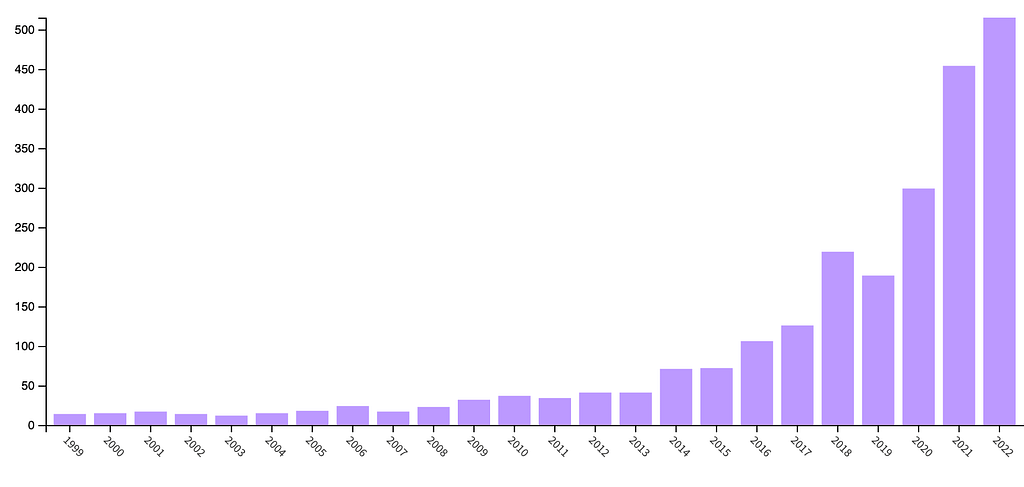

That regulation, which often meant complete prohibition, also made it very difficult for scientists to further investigate the potential of these substances as treatment, particularly in the field of clinical psychology and psychiatry, but also palliative medicine. However, since the 1990s, this kind of research is increasingly pursued again, particularly with psilocybin, a psychedelic compound naturally present in some kinds of mushrooms (Kyzar et al., 2017). Until now, the annual number of journal publications actually increased more than 30-fold (Figure 1).

The debate

Considering this amount of attention these substances now receive in clinical and basic research, to also better understand how the nervous system works and how its function is related to subjects’ well-being and experience, the dichotomy of trip or treatment hardly seems to be at issue any more. Whether psychedelic drugs challenge the Western biomedical paradigm thus promised a more active debate.

On the affirmative side:

- Berend Pot (PhD student in philosophy, University of Groningen)

- Jon Keller Munoz (psychology student, University of Groningen)

- Pamela González Dávila (researcher in biomolecular sciences, University of Groningen)

The affirmative side – thus the three scholars who believed that the findings on psychedelics cannot be integrated into the present biomedical approach – criticized “reductionistic” research and advocated a “holistic” alternative. It were impossible to understand how and why these substances work only on the biological level. The psychedelic experience and what it means to the substance user had to be understood as well.

On the contradicting side:

- Caroline Murphy (University College student, University of Groningen)

- Jurriaan Strous (psychiatrist, University Hospital Amsterdam)

- Morten Lietz (behavioral and cognitive neuroscience, University of Groningen)

The contradicting side reacted with a two-fold strategy: On the one hand, psychiatrists were already trained to include holistic approaches, to consider personal meaning, spirituality, and even mystical experiences in clinical practice. On the other hand, mechanisms like neuroplasticity (i.e., the ability of neurons to build new connections) and dose-dependent effects (i.e., correlations between the amount of the substance consumed and the consumer’s experience) suggested that psychedelics can be included into the biomedical paradigm.

Do we need new clinical experts?

A rather practical, yet not less significant part of the debate focused on whether a new kind of clinical expert is necessary for treatments with psychedelic substances. The affirmative side emphasized the importance of indigenous knowledge, the role of a culture in which such treatments have been embedded for ages, and the function of experienced shamans or spiritual leaders.

Their opponents, however, were concerned about quality control. They referred to recent scandals involving “shamans” and pointed out that different kinds of healthcare professionals should ideally work together in a team. But they also stressed that in clinical practice, there were never 100% certainty of success. Yet: “Psychedelic experience is measurable in the way the human mind is measurable.”

The debate thus led to basic and foundational questions of what it means to be human, of qualitative vs. quantitative research as well as subjectivity and objectivity in science. Perhaps it would make sense to distinguish between clinical practice and education on the one hand and scientific research on the other in follow-up debates. After all, dealing with patients and their issues is different from getting a journal article published, although the two endeavors ideally inform each other.

It should be clear that such deep and complex issues cannot be resolved within an hour. Since the event was recorded and is still available on YouTube, the discussion and investigation can continue even after it ended in the great hall of the University of Groningen.

Previously on Mindwise: Psychedelics: New Chance or New Hype for Psychology?

References

Kyzar, E. J., Nichols, C. D., Gainetdinov, R. R., Nichols, D. E., & Kalueff, A. V. (2017). Psychedelic drugs in biomedicine. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 38, 992-1005.