I love you

Those wonderful, difficult words have such power. Saying them too early is awkward. But waiting too late can lead to a lifetime of missed opportunities for happiness. This is something everyone comes to understand eventually.

I have loved; been in love; fallen out of love. I have resisted saying those words when I should have. I have felt awkward when I shouldn’t have. I even had a relationship end over them. After that, I resisted saying them for years.

Still, I never really thought about the power of those words until a masters student here in our Reflecting on Psychology graduate programme, Iris van der Wal, proposed a thesis on the topic. It’s a fascinating, challenging project: the more you look at it, the more complex it gets. (Indeed, the Proquest Dissertation database—to which we have a subscription—lists several hundred recently-completed projects.)

One might be tempted to reduce this to a discussion about sexuality. Granted, there’s lots of interesting scholarship on that theme. (See, most notably, Michel Foucault’s four-volume History of Sexuality.) But that’s not especially interesting—well, not to me. Nor do I mean to talk about romance or gender-differences. Or biology (or evolutionary biology). What I want to focus on instead are the words themselves: their “emotional weight,” as one peer-reviewed study put it, in which how the words feel changes according to cultural context (and also by demographic).

In other words, I want to talk about meaning. In this case, my focus is on felt-meaning. I’m curious about where this power comes from, and how that higher-order what-it-is-like constrains what-it-is-you-can-mean when using the same words across boundaries (see e.g., Burman, 2012a, 2012b; 2014; 2015; 2018; in press; Burman, Green, & Shanker, 2015).

Our student’s motivation is different from mine, of course, but it got me thinking. It made me reflect on my life, as well as on psychology.

I have a friend in Canada who says he loves me every time we talk. It’s part of how he says goodbye. His wife and children say it to me too. But I hadn’t been able to say it back. After more than ten years of hearing it. Then I just decided one day that I would: my friends rallied around me when my own marriage ended, and I felt supported—loved—through that most difficult period of my life.

One day, we talked on the phone like usual. I knew I wanted to say the words when he did. It felt meaningful, and so difficult. I was trembling.

When the call ended, he signed off as usual. And I did something different: “I love you too.” He didn’t even seem to notice. Except for the smile that I’m sure I heard as he hung up.

I had made it into a big deal. For him, it wasn’t nothing. But it also isn’t taboo.

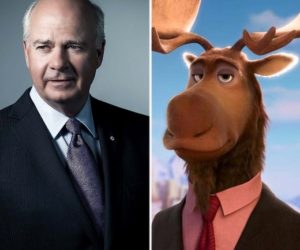

There was a famous rock singer in Canada, Gord Downie, who didn’t just say “I love you.” He kissed his friends on the mouth. He even kissed our most famous newsman, Peter Mansbridge, who is known better here in Europe as Peter Moosebridge (from Zootropolis). On the mouth!

Figure 1. Peter Mansbridge (left) and Peter Moosebridge (right)

I couldn’t do that. Downie did it every day. It was normal.

When he died a year ago today, on the 17th of October 2017, the entire country cried. We all loved him, and his band: “The Tragically Hip.” (I recommend starting with New Orleans is Sinking, but my favourite of their many songs—for a variety of reasons—is Bobcaygeon.)

The Hip’s last concert was shown live on television by the national public broadcaster, not long after the diagnosis of the brain cancer that killed its lead singer and songwriter. It was watched by millions. Even our prime minister, Justin Trudeau, cried at the loss of our nation’s friend.

Downie was loved. But how many of us told him? More importantly, how many of his friends didn’t?

The overwhelming outpouring of emotion upon his death, including by the prime minister, was criticized as unmanly. Yet denying each other now seems inhuman. In light of the one-year anniversary of our collective loss, it even seems inhumane. It’s wrong. So why is it difficult?

After the phone call with my friend, I felt so much better. It was a good thing. And yet we resist.

Figure 2. Gord Downie performing in Kingston, Canada, before his diagnosis. (Photo by David Bastedo.)

When my marriage ended, it felt like I would never love again. I didn’t want to. I still don’t: it hurts. Suppose, though, that the words themselves don’t have to be invested with the power I gave them. The way I always meant them, they seem to have done more harm than good: it was my own meaning that gave me pause.

For me, those words implied something life-changing: “I am willing to sacrifice my happiness, and perhaps my life, for yours—myself for you.” That’s at least in part what my parents have clearly always meant when they’ve said the words to me and my sister. (They were also never shy about grand gestures [see “A wonderful gift”].) But this is clearly not what my friend means when he says the words to me.

So maybe those words shouldn’t have the power I gave them: “I love you but I’m not in love with you,” as another study put it. But, really, that’s not quite right either. Still, it’s clear that my mis-meaning of the words forced me to deny myself and my friends. And that hurt us, when the words themselves ought—by virtual of their meaning—to have done the opposite.

Why is “I love you” so scary? Denial? (Of what?)

I am trying, now, to tell my friends that I don’t merely tolerate their presence. It’s slow-going, though. The more I think about it, the greater the number of people I seem to need to tell: “You make me feel good, when you’re around, and I want you to know it because I want you to feel good too.” Once when I said the words, we even cried after.

Is such a response unmanly? Or is it normal? Or does this depend on the combination of the words, what they mean, and the broader cultural context that affords their power and possibilities? And then what, in that case, are the words themselves? (They’re not just information-carriers; they’re also units of shared-feeling.)

So what do you mean when you say these words? What does “I love you” mean to you? And why do you think that is? Let us know in the comments below.

To me, the words “I love you” have a different meaning each time I say them.

First of all, I don’t think love is ever the same, so how can the words ever have one meaning? The love I feel for someone is always unique; it is never exactly the same as the love I feel for someone else. Therefore “I love you” always carries a slightly different meaning.

I also feel their meaning depends on the context I would say them in, and to whom I would say them. I don’t recall having ever said “I love you” to my parents. It is just not something we really say out loud in my family (although we undoubtedly feel it), so saying it to them would feel heavy I guess. Though I say “I love you” to my friends all the time, so saying “I love you” to them is feels much easier. Also, if a friend would be dying and I would say “I love you” it carries way more than when I would say it when nothing life altering is going on.

It is quite a fascinating question!

Thanks for this Jeremy! Really could find myself in this and it is indeed a very interesting topic to think about.

😉