A wonderful gift

I was adopted. So was my mum. It’s very nearly a family tradition.

Both of us were chosen by our adoptive families, and afterward whisked away to a life of privilege. We were not abandoned. (That thought never occurred to me.) Instead, we were selected; special. I’ve always known this, perhaps because she tells me so at every opportunity.

“Special children have special things,” said my mum as she handed me an old-looking book. I had returned to Canada for the summer, after my first year as a tenure-track assistant professor in the Theory and History of Psychology Department, and she had just downsized from her suburban half-acre to a condo in downtown Toronto. Moving house always leads to discovered treasures. This book was certainly one of those.

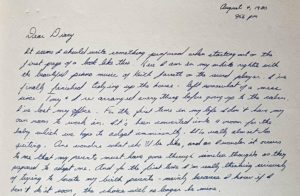

The book itself is beautiful: what you see in the picture above is reminiscent of what you often find on the inside cover of 19th century books. But it’s textured, not smooth. It feels almost woven. It’s quite the gift, especially for a bibliophile.

Opening it, I was quickly surprised by what I saw. This was not an ancient tome. The handwriting was obviously hers. And as I flipped through it, I saw the dated entries. Then I realized what she’d handed me: the book is her diary of my adoption.

Baby biographies are seldom seen today. The most famous was written by Charles Darwin: “A biographical sketch of an infant,” published in Mind in 1877. Perhaps because of his fame (he was not the first to publish such a thing), this article is often attributed with inaugurating “child study” as a scientific field. But that was also written decades after the fact. My mum’s diary was written in the moment. Many of the entries have both dates and times. It’s also quite a bit longer.

I am grateful, as I read her memories, that she didn’t inherit my grandfather’s pharmacist-scrawl. Or the chicken scratchings that I often encounter when I visit archives to do my research. My mum’s text is easily legible. It also contains all of the same sorts of surprises that I have come to expect from my historical scholarship. This is just a bit different, in no small part because it’s so personal.

On the first page, for example, I discovered that my mum—whom I love, and who I know loves me—didn’t want a little boy. She wanted a little girl. This entry is dated August 4th. That’s not quite a month after my birth. (We hadn’t met yet.) In other words, it’s clear that what I’ve been reading are her hopes for the future; uncensored and forgotten after nearly four decades.

Hopes and dreams provide a through-line that can be followed from start to finish. And these were jealously protected: an enclosure of no fewer than ten pages provided instructions for my nanny when we lived in England. (“No sweets,” she wrote, and breakfasts always to include “tuna, salmon, cheese, eggs… but no more than 3 or 4 eggs a week.”) By the last entry, too, it’s quite clear that she had forgotten her unmet daughter. That’s okay, though; eventually, I got a little sister anyway.

I doubt that my mum would have given me the book if she had re-read the first page. That’s not the sort of supportive and kindly thing that she typically says: “you weren’t what I wanted.” But I’m so grateful that she did give it to me. I’ve had the book for less than a month, now, and it’s already a treasured possession.

One of the things that adopted kids are often missing is a sense of personal history. Although I look very similar to both my parents, that was just a happy coincidence. It’s rare that the resemblance is so close. Most people would never even have guessed that I had been adopted. So my parents never needed to tell me what had happened. I’ve also since picked up their habits and mannerisms—both good and bad. I’m clearly their son. Still, though, I’m glad I’ve always known. I’m also glad, now, to have a history.

It’s good to be special. And it’s good to have special things. Thanks, mumsey!

Note: Photos and quotations used with permission.