Women’s empowerment in the context of microfinance services

Globally, women have less access to power than men do. This gender inequity can be seen in many aspects of daily life (Pratto & Walker, 2004). For example, 70% of the 759 million illiterate adults are female (United Nations, 2015) and 89% of all countries currently hold laws that limit women’s economic opportunities (World Bank Group, 2015). Importantly, the United Nations and governments around the world stress that empowering women is important to stimulate sustainable development (e.g., UN Women, 2018). One prominent way to improve women’s position and help them out of poverty is by offering women access to microfinance services (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). In my PhD project, supervised by Dr. Nina Hansen, Prof. Sabine Otten, and Prof. Robert Lensink, I examined women’s empowerment in the context of microfinance services (Huis, 2018). The key question was whether and how such services empower women. We focused on two main factors in women’s empowerment: the impact of (1) training adapted to the needs of female entrepreneurs (e.g., goal setting for businesses) and (2) women’s relationship with their husbands.

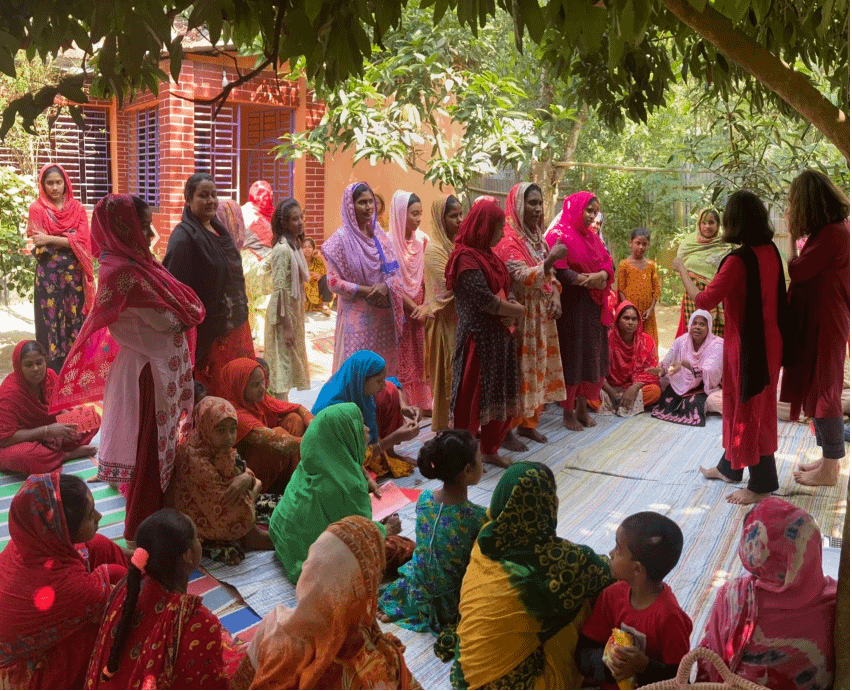

In 1983, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammud Yunus founded the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh to offer micro-loans to the rural poor. Today, many microfinance institutions offer small loans – $768 on average – to women. Most institutions also offer additional services such as saving groups or business training to support women in their income-generating activities, such as papaya cultivation or brick making. Women’s participation in microfinance services is expected to empower them. Yunus believes that (2006) if you empower women, you help families to get out of poverty faster than if you help them any other way. However, previous research reports mixed findings on this link: for example, women who receive microfinance services may feel more in control over their life, but they may also experience more intimate partner violence (for a theoretical review see Huis, Hansen, Otten, & Lensink, 2017). Husbands may inflict intimate partner violence because their wives spend less time on household responsibilities when they start running a business, or because husbands feel excluded from women-only programs (e.g., Allen et al., 2010; Rahman et al., 2009).

“Women who receive microfinance services may feel more in control over their life, but they may also experience more intimate partner violence.”

In my dissertation, my supervisors and I proposed the Three-Dimensional Model of Women’s Empowerment to integrate mixed findings from previous research and to better understand women’s empowerment in the field of microfinance services (Huis et al., 2017). This framework holds that women’s empowerment can take place on three distinct but related dimensions: personal beliefs and actions (personal empowerment), beliefs and actions in relation to relevant others (relational empowerment), and outcomes in the broader societal context (societal empowerment). We stress that one should differentiate between these three dimensions and add that time and culture are important factors to consider. For example, South Asian women are traditionally limited in their independent mobility (practice of female seclusion), whereas Sub-Saharan African women are traditionally more mobile and visible in the public domain (Heckert & Fabric, 2013). Thus, women’s ability to go to the market without an accompanying male relative may signal relational empowerment in South Asian countries but not in Sub-Saharan African countries.

Conducting research in Vietnam and Sri Lanka

We conducted our empirical research in Vietnam and Sri Lanka, two cultural contexts in Asia where people’s relationships with others strongly influence their sense of self. We hypothesized that women’s spousal relationship should be taken into account when investigating women’s empowerment. Indeed, a correlational study showed that female microfinance borrowers’ experience of intimate partner violence was related to having less influence on household decisions about expenditures that are traditionally not controlled by women (e.g., house repairs). We suggests that it is thus important to consider women’s relationship with their husbands in women’s empowerment.

“It is important to consider women’s relationship with their husbands in women’s empowerment.”

In two field research projects we systematically examined the impact of offering training addressing female microfinance borrowers’ needs and the impact of involving husbands in this training on women’s empowerment. In a large two-year longitudinal field experiment in Vietnam, we invited female microfinance borrowers (with or without their husbands) to a nine-month combined gender-and business-training program (GET-Ahead). We show that women who received access to this training showed improved personal and relational empowerment from before the training to one year after the training, compared to a group of female microfinance borrowers who were not invited to the training. Next, in Sri Lanka, we conducted focus group discussions to understand what training women need and whether they would like to participate with their spouse. We then invited female borrowers and their husbands together to one training session selected from the GET-Ahead training. The couples learned to set and share goals and responsibilities for their businesses. As one female participant stressed: ‘Then [I] don’t have to tell him what to do the whole time because [we] both have the knowledge and then it is easier to do work together.’ We showed that women learned to set smarter goals for their business in the training (e.g., buy more land and seeds to improve cultivation and sales of papaya). To understand whether couples’ joint participation in the training also influenced women’s empowerment, we asked couples to collaborate in a short subsequent decision-making task, which we videotaped. We coded couples’ non-verbal behavior and showed that women who participated in the training (compared to women who had not yet participated) show first signs of empowerment in interaction with their husbands (e.g., they were more likely to speak before their husbands spoke).

“After one year, women who received training showed improved personal and relational empowerment compared to a group of female microfinance borrowers who were not invited to the training.”

In my PhD project, I had the opportunity to meet many female microfinance entrepreneurs and learn how their life looks and what it means for them to become empowered. The results from our studies and the insights I gathered in conducting this research suggest that training female microfinance borrowers can empower them – if the training addresses what they need to learn. Additionally, I learned that it might be promising to involve women’s spouse so couples can learn to set and share responsibilities.

Note: Image from personal records of Marloes Huis. The image is also used for the cover of Marloes Huis’ Dissertation.

References

Armendáriz, B., & Morduch, J. (2010). The economics of microfinance (2nd Ed). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heckert, J., & Fabric, M.S. (2013). Improving data concerning women’s empowerment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 44(3), 319-344. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00360.x

Huis, M. A. (2018). Women’s empowerment in the context of microfinance services [Groningen]: University of Groningen. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/(…)4b-87b8-cb998108b6c0.

Huis, M. A., Hansen, N., Otten, S., & Lensink, R. (2017). A Three-Dimensional Model of Women’s Empowerment: Implications in the field of microfinance and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, [1678]. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01678

Pratto, F., & Walker, A. (2004). The bases of gendered power. In A. H. Eagly, A. Beall, & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The Psychology of Gender, 2nd edition (pp. 242-268). New York, US: Guilford Publications.

United Nations (2015). World’s Women 2015: Trends and Statistics. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. Retrieved from http://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/downloads/WorldsWomen2015_report.pdf

UN Women (2018). Turning promises into action: Gender equality in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from http://www.unwomen.org//media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/p

blications/2018/sdg-report-gender-equality-in-the-2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development-2018-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5653