Welcome to hotel California! You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave…

This blog post is a short reflection on a recent theoretical paper on abusive supervision written by Barbara Wisse with Kimberley Breevaart and Birgit Schyns.

Working life is not always easy. Although employment comes with many advantages, sometimes it seems that the negative aspects overshadow the positive ones. One person who seems to be able to ‘make or break’ people’s job experiences is their boss. Sure, many bosses are great: they motivate, cooperate, facilitate, communicate, and have many admirable qualities. But not all bosses are great. In fact, some are horrible. Indeed, sometimes people have to deal with a boss who manipulates, humiliates, ostracizes, lies, or displays other nasty behaviors. It is bad enough if supervisors act like this every now and then (for instance, during a particularly stressful day), but it becomes even more problematic if this is recurring behavior. If that is the case, we talk of abusive supervision.

Abusive supervision leads to reduced well-being, and its consequences range from anxiety and depression to problem drinking and insomnia. Subordinates with abusive supervisors often suffer for a long time. “Suffer for a long time?”, I hear you think, “That is probably a mistake. Surely if people have an abusive boss they simply move on and leave the abusive relationship with their supervisor!” Well, no. Just like how battered women often find it difficult to escape an abusive relationship, battered employees may also find that it’s not so easy to get away. How can that be possible?

Abusive supervision leads to reduced well-being, and its consequences range from anxiety and depression to problem drinking and insomnia.

The Barriers Model

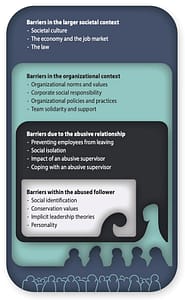

Based on considerations around battered women, Kimberley Breevaart, Birgit Schyns and myself identified several layers of barriers that hinder employees from escaping their abusive supervisor. Each layer represents increasingly narrow categories of barriers that prevent employees from sending in their notice. The broadest layer (Layer 1) concerns barriers in the larger societal context. For instance, if there is no societal awareness about the problem, it is more difficult for victims of abuse to be taken seriously and to find support. Without being listened to and without some help, ending abuse becomes more difficult (just think about what the #metoo movement did for victims of sexual harassment). Of course, if people simply do not see any opportunities for finding employment elsewhere, leaving also becomes more difficult (for instance, during a recession or a global pandemic).

Next, there are barriers in the organizational context (Layer 2). Organizational norms (like those that are more bureaucratic, political, or masculine in nature) may foster sustained abuse or may be more accepting of abuse than others. Additionally, organizational policies may be unclear or unsupportive. For instance, an abused employee might not feel safe to report issues for fear of the complaint backfiring and the supervisor retaliating. Employees may also find it difficult to leave because of feelings of solidarity. One of my bests friends is a person I met at work (my office mate) while we were both struggling with an abusive supervisor. I would not have liked to “abandon” my friend at that time, and I’m sure he would state the same.

Then, the abusive supervisor him- or herself can constitute a third barrier (Layer 3) for instance by simply preventing the employee from leaving. Supervisors may refuse providing victims with good references that help them to find another employment, or they may constantly tackle any attempts at promotion (claiming that the abused employee is not yet meeting requirements for promotion). Also, having to deal with abuse can stress a person out, taking all their energy. Employees’ drained resources may cause them to be too depleted to take the actions that are required for stopping the abuse (for instance: looking for other jobs, alerting HR, etc.). Also, continued abuse may lead abused employees to think they are incompetent and will not be able to find another employment.

Finally, the employee’s own thoughts and feelings might pose a barrier to resigning (Layer 4). For instance, they may believe they need to adhere to the expectations that society, parents or friends may have of them (don’t be a quitter; don’t be a cry-baby). As long as the social norm is to stay in an abusive supervisory relationship, especially the more agreeable and conscientious employees will adhere to that norm.

Clearly, there are plenty of reasons why it is so difficult to leave an abusive relationship. In this blog post you only find a couple of examples, but there are many more. Moreover, victims of workplace abuse can experience more than just one of those barriers. What we hoped to make clear with our model, however, is that the prolonged nature of abusive supervision cannot be understood within the limits of supervisor-subordinate dynamics alone, but instead involves societal, organizational, dyadic, and intra-individual factors that should all be taken into account. Outlining such factors is important, as it may help to prevent victim blaming: not all factors are under the victim’s own control.

The prolonged nature of abusive supervision cannot be understood within the limits of supervisor-subordinate dynamics alone

Moving towards interventions

If we acknowledge that factors explaining prolonged abuse can be found outside the limits of supervisor-subordinate dynamics, this may also facilitate the development of interventions aimed at helping abused employees. That is, interventions may also include societal and organizational factors (next to dyadic and intra-individual ones). It may be difficult to address problems related to the economy and the job market, but one powerful way to break down barriers on the broadest, societal level may be through creating societal awareness (e.g., a movement such as #metoo). Another powerful way to protect employees against workplace abuse is by adopting (and enforcing) appropriate laws. Organizations also play a crucial role in creating a support system for those who fall victim to abusive supervision, and in making sure that victims have access to key resources (e.g., information, support from colleagues, the instalment of an Ombudsperson). Apart from having clear rules, organizations should actively try to put an end to abusive behavior by confronting abusive leaders with negative consequences of their behavior. If a supervisor is found to be abusive, they should ideally be removed from responsibility over others. Moreover, organizational interventions also have an important signaling function, increasing the likelihood that employees will confront the issue, report to higher management or engage in external whistleblowing. Colleagues of an abused employee can also help the victim.

Thus, instead of acting as if it is the victim’s sole responsibility to end the abuse (and blaming them for not doing so), it would be more helpful to view abuse from a systemic perspective. Why not all ask the question: what can we (as a society, as an organization, as a colleague, an HR-professional, a confidential advisor) do to help an abused employee escape the abuse? Working with an abusive boss should not feel like being stuck in hotel California.

Read about the Barriers model here:

Breevaart, K., Wisse, B., Schyns, B. (in press). Trapped at work: The Barriers Model of Abusive Supervision. Academy of Management Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2021.0007

Image credits: photo by Jobs for Felons Hub; licensed under CC BY 2.0. Barriers Model image by Boudewijn Wisse.