Understanding interpersonal relationships: the key to social interactions

We are social animals, whether we like it or not. Due to our social nature, understanding our interactions with other people, i.e., our interpersonal style, is key to understanding ourselves. Interpersonal styles encompass the skills, behaviours, and tactics we use to interact with others effectively – how we read intentions, make interpretations, and respond. Carson (1969, p.25) noted that interpersonal relationships affect our lives both during interactions and outside them, i.e. through imagined interactions. This is an important postulate because as Horowitz and Strack (2011) mention, “errors in social perception can lead to […] miscommunications and social misfires” (p.4.), and ultimately to larger problems. I became aware of interpersonal styles during my first-year course on Personality and Individual Differences, by Dr. Bertus Jeronimus, and wish to share my fascination with this psychological treasure.

“Due to our social nature, understanding our interactions with other people, i.e., our interpersonal style, is key to understanding ourselves”

Similar to the imagined interactions, Charles Cooley’s theory of the “looking-glass self” proposes that how we imagine others perceive and evaluate us affects our sense of self and our interactions. The American sociologist’s theory came to life during the Weekend of Science (Weekend van de Wetenschap, 05-10-2019). Dr. Marije aan het Rot and I invited visitors to complete the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) and discuss interpersonal styles. Most notable was a young couple’s interactive game that put Cooley’s theory to practice; they tried to construct each other’s interpersonal style by answering the IIP items on each other’s behalf, then compared it to the results of their own separate run. Naturally, the view they had of themselves differed from the other’s view, and their discussion prompted me to reflect on how the theory partially helps us understand why social interactions are important to us: other people’s opinions of us matter to our sense of self, therefore healthy interpersonal interactions are essential.

“During the Weekend of Science, Dr. Marije aan het Rot and I invited visitors to (…) discuss interpersonal styles”

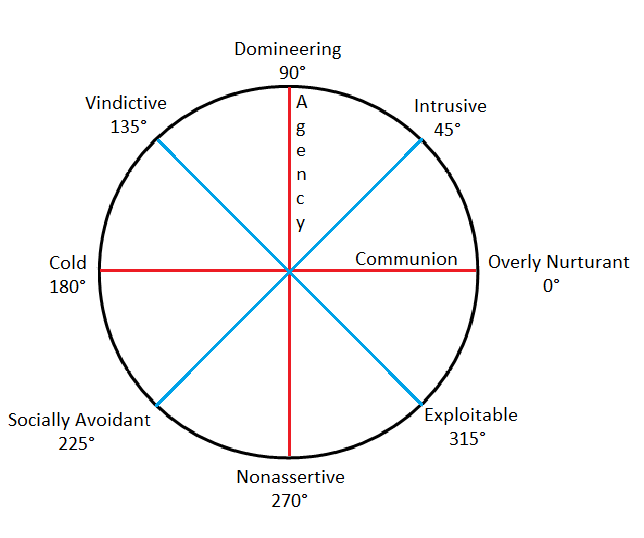

Each interpersonal style’s uniqueness makes it impossible to encapsulate all individual differences in one personality test. The Society for Interpersonal Theory and Research (SITAR) has since 1997 helped maintain coherence and unity in the interpersonal domain. In particular, Harry Stack Sullivan (1892-1949) advanced interpersonal relationships as crucial for the development of a healthy and adaptive personality (Fournier, Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2011). Sullivan’s theories “radically transformed psychoanalysis […] from the study of things and events that occur within an individual, to the study of interpersonal things’’ (Evans, 1996). Inspired by Sullivan, Mervin Freedman and Timothy Leary and colleagues (1951) created the Interpersonal Circumplex Model (ICM) to describe social interaction, with agency and communion as the main dimensions. Respectively, these represent the extent of independence and closeness an individual exhibits in their interpersonal interactions (Wiggins, 1987). In turn, Jerry Wiggins, Leonard Horowitz, and many others took the ICM as inspiration for their own contributions, set to carve out salient individual differences in interpersonal styles.

“Each interpersonal style’s uniqueness makes it impossible to encapsulate all individual differences in one personality test.”

Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus (2000) developed the 127-item IIP, with items divided into behaviours one “does too much” and that are “too hard to do”. Their design was based on the ICM, and it is mostly used for clinical purposes, where respondents indicate how distressed they are by said behaviours. The octants and two main dimensions of the IIP are statistically and conceptually related to one another, with categories at polar ends being negatively correlated, and the adjacent categories being positively correlated (see Figure 1). It has been argued that “all forms of social behaviour can […] be viewed as combinations of the four poles” (e.g., Fournier, Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2011), and if this can be empirically supported, then we could learn a lot about social dynamics.

Figure 1: an adapted version of the ICM showing the two main dimensions (red lines) and the octants (blue and red lines)

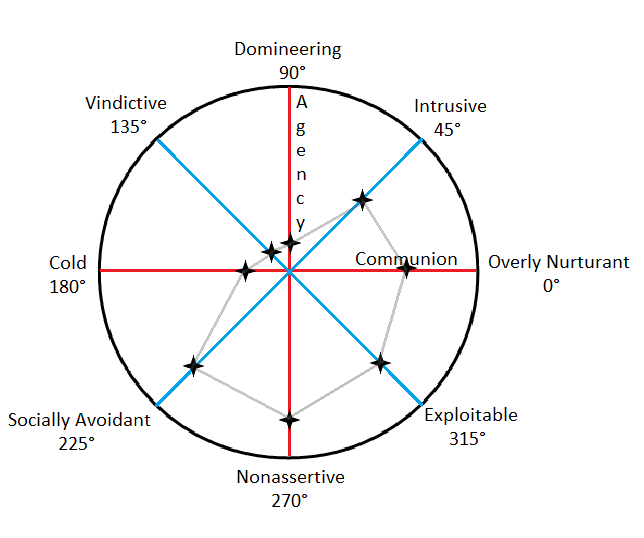

Interpersonal questionnaires will never generate “right” or “wrong” answers, because a specific score is no less desirable than another. All variations in personality and interpersonal styles have their specific niche in which they outperform others, making each of them desirable/adaptive depending on the context. Once somebody’s interpersonal characteristics are understood, the person-environment fit (Roberts&Robins, 2004) can be used to help integrate individuals in their optimal environment. This captures the beauty of personality psychology, where each individual is intrinsically valuable. For example, if an individual ‘Sergio’ completed the IIP and his result is illustrated in Figure 2, we could infer his nurturant and possibly introverted nature, as well as that he does not assert himself often and that he is not confrontational. Sergio’s personality will help him in certain situations, but he can be taken advantage of in others.

Figure 2: A fictional example of an IIP result

Finally, studying interpersonal styles has advantages in several academic areas, as they are the driving factor behind various fundamental interactions. Interpersonal traits have been associated with differences in academic achievement (e.g., Melzer & Grant, 2016), status (e.g., Cundiff ea, 2011), health (e.g., Chapman ea, 2019) and well-being (e.g., Li ea, 2017). These findings fit with the idea that interpersonal styles are an important part to understand in our social machinations, and the key to an adaptive and fulfilled life.

References

Carson, R. C. (1969). Interaction concepts of personality. Aldine Publishing Co.

Chapman, B. P., Elliot, A., Sutin, A., Terraciano, A., Zelinski, E., Schaie, W., … & Hofer, S. (2019). Mortality Risk Associated With Personality Facets of the Big Five and Interpersonal Circumplex Across Three Aging Cohorts. Psychosomatic medicine.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner’.

Cundiff, J. M., Smith, T. W., Uchino, B. N., & Berg, C. A. (2011). An interpersonal analysis of subjective social status and psychosocial risk. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 47–74.

Evans, F. B., III. (1996). Harry Stack Sullivan: Interpersonal theory and psychotherapy. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

Fournier, M., Moskowitz, D. and Zuroff, D. (2011). Origins and Applications of the Interpersonal Circumplex. In: L. Horowitz and S. Strack, ed., Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Freedman, M. B., Leary, T. F., Ossorio, A. G., & Goffey, H. S. (1951). The Interpersonal Dimension of Personality 1. Journal of personality, 20(2), 143-161.

Horowitz, L. and Strack, S. (2011). Introduction. In: L. Horowitz and S. Strack, ed., Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p.5.

Li, P.-H., Chu, L.-H., & Yu, M.-N. (2017). Joy share with others is more joyful: Interpersonal relationship as a mediator between optimistic explanatory style and well-being. Chinese Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 49, 53–77.

Melzer, D. K., & Grant, R. M. (2016). Investigating differences in personality traits and academic needs among prepared and underprepared first-year college students. Journal of College Student Development, 57(1), 99–103.

Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2013). Interpersonal theory of personality. In H. Tennen, J. Suls, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Personality and social psychology (p. 141–159). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Person-environment fit and its implications for personality development: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality, 72(1), 89–110.

Wiggins, J. (1987). Agency and Communion as Conceptual Coordinates for the Understanding and Measurement of Interpersonal Behavior. In D. Cicchetti & W. Grove, Thinking Clearly about Psychology : Personality and Psychopathology, Vol. 2 (p. 89). Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Note

Iimage by Antonella B, licenced under CC BY 2.0.

Great topic! Thank you for writing this article. I feel like this is a promising direction that we should devote more resources into.

The topic is aligned with some contemporary movements that I observe in the field. In Germany, for example, psychodynamic and behavioural therapies are covered by the health insurance. Recently, however, systemic therapies have provided sufficient evidence to be included in health insurance coverance.

We are shifting from seeing the individual’s intrapersonal world, which is an isolated and somewhat sterile way, to acknowledging that every client is embedded in a complex social situation.

Further pursuing research on interpersonal styles could have significant impacts in various domains. How exciting!