There is life after retirement

Throughout my career I pursued research questions which required funding and took decades to answer. As a victim of compulsory retirement, this type of research was no longer feasible for me. But research is too much fun to stop doing, merely because age discrimination is rampant in this country. I finally found time to address questions that had interested me for decades and to pursue any topic that pricked my curiosity. I also discovered that one does not always need a laboratory and PhD students or PostDocs to study interesting issues.

For obvious reasons, one of the topics that had interested me was the relationship between age and scientific productivity. Was it really true, as the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) still believes, that innovation only comes from the young? As it turned out, it was not. While Einstein was only 26 years old when he published his Nobel Prize-winning articles, more recent laureates in physics conducted their research at an average age of 50 years. Moreover, active researchers show no decline in productivity or impact even at 70. I published two articles on this (Stroebe, 2010, 2016a), but have not managed to reduce ageism (yet).

“Was it really true, as the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) still believes, that innovation only comes from the young?”

Another topic that had long interested me was the association between the availability of firearms and homicide. Whenever I lectured on aggression, I causally related the 300 million guns owned by Americans to their high homicide rate. My argument was often countered by students, who asked me to explain why the Swiss had one of the lowest homicide rates in the world, even though they are number 3 in world gun ownership. When I started reading the gun literature after my retirement, I realized that the answer to the question was so trivial, it should have occurred to me long ago. Guns are means and not goals. People rarely kill someone to try out their new gun. But guns are more deadly than any other killing means. Therefore people who want to kill someone (or themselves) find doing so much easier if they live in the States or Switzerland rather than in the Netherlands or Germany. The low Swiss homicide rate indicates that there are fewer people in Switzerland than in the USA intent on committing homicides. But if the Swiss do murder, their preferred means are guns.

“Guns are means and not goals. People rarely kill someone to try out their new gun. But guns are more deadly than any other killing means.”

But if guns are such an effective means of killing others or oneself, should measures of gun control not be the answer? They certainly would, if effective measures could be introduced. However, since Americans have the constitutional right to own guns, these measures can only control new gun sales. With 300 million guns already circulating, no federal registration system, and private gun sales allowed, new gun control measures would be as effective in controlling guns as closing one hole in a sieve is in preventing the leakage of water. I have written articles on this topic (Stroebe, 2013, 2015, in press) with so little impact that I have not even been attacked by the United States National Rifle Association.

My interest in scientific fraud was aroused by the Stapel case. I spent weeks searching the internet for other fraud cases, simply out of curiosity. I was not only struck by the frequency of such cases but also by the fact that practically none was discovered by journal reviewers or editors. This led me (jointly with Tom Postmes and Russell Spears) to write an article on the myth of self-correction in science (Stroebe, Postmes & Spears, 2012). It appeared just before the publication of the Levelt Report that based part their critique on the fact that the fraud had not been discovered by journal reviewers. Our article was used by the European Association of Social Psychology to argue that the attack on social psychology by Pim Levelt and colleagues was “unacceptably flawed”.

“Our article was used to argue that the attack on social psychology by Pim Levelt and colleagues was “unacceptably flawed”.”

A final example of how the freedom to indulge one’s curiosity can be rewarding is my recent article on the validity of student ratings of teaching (Stroebe, 2016b, in press). A colleague had sent me a paper that linked students’ course evaluations not only to the grades they received in the evaluated courses, but also to the grades they received in follow-up courses that built on the knowledge of the rated course (Braga et al., 2014). Unexpectedly, while the evaluations were positively correlated with students’ grades within the same course, they were negatively correlated with students’ grades in later courses. The authors concluded that (at least less able) students prefer courses that require little work and result in good grades, even though they do not necessarily add much in terms of acquisition of knowledge. I found this so interesting that I read up on it and wrote an article documenting the various psychological processes responsible for this effect. In line with Braga and colleagues, I concluded that student ratings of teaching reflect course enjoyment rather than learning.

“Unexpectedly, while the evaluations were positively correlated with students’ grades within the same course, they were negatively correlated with students’ grades in later courses.”

To conclude, if I had not been forced to retire, I would still be working full time and conducting empirical research. But retirement has provided me with time to pursue any topic that arouses my interest. Doing so has strengthened my belief that analyzing interesting issues from a social-psychology perspective provides insights that other disciplines fail to offer. While I have enjoyed doing this, I still miss the excitement of collecting empirical data to test theoretical hypotheses.

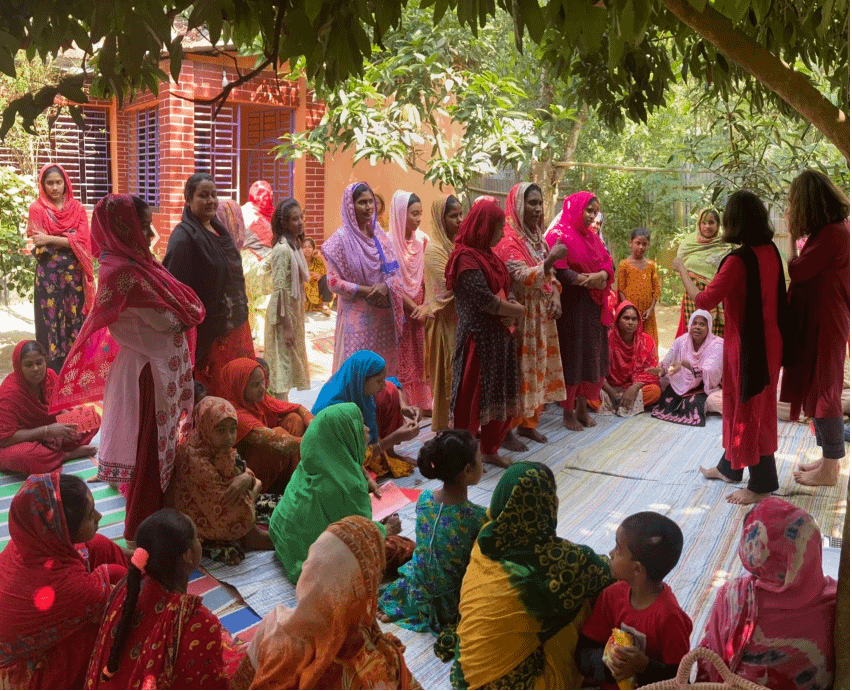

NOTE: Picture by Margaret Stroebe

References

Braga, M., Paccagnella, M. & Pellizzari, M. (2014). Evaluating students’ evaluations of professors. Economics of Education Review, 41, 71-88.

Stroebe, W., (2010). The graying of academia: Will it reduce scientific productivity? American Psychologist, 65, 660-673.

Stroebe, W., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2012) Scientific misconduct and the myth of self-correction in science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 670-688

Stroebe, W. (2013). Firearm possession and violent death: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 209-721.

Stroebe, W. (2015). Waffenbesitz in den USA: Gutes Recht oder böser Fluch. Gehirn & Geist, 2, 16-20.

Stroebe, W. (2016a). The key to productivity is not age but ability and motivation. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/search?f[0]=field_breaking_news_byline%3A131956&f[1]=field_breaking_news_byline%3A131957

Stroebe, W. (2016b). Student evaluation of teaching: No measure for the TEF. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/comment/student-evaluations-teaching-no-measure-tef

Stroebe, W. (in press). Firearm availability and violent death: The need for a culture change in attitudes toward guns. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy.

Stroebe, W. (in press). Why good teaching evaluations may reward bad teaching: On grade inflation and other unintended consequences of student evaluations. Perspectives on Psychological Science.