Strong emotion sharing and blurred work-life boundaries: A dangerous mix for young healthcare professionals

Working in healthcare can be emotionally draining even under normal circumstances. Dealing with patients and their families, often under time pressure, experiencing patients’ suffering, and the sense that sometimes nothing can be done can challenge healthcare workers’ sense of control and well-being. What might be a challenge under normal circumstances, can become a seemingly unsurmountable problem in times of crisis. It is easy to imagine the emotional demands that healthcare workers face in their work rising exponentially during the current Corona pandemic. In the media, healthcare workers all over the world describe scenes of chaos due to an overwhelming number of patients, unclear guidelines, lack of protective equipment and a shortage of testing material. In the midst of chaos, healthcare workers see patients and their families struggle and ‘feel their pain’.1 This often gives them the necessary motivation to keep doing their important work. Yet, it likely leaves them emotionally drained at the end of the day as well.

In times like this, individual differences in the ability to maintain well-being despite heightened emotional demands at work, and the struggle to do so, will become more visible than during normal times. Research findings on aging in the workplace point towards employees’ age as a factor that matters for workplace well-being during the Corona pandemic. Younger healthcare workers (in their 20s and 30s) may be less at risk to catch the Corona virus than their older coworkers (in their 50s and 60s). Yet, notwithstanding the risk of getting the virus itself, there are at least two reasons why being an older healthcare worker may actually pose an advantage in times like this. These two reasons lie in the different ways in which younger and older workers experience empathy, and in their boundary setting behavior between work and private life. These tendencies could create a dangerous mix for young healthcare professionals in times of crisis – but protect the older ones.

Individual differences in the ability to maintain well-being despite heightened emotional demands at work will become more visible than during normal times.

The dangers of empathy

Empathy is a double-edged sword in the life of healthcare workers. It is an important motivator to provide care. Yet, empathy also involves sharing others’ emotions. This can easily get overwhelming if emotions are negative and intense, and if such emotions keep coming in high frequency. Working in a hospital or care facility these days certainly evokes many moments of intense feelings of anxiety, sadness, and even anger in patients, their families, and other coworkers. Even small differences in empathy can therefore make a big difference for well-being. In a recent study, we found that emotionally demanding jobs (of which health care is a prime example) enlarged age differences in empathy (Wieck, Kunzmann, & Scheibe, in press). We measured empathy by having our participants watch film clips of working adults describing emotional events from their work, such as being unfairly treated by the supervisor, witnessing a clients’ heart attack during a meeting, or seeing a student making a lot of progress. The participants’ task was to judge both the film protagonists’ and their own feelings while listening to these stories, and to rate the sympathy that they feel. We found that younger participants were better than older participants in recognizing others’ emotions, while older participants experienced more sympathy, this warm and hearty feeling towards the other person. Strikingly, those younger participants who were working in emotionally demanding jobs further displayed elevated levels of emotion sharing when comparing them to their older counterparts. What does this mean? Being an ‘emotion sharer’ may draw people into emotionally demanding jobs when first choosing a career, but it may be difficult to keep up over the course of the career. In fact, we believe older healthcare workers develop a ‘healthy distancing response’: They recognize their patients’ pain, they feel high levels of sympathy, but do not necessarily “share the pain”. Less emotion sharing comes down to a lower burden for well-being. Older healthcare workers may have learned over the years that they can be more effective if they maintain a healthy emotional distance towards their patients and others with whom they interact at work.

Being an ‘emotion sharer’ may draw people into emotionally demanding jobs when first choosing a career, but it may be difficult to keep up over the course of the career.

Maintaining a work-life balance

The second reason why younger healthcare workers may be more at risk than their older coworkers when emotional job demands run high, lies in the way people navigate between work and private life spheres. Research in organizational psychology shows that, for most of us, maintaining strong boundaries between work and private life is a successful strategy to protect both our well-being and our effectiveness. In a two-study project, we discovered that older employees were more likely to set strong boundaries than younger employees, and as a result, experienced higher levels of work-life balance (Spieler, Scheibe, & Stamov-Rossnagel, 2018). Boundaries can be set around work and nonwork life spheres. During work periods, strong boundaries mean switching off private life in thoughts and actions: Not ruminating about the tense conversation with the partner last night, not using social media to make plans for the weekend. During nonwork periods, strong boundaries mean switching off from work: Ignoring work-related calls, spending time socializing and unwinding rather than ruminating about the workday’s events. Keeping strong boundaries has many benefits. It helps us to focus on our work when at work, and to unwind, relax and sleep during our leisure time – thus regaining energy to face the next day’s demands. Older employees may have learned about these benefits as they grew older. In our two studies, we discovered that through their boundary management, older employees enjoyed higher work-life balance than younger employees. Not because their lives were less stressful (which we ruled out by asking about care taking demands at home and characteristics of their job), but because they had developed a habit to keep work and private life more clearly apart from each other.

As long as they don’t catch the virus, older healthcare workers probably are well equipped to face the emotional challenges of their work.

Watch out for younger staff

When we think about older age in times of Corona, our first thought often is that older people are at high risk to catch the virus. This may be true, but let’s not underestimate the benefits of age in the work context. With age comes wisdom, as the saying goes. As long as they don’t catch the virus, older healthcare workers probably are well equipped to face the emotional challenges of their work: Not letting patients’ pain get under their skin and maintaining strong boundaries between work and leisure periods – both being smart ways to protect well-being when emotional job demands are on the rise. Rather, hospitals and care facilities are well advised to watch out for their younger staff who may run a higher risk for exhaustion, the longer this crisis endures.

1 For media reports from inside hospitals and care facilities, see for example here and here.

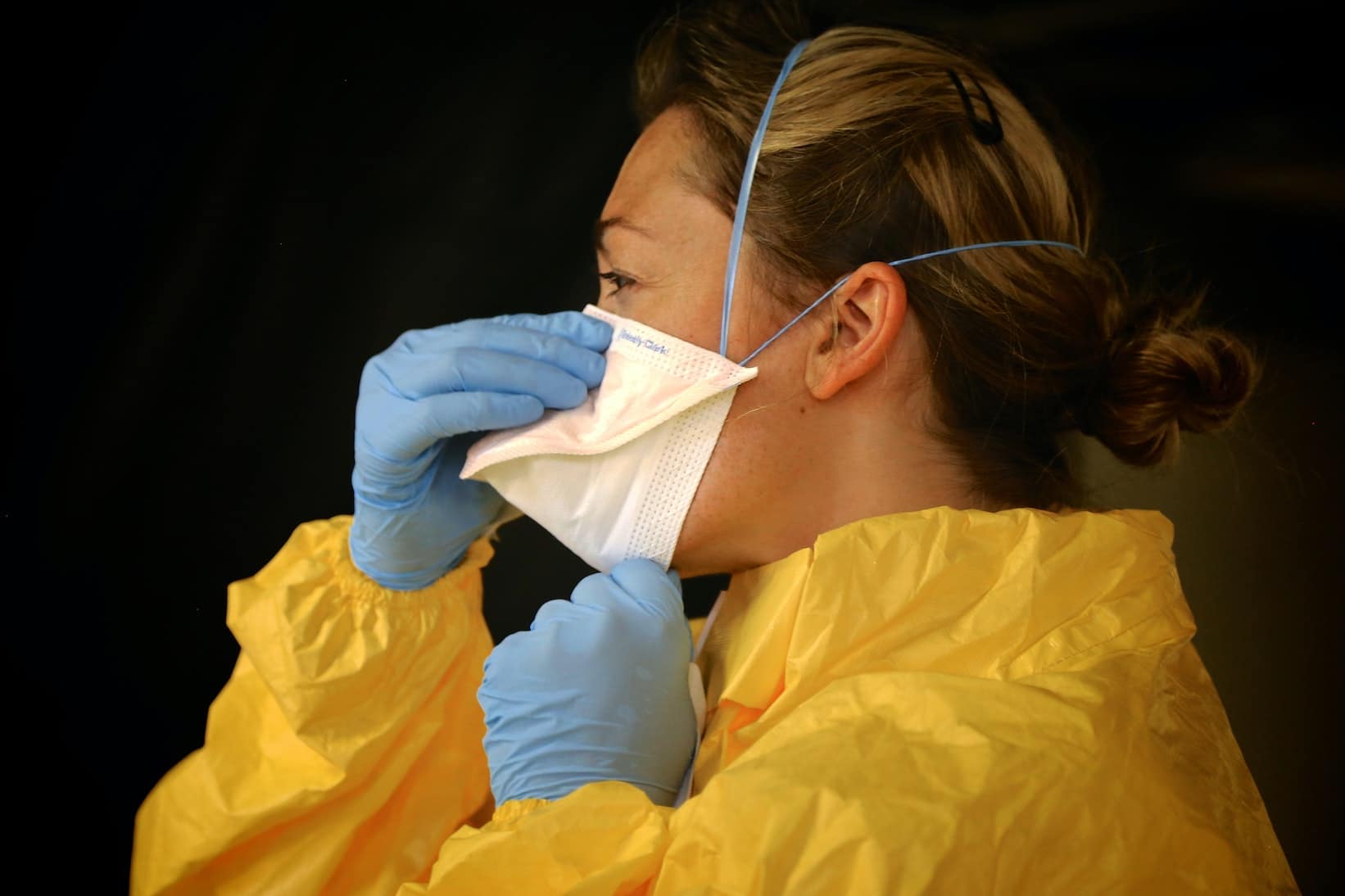

Image credit: Photo by CDC on Pexels.

References

Spieler, I., Scheibe, S., & Stamov-Roßnagel, C. (2018). Keeping work and private life apart: Age-related differences in managing the work–nonwork interface. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39, 1233-1251. doi:10.1002/job.2283.

Wieck, C., Kunzmann, U., & Scheibe, S. (in press). Empathy at work: The role of age and emotional job demands. Psychology and Aging. doi: 10.1037/pag0000469.

Hi Susanne, thanks for this interesting piece! Reading your article, I found myself wondering whether we know anything about the ways in which older workers actively transfer their emotion-relevant skills to their younger coworkers, and whether these younger coworkers are actually open to learning from their older counterparts. Is there any research on such ‘intergenerational learning’?

Hi Eric, interesting question, thank you! There is some work on knowledge sharing between age-diverse coworkers, but to my knowledge, this work has not distinguished what type of knowledge is shared (i.e. is it task-related or socio-emotional knowledge, which would include emotion-relevant skills). The research on knowledge sharing suggests that both parties — the younger and the older coworkers — benefit as knowledge sharing meets their needs for relatedness and competence. Whether younger coworkers are open to learning about self-regulation from their older coworkers is probably a question of age stereotypes. If younger folks hold more negative age stereotypes, they will probably less open to listen to their older colleagues.