Solving the Cultural Paradox of Loneliness

Are members of individualistic cultures more likely to feel lonely than members of collectivistic cultures?

Intuitively, one would expect that the answer is yes. After all, in individualistic societies, more people live alone, get divorced, make their own, independent decisions, often hardly (if at all) know their neighbours, and sometimes abandon family life altogether. However, although these characteristics seem to have the potential to increase loneliness, average loneliness tends to be lower in more individualistic than in more collectivistic cultures (e.g., Lykes & Kemmelmeier, 2014).

This contradiction, which we call the “cultural paradox of loneliness”, was the starting point for our research about cultural norms and loneliness. Five years later, and after conducting research in 18 different countries, we believe to have found an explanation (Heu et al., 2020).

“Spending more time alone or having less relationships can increase loneliness, but does not necessarily do so.”

In principle, the solution to the cultural paradox of loneliness is quite simple, and something you probably know from your own experience: Spending more time alone or having less relationships can increase loneliness, but does not necessarily do so. At the same time, there are numerous other reasons for feeling lonely: You can feel different from your friends, you may just have had an argument with your partner, your parents may not have been sufficiently affectionate in your childhood, you may realize that there is no one who can truly share your individual experiences, problems, etc. (e.g., Moustakas, 1972; Perlman & Peplau, 1981; Rokach, 1989). That is, just as Dutch singer-songwriter Anouk sings, you can be “alone together, all alone, together all alone”.

As such, it is possible that the risks for loneliness that living in an individualistic culture entails (more time alone, fewer stable social relations) are simply outweighed by the risks implied by higher collectivism. But what are these risks implied by higher collectivism?

To answer this question, it is important to understand that different cultures contain different social norms. Social norms are unwritten rules about what is commonly done, or what should [not] be done, that steer our behaviour and thinking (Chiu et al., 2010). In some cultures, it is, for example, normal to move out of your parents’ home after high school; in others, it is normal to stay with them until you get married. In some cultures, it is uncommon not to have romantic relationships before marriage (if you get married at all); in other cultures, having such relationships is unacceptable. Social norms exist in many areas of life, but, when trying to better understand loneliness, norms about social relationships (as in the examples above) are particularly relevant. This is because they can influence important risk and protective factors for loneliness:

“When trying to understand loneliness, norms about social relationships are particularly relevant.”

For one, they steer how we relate to each other (e.g., whether we establish romantic relationships; how much we talk about our emotions with our friends; how often we see our parents), which can influence the quantity and quality of our relationships, and how well our relational needs are fulfilled (e.g., whether we feel like we belong; whether we can turn to someone for advice; Weiss, 1974). In turn, better or more fulfilling relationships tend to protect from loneliness.

Second, cultural norms about social relationships define the standards that we compare our relationships to (e.g., whether we believe that it is essential to have a romantic partner; whether we consider it important that we can talk about our emotions to friends). If our expectations from relationships are higher than what our own relationships can offer, we perceive them as dissatisfying – and being dissatisfied with our relationships can make us feel lonely (Heu et al., 2019; Perlman & Peplau, 1981).

Although there are social norms about relationships in all cultures, there are often more, more demanding and stricter norms about social relationships in more collectivistic than in more individualistic cultures (Heu et al., 2020). This is important because more such “restrictiveness” is a double-edged sword for loneliness:

On the one hand, more restrictive norms motivate people to maintain their existing social relationships and to spend time with others. Therefore, in more collectivistic cultures, less people will end up truly isolated or with few social interactions, and this will protect some people from feeling lonely. On the other hand, more restrictive norms can also limit people’s freedom of selecting relationships that they themselves consider fulfilling. They can often not leave dissatisfying or even abusive relationships and/or establish new, better relationships. Also, more restrictive norms can create higher and more rigid expectations. Consequently, all those who can – for whichever reason – not live up to such expectations may become dissatisfied with their relationships or may experience social sanctions such as exclusion. For instance, having sex before marriage can, in some cultures, lead to exclusion from the family. In sum, the risks for loneliness that more collectivistic cultures pose may then lead to higher average loneliness.

“Our research implies that interventions that are effective in one cultural group can be less effective in others”

As such, our findings and theorizing suggest that neither culture can protect all its members from feeling lonely. Different cultural norms simply in- or decrease distinct risks for loneliness. This is practically relevant because it implies that interventions that are effective in one cultural group can be less effective in others: While interventions that reduce social isolation (e.g., community meals) may be promising in more individualistic cultures, they may often hardly reduce the loneliness of those who live in more collectivistic cultures with strong family ties. Indeed, in more collectivistic cultures, people may profit more from interventions that address the lack of someone to openly talk to or the stigma associated with being different. By linking cultural norms to different risks, our explanation for the cultural paradox of loneliness hence provides starting points for culture-sensitive interventions.

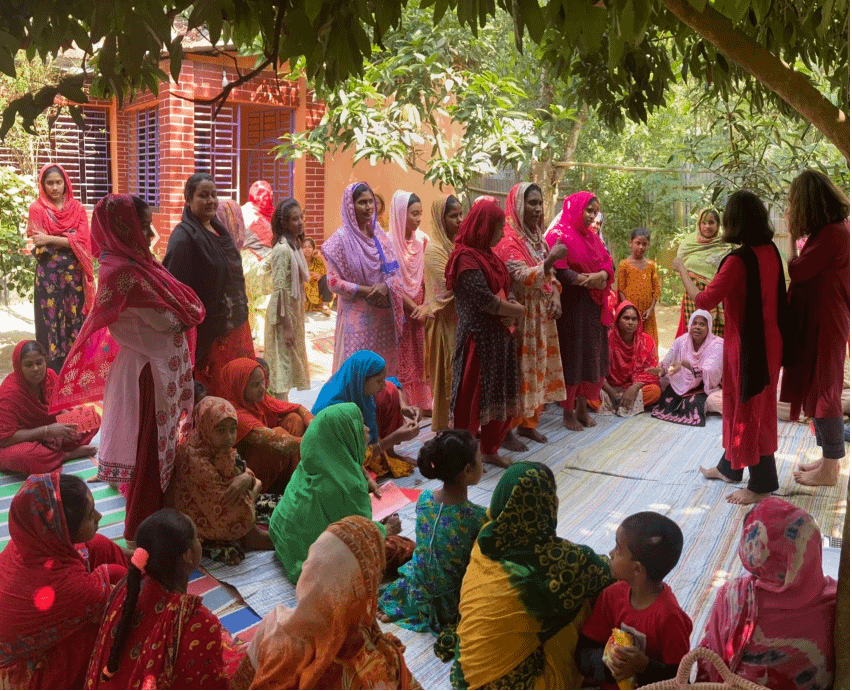

Note. Picture taken in Bangalore, India by Luzia Heu.

This blog post is based on the following articles:

Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M., & Hansen, N. (2020). Does Loneliness Thrive in Relational Freedom or Restriction? The Culture-Loneliness Framework. Review of General Psychology, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268020959033

Heu, L. C. (2020). Solving the Cultural Paradox of Loneliness (Doctoral dissertation). University of Groningen.

Other references:

Chiu, C. Y., Gelfand, M. J., Yamagishi, T., Shteynberg, G., Wan, C. (2010). Intersubjective culture: The role of intersubjective perceptions in cross-cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375562

Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M., & Hansen, N. Lonely Alone or Lonely Together? A Cultural-Psychological Examination of Individualism-Collectivism and Loneliness in Five European Countries (2019). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(5), 780-793. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0146167218796793

Lykes, V. A., Kemmelmeier, M. (2014). What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(3), 468–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113509881

Moustakas, C. E. (1972). Loneliness and love. Prentice Hall.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness. In R. Gilmour, & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal Relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder (pp. 31-56). Academic Press.

Rokach, A. (1989). Antecedents of loneliness: A factorial analysis. The Journal of Psychology, 123(4), 369-384. doi:10.1080/00223980.1989.10542992

Weiss, R. S. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others: joining, molding, conforming, helping, loving (pp.17-26). Prentice Hall.