Notes on synchrony:

when science and art collide

A text inspired by Notes on Synchrony, a collaborative project between dancers and neuroscientists in which art and science merge. Notes on Synchrony will be on in the Groningen Grand Theatre as part of the Moving Futures festival on the 16th and 17th of March.

Which of the following words do you associate with art, and which ones with science? Experiment, question, knowledge, exploration, creativity, failure, measurement, precision, dedication, passion, effort, meaning, humanity.

Most people imagine art and science as fundamentally different. On the one hand, there is the systematic and methodical world of science, inhabited by specimens of outstanding rationality and discipline. On the other hand, the chaotic world of the arts and its vibrant, sensitive, and exuberant personalities. Certainly, this is a sketch of the more extreme images of science and art. The more contact one has with either of the two, the more nuanced this image becomes. There are scientists who don’t wear lab coats – the majority of us, actually – and there are artists who are not tormented by the capricious appearance and disappearance of the muse, but methodically follow work routines and rigorous methods. Even though at individual levels it is easy to admit that artists and scientists may share methods, ideas, and ideals, the step of generalizing this to the public image of art and science has not yet been undertaken.

The discussion that science and art are alien to each other is not new. Some place its origin in Charles P. Snow’s 1959 lecture “The Two Cultures”, though it is probably as old as the two formal fields of activity. In his lecture, Snow suggests that the intellectual life of Western society is split into two cultures – science and the humanities – whose people, for the most part, don’t speak each other’s languages and don’t share each other’s methods. This perspective is deeply engrained in the public perception of art and science, according to which the two seem to lead independent lives.

One of the main reasons for this schism may be that both art and science have an esoteric feeling about them. We are used to being exposed to their products, not their processes. We look at paintings, watch dance performances, or read poems, just as we find out about new treatments, gadgets, or the latest update on how global warming is progressing. What is in the space between the absence and the presence of these intellectual products? While the process of making art is portrayed as an artist’s intimate search for meaning, differing from artist to artist and impossible to synthetize in a formula, the process of conducting science is, on the contrary, illustrated as an impenetrable formula. Lacking the knowledge on the processes of art and science, the public is left with their bare products, which it uses to discriminate between the two. And indeed, the products of art and science are different in form, content and functionality. It is only natural to conclude that art and science are, too, wildly different from each other.

The current way in which art and science are communicated makes asking “How?” and receiving satisfactory answers arduous, which detracts most from further asking “Why?”. Being bound to asking “What?”, the public seems to have accepted a passive, consumer role in its relationship to art and science. Their fruits are either taken with no critical appraisal, or are ignored whatsoever. This might well be the most striking similarity between the two, albeit, not the only one. On a more fundamental level, both art and science are ways of exploring the world, rooted in our basic need for meaning and connection. This link between the two methods of exploration may not be obvious. However, when art and science meet, or, rather, when the conventional boundaries between them are blurred, it is difficult to ignore that both try to answer the same questions.

To our delight, there are more and more collaborative projects between artists and scientists who are open to blurring such boundaries and learning from each other. The Experiment series brought together a multidisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Groningen and the dance group Random Collision, who asked themselves in what way an audience is affected by what is happening on stage. Would different types of group solidarity in dance performance be reflected in audience’s sense of connectedness? And, crucially, is it possible for artists and scientists to open a dialogue, deconstruct expertise, and engage in a communal learning experience? Gloriously so. If The Experiment doesn’t prove that, the next project involving Random Collision shall.

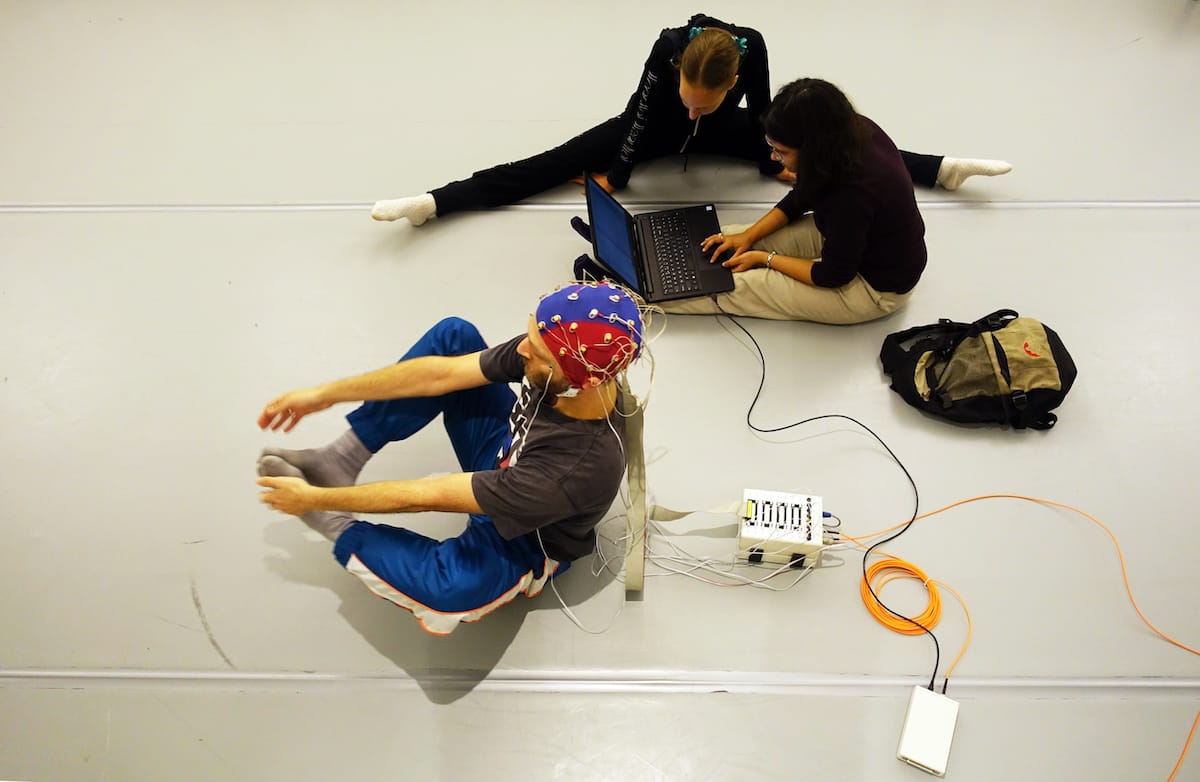

Notes on Synchrony is a living laboratory of brain and movement research. It is based on the (to me, poetical) finding that the brain waves of two (or more) people synchronize when they are engaged in a range of activities like dancing, singing, or playing instruments together, but also cooperating on certain tasks or agreeing within a debate. A group of neuroscientists from the UG and a group contemporary dancers set out to co-investigate the literal and metaphorical facets of this mental connection. In this exploration, science becomes oddly metaphorical, while art becomes loaded with scientific meaning. Imagine: dancers (wearing EEG caps) meet and part in a rhythmic drama of densely packed and deeply lived emotion, a poet writes and reads, a scientist observes and reports, a musician composes, a research assistant analyses incoming EEG (electroencephalogram) data, two visions (Kirsten Krans, who created the space for this dialogue to occur, and Marieke van Vugt, who studies inter-brain coherence in her lab) skillfully move the cables from the EEG caps between the dancers, showing a comparable degree of synchrony, connection, and commitment, while, finally, the public, having been offered cards and pens, takes notes on synchrony.

The relevance of these projects extends beyond their artistic and scientific value. By creating a space where art and science can organically and synergistically meet, they strip away some of the prejudices build around the two methods of exploration, revealing that the “What?”, “How?”, and “Why?” of art and science can (and, sometimes, should) be the same. What’s more, the process of exploration and learning in which artists and scientists publicly engage has the potential of involving the audience in a more meaningful way than otherwise possible. The audience may ask “Why?” and “How?” and be part of the conversation. This democratization of expertise may be just what we need to break the post-truth curse.