Mind, Body, Long COVID, and Statistics

Dutch media recently commented on a new publication by doctors and medical researchers from Amsterdam: “Long COVID has a physical cause.” For the study in Nature Communications, Brent Appelman and colleagues compared 25 patients with the diagnosis “long COVID” (average age: 41 years) with a control group of 21 healthy people.

In both groups, almost 100 percent of the participants have been vaccinated against COVID. To quantify the patients’ impairment, the researchers assessed their capacity to work: that severely decreased from 36 hours on average before the disease to only five when participating in the study.

As reviewed by Sandra Lopez-Leon and colleagues in 2021, more than 50 symptoms have been reported as long-term effects of a COVID-19 infection. The most common are fatigue (56 percent), headache (44 percent), attention problems (27 percent), hair loss (25 percent), dyspnea (shortness of breath; 24 percent), and anosmia (loss of smell; 21 percent). More psychological problems have been reported, too, such as memory loss (16 percent), anxiety (13 percent), depression (12 percent), and a sleeping disorder (11 percent).

Cycling for science

For the new study, Appelman and colleagues focused on fatigue, or more specifically, limited exercise tolerance and post-exertional-malaise. This does not only mean that patients have less capacity for physical exercise, but that they also remain more tired for longer – or that their state even gets even worse after the activity. This is also relevant for treatment, as many long COVID patients are offered physical exercise to (allegedly) improve their well-being.

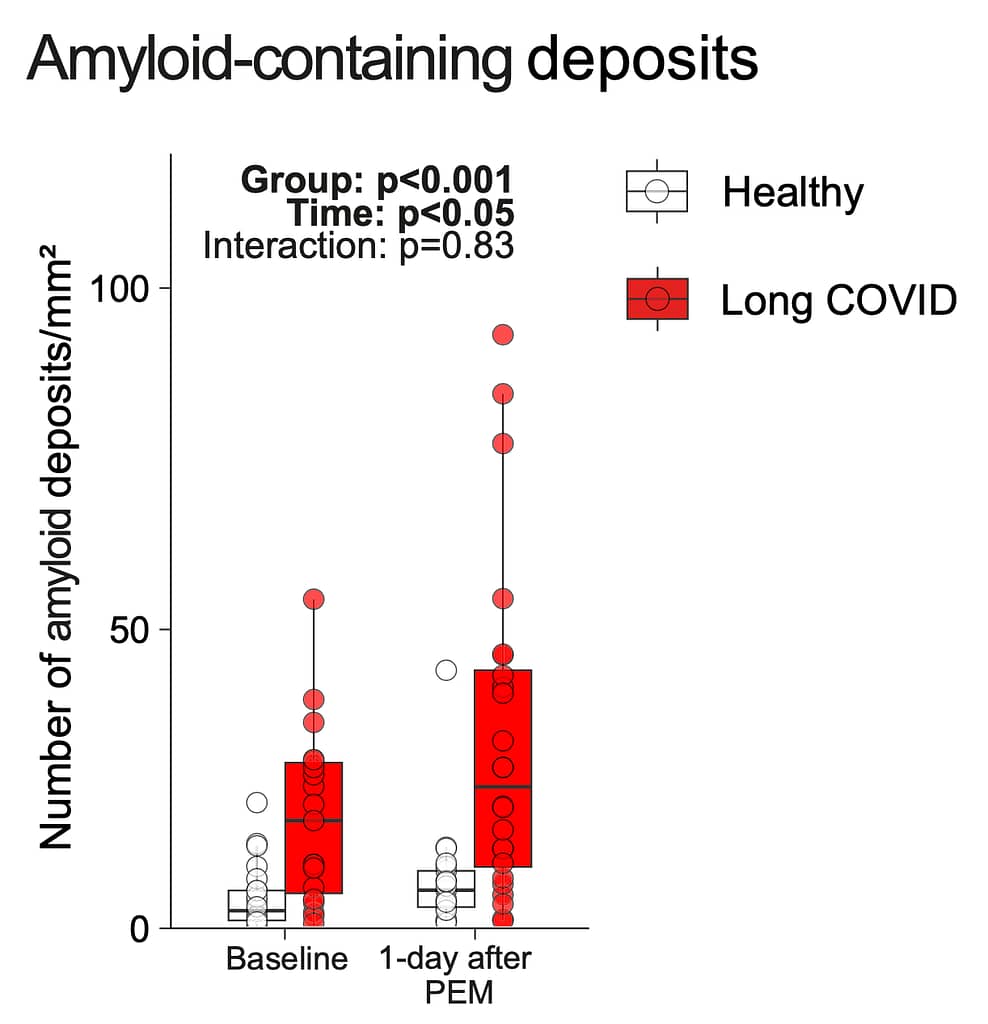

To assess this under controlled conditions, all participants performed a cycling task. The researchers then recorded several health-related measures. One of their central findings is that the patient group had significantly more amyloid deposits, a kind of protein, in their muscle tissue already before, but even more so one day after the exercise (see figure).

Figure: Participants with a diagnosis of long COVID (red) had significantly more amyloid deposits in their muscle tissue, particularly a day after the exercise. Source Appelman et al., 2024. License: CC BY 4.0 DEED

This is obviously a clinically important finding and suggests follow-up research: Can the deposits be prevented or broken down medically? And, if so, will that reduce the patients’ fatigue?

“Just between the ears”

More research has thus to be done. But we can still discuss some important questions, also related to what we teach our psychology students in statistics classes: First of all, as the researchers report (but the journalist gets wrong), the finding is only a statistical correlation and not yet a proven causal link; the follow-up research mentioned above could clarify this point.

Secondly, the accumulation of deposits was increased in (roughly) half of the patients. As we can see in the figure, there is much overlap between the patients (red) and the control group (white). This strongly suggests that the proteins, if they are causally relevant at all, aren’t the cause of fatigue in all patients. The media report thus looks premature, if not exaggerated.

A third and particularly psychologically relevant point is, in my view, that this biomarker (the amyloid deposits and some other but similar findings reported in the study) would prove that the patients’ problems are somehow “more real”, or, to use a common Dutch idiom: “not just between the ears”.

Well, what is it that we have between our ears? The heads, our brains, are thus the arguably most central and important part of our nervous system. And this, in turn, is essential for our psychological life and well-being.

Psychology is real

Indeed, probably ever since we talk about psychological problems or symptoms, people who suffer from them experienced pressure and/or difficulty that their suffering, that their impairment is real; or in other words: that they’re not just lazy or simulating.

I’ve just been reading related literature from the early 20th century. At that time, several countries (e.g., Germany or Great Britain) had introduced welfare institutions like various kinds of insurance for laborers. Sometimes, for example, personnel working on trains – which traveled slower back then, around 50 to 80 kilometers per hour only, but derailed or collided more frequently – would have a demonstrable physical injury after an accident; but sometimes the symptoms would be primarily psychologically, similar, arguably, to what we nowadays would call post-traumatic stress.

However, doctors who took psychological symptoms less seriously would ridicule the patients’ condition as “retirement neurosis”. That is, they would consider them as malingerers who fake the symptoms to receive public benefits.

When I now read in the year 2024 in the news that the patients’ representative is happy that the new study once and for all proved that long COVID is real, I must sigh. Because this unfortunately still communicates the idea that psychological symptoms are “less real”.

Imagine two cases

Why not turn that kind of reasoning around: Firstly, imagine that you had an organic condition, but no impairment or suffering; or, secondly, imagine that you had no organic condition, but a severely depressive mood. Which of the two cases seems worse? And how could someone call severe depression “less real” or “just between the ears”?

Of course, some consider depression (and other disorders) simply a “disorder of the brain”. We could understand this in the sense that all of our psychology is somehow related to the activity of our nervous systems. But it is, generally, still not possible to just look at a brain scan and then diagnose the patient’s mental health problem (see also Schleim, 2022).

Thus, for the time being, there is no “objective” biological proof of psychological suffering, although psychiatrists have been looking for it for more than 170 years. Still spreading the “psychological problems are less real” narrative, whether intentionally or not, may thus cause trouble for those suffering from them.

And just as some psychological problems justify a medical check-up – for example, thyroid dysfunction may cause a depressive mood –, it may sometimes be warranted to screen for psychological problems if a patient’s problem cannot be explained organically. But that’s, probably, something those who consider psychology as “just between one’s ears” don’t want to hear.

References:

Appelman et al. (2024). Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nature Communications, 15, 17.

Lopez-Leon et al. (2021). More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 11, 16144.

Schleim (2022). Why mental disorders are brain disorders. And why they are not: ADHD and the challenges of heterogeneity and reification. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 943049.

Title image: Gerd Altmann on Pixabay