I am a Monist (clearing up a misconception)

What do you think? Is the functioning brain identical with the mind?

If your answer is no, your stance is called Dualism: the belief that mind and body are made of essentially different substances. It is the stance adopted by Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, Charles Sherrington, and many others. This is countered by Monism, which states that the mind and the brain are one and the same thing. Its proponents include Ernst Mach, William James, and Bertrand Russell.

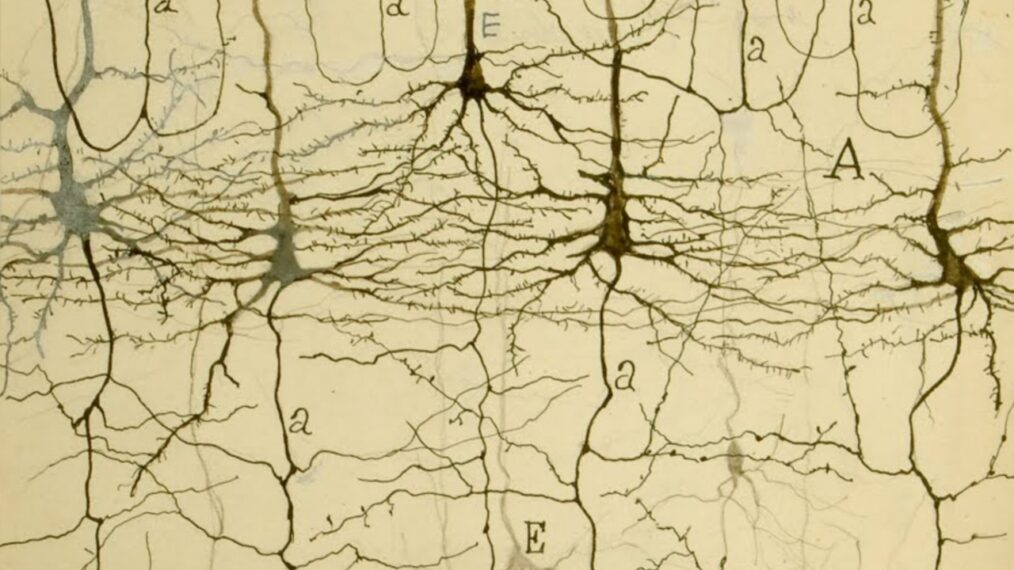

Neuroscientists typically support the monist idea of direct correspondence. They believe that the mind itself just is a biological process. Similar to how traffic conditions on roads emerge from the interactions of bicycles, cars, trucks, and pedestrians, so too does the mind emerge from the interactions of brain cells; of neurons in all their different shapes and functions, of the glia which serve and protect them, and of the neurochemical ebb and flow in which they all bathe.

For anyone unfamiliar with neuroscience, this materialist view may seem reductionistic, unintuitive, and hard to believe. One can imagine the reaction: “How do a bunch of chemicals love my family?”

On this view, any thought and every feeling is not only biological, but also electrical and chemical. That means that all we are or want to be—our identity, our memories, dreams, desires, hopes, plans, ideas, faiths, opinions, thoughts, and feelings—not only have, but indeed are their corresponding electrical signals and chemical reactions within the arrangement of our biological tissue. They are all simply the activity of a biological machine: the brain.

Just recently I saw a short blogpost by Arthur Khachatryan, in which he points out that assuming monism’s materialism will lead psychology—as the study of the mind—to abolish itself. As he put it:

And were it not for this dualism of the brain/mind phenomenon, psychology would be a superfluous undertaking. What are we actually doing by reducing the mind to mere biochemistry? The person carrying this out is essentially saying, ‘I (the non-existent concept of the self or the ego) am nothing but a mere composition of atoms, elements, chemicals.’

But, if this is true then we should have no cognitive capabilities or reason for postulating that “reality.” Mere chemicals [and their interactions] do not have cognition or trustworthy reasoning capabilities to make such claims. Reductionism is, therefore, self-defeating at its core.

Khachatryan, though, repeats a common misconception: that monism’s reduction of mental processes to biological processes means denying the presence of the mind. Or its relevance to science.

Even the famous Dutch neuroscientist Victor Lamme based his “Weg met psychologie!” (Get rid of psychology) argument on this misconception. This argument also forms the core of theologians’ critiques of neuroscience, who frequently argue that no non-physical mind would mean no mind at all (Griffith, 2014).

What many don’t notice, though, is that this dismissal of monism rests on a dualist assumption. The interpretation that produces the dismissal is two-sided, rather than both reflecting the same source.

The argument can be summarised like this: there is no mind beyond biological processes, therefore the mind does not exist, because the mind is not a biological process (according to monism). But my mind must exist because I can feel it; I have evidence of it. So monism must be wrong. Cogito ergo sum, as Descartes wrote: I think therefore I am.

This is a perfectly valid line of reasoning. But only as long as “the mind” is defined as something beyond biology. That would be dualistic: the belief that the mind is made of a fundamentally different substance from the brain.

Here’s the problem: monism posits that the mind itself is a biological process. All of it. Assuming a direct correspondence of mind-activity and brain-activity, they are one and the same. Whenever one studies the brain, one also indirectly studies the mind. And when one studies the mind, one also indirectly studies the brain.

Why should these perspectives be at odds with each other? As a monist, I don’t think they are.

Lastly, I would like to briefly explain why I became a monist myself. Because I hope that you, dear reader, might become one too.

I became hooked by the outcomes of some of the least fortunate injuries one can have, those, who could rip out a part of my self. Such as, the part of me that is afraid of anything but suffocation (Feinstein et al., 2013). Or the part of me that prevents me from acting like a jerk (Wood & Worthington, 2017). At the same time, experience shapes my brain in the very literal sense of the word. And if the experience is powerful, such as a childhood locked away in the grey halls of a Romanian orphanage for children the society gave up on, then the emotional scar would weaken my brain, which would grow smaller and even produce weaker electricity (Chugani et al., 2001). In short: if the experience is intense and enduring, an emotional scar may be so large that we can use a brain scanner to take a picture of it.

With every new memory your brain changes, in any second, new connections between cells form and disappear. Any change in me, as small as it might be, is a change in my brain. While writing this text, my brain changed once again. As I connected the ideas that you are reading, I was slow and spent hours structuring my argument. Now I can lay it out in minutes. Somewhere in my brain, I created this network of mental ideas. And I just planted it in your brain too.

References

Chugani, H. T., Behen, M. E., Muzik, O., Juhász, C., Nagy, F., & Chugani, D. C. (2001). Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: a study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. NeuroImage, 14(6), 1290-1301.

Feinstein, J. S., Buzza, C., Hurlemann, R., Follmer, R. L., Dahdaleh, N. S., Coryell, W. H., Welsh, M. J., Tranel, D., & Wemmie, J. A. (2013). Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage. Nature Neuroscience, 16(3), 270-272.

Griffith, T. (2014). Does the Soul Exist? An Intersection Between Neuropsychology, Philosophy of Mind, and Evangelical Christianity.

Wood, R. L., & Worthington, A. (2017). Neurobehavioral abnormalities associated with executive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 11, 195.

Feature graphic by Santiago Ramón y Cajal,

Royal Academy of Medicine of Spain, Madrid