Facebook’s Manipulations

On 17 June, researchers affiliated with Cornell University, the University of California in San Francisco, and Facebook Inc. published a study of emotional contagion. By manipulating the News Feed of Facebook users (N = 689,003), they reduced either the number of positive or negative emotion words users were exposed to. They then measured the number of positive or negative words these same people subsequently used in their own posts, and indeed found evidence for what they suggested is emotional contagion: users in the experimental group who were exposed to fewer positive words than the control group (whose News Feeds were left undisturbed) produced fewer positive and more negative words. The opposite was true for users exposed to fewer negative words. The results are statistically significant, but the effect is tiny.

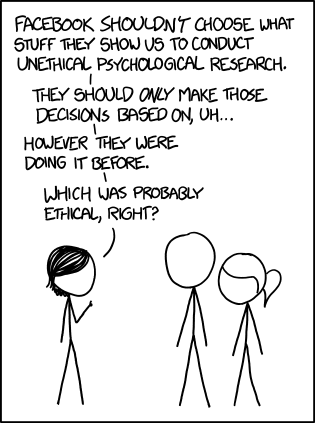

To most people, more remarkable than the study’s results were the ethics of the experiment. The Facebook users involved did not give informed consent, nor were they debriefed. As Katy Waldman formulated it in Slate:

Facebook “intentionally manipulated users’ emotions without their knowledge”.

Others have defended the study: it’s simply a part of Facebook’s ongoing effort to improve its service, and at least this time the results were published – open access even. And besides, no harm was done. Reading more or fewer emotion-related words in your News Feed is not going to upset your mental balance. People aren’t made of spun glass, as someone put it.

In my opinion, the question of harm is irrelevant. Even if there is no risk for the participants, informed consent is mandatory in behavioral research. It is, firstly, not up to the researchers to decide whether the experiment is potentially harmful: that is for the participants themselves to decide. Any other arrangement would be paternalistic. And secondly, it is crucial that people participate voluntarily. Granted, there is a provision in the small print of Facebook’s terms of agreement about the company’s right to use user data for research. Moreover, even if they didn’t read the terms of agreement before clicking “accept”, most Facebook users are aware they sold their soul to the company when they signed up. However, it rather stretches the meaning of the term to call this “informed consent” and publishing your findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences hardly constitutes “debriefing”.

The point of informed consent is not to avoid harm, it is to make sure that behavioral research is not just about people, but is done with and for people.

Informed consent forces researchers to consider the interests of their experimental subjects, and the people they study in general. And it works both ways, because informed consent likewise forces the participants to consider the interests of the researchers and think about the subject they study. The fact (if it is a fact) that most participants don’t care (they’re just in it for the credits) is not an argument for not taking informed consent and debriefing seriously, rather the reverse: it means they are not as interested in behavioral research as they should be, and we must try harder to argue for its value.

Relevant Publications and Links

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201320040. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320040111

Waldman, K. (2014, June 28). Facebook’s Unethical Experiment. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2014/06/facebook_unethical_experiment_it_made_news_feeds_happier_or_sadder_to_manipulate.html

NOTE: Images by mkhmarketing, licenced under CC BY 2.0 and xkcd licenced under CC BY-NC 2.5

I was rather surprised to see this, not so much because I thought Facebook was above this sort of thing, but because it appeared to be in breach of US federal rules, as described by the Department of Health and Human Services (link: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.101). The waters of federal regulations and who has to adhere to them when it comes to work with human subjects, are murky, though. PNAS has since published a correction (link: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2014/07/02/1412469111.short) on the article, shedding a bit of extra light on this matter. The so-called “Common Rule” of the HHS is the relevant section, but Facebook Inc., as a private company, does not have to conform to it. What about the terms and conditions for Facebook users? Did we all sell away our soul, as Maarten says? And what exactly did we sell it for? According to the terms and condition of Facebook Inc. (does anyone actually read those?), some user data may be used for research purposes, but this change in the policy was made AFTER the study data were already collected (link: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jul/01/facebook-data-policy-research-emotion-study).

The dust is still settling on this matter; actually, it seems it will take a while for it to settle properly, if at all. In the meantime, it will be interesting to read the commentary on all this and see just how all the sides set up their camps. PNAS have already come out to express their concern about the ethics of the study (link: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jul/04/journal-published-facebook-mood-study-expresses-concern-ethics) and at least a few countries have opened up inquiries. Facebook has apologised because the study was “poorly communicated” (link: http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/07/02/facebooks-sandberg-apologizes-for-news-feed-experiment/) and plenty of academics have voiced their opinions on the ethics (just one example: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/doing-good-science/2014/06/30/some-thoughts-about-human-subjects-research-in-the-wake-of-facebooks-massive-experiment/) and methods (link: http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2014/06/23/emotional-contagion-on-facebook-more-like-bad-research-methods/) of the study. We’ll see what all of this brings for us, but the discussion is welcome.

What are Mindiwise readers’ opinions about this?

-t

I am actually curious to hear how this type of study is different from field experiments such as one in which random (?) people are given flyers on the train station by either a light-skinned person or a dark-skinned person, and the researchers assess the percentage of flyers that is thrown on the street rather than in a waste bin. “Participants” in these experiments are not asked for their consent either. Is this okay as long as the people remain anonymous?

Aside from the ethical issues w.r.t. informed consent, the authors violate – in my opinion – another ethical issue by massively exaggerating the importance of their findings.

When you read the “key findings” section (which PNAS calls “significance”) or the abstract, there is not one single word on effect size. They present their ‘significant’ findings in the abstract as if they really matter: “when positive expressions were reduced, people produced fewer positive posts and more negative posts; when negative expressions were reduced, the opposite pattern occurred.”

That’s utter nonsense: the only correct conclusion from the large-scale study is that no relevant pattern whatsoever has been found.

You need to read the full paper in order to find out details on the effect sizes. They are reported (because APA demands it) but they are not reflected on. They should have and the lack of it would be a valid reason to fail a Bachelor’s thesis – and a publication in PNAS is on a whole other level.

An example of a reflection on effect sizes: “[when the number of positive posts is reduced, the percentage of words that were negative increased by B = 0.04% (d = 0.001).] This means that, on average, in the period of time where a regular user would use 2500 negative words on Facebook (which, I think, would be at least a number of months), a user which is presented with fewer positive posts would use about 2501 negative words. Thus, we can conclude that we found no relevant influence of altering the information on a Facebook feed on Facebook users’ emotional state.” In their abstract, the authors claim nearly the opposite. Unethical.

Re Marije’s comment: I realize that informed consent can be difficult to arrange in a field experiment. Fully informed consent, with a signature and all, may be impossible to realize, but I don’t think the formalities are the main point. One can still attempt to inform the public as much as possible, via an article in a local newspaper for example. In a case like the Facebook study, it would have been even easier: simply send a message to users globally describing the kind of study they want to do, and offer an opt in or opt out possibility.

Marije,

Aside from the fact that, as Casper says, the results are grossly exaggerated, one of the differences (not the only) in the two examples is that of setting. A person who walks around the train station has essentially already consented to having his/her behaviour observed (it’s a public place). Facebook News Feeds and pages are still considered ‘private’ by many (don’t ask me to define this, in Facebook terms).

-t

I completely agree with Casper. The effect size is extremely extremely small, and the actual change is really really small. Completely meaningless. I don’t understand how it was published with the way it was written, in addition to the other ethical issues.

The smoke is still there: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/09/facebooks-mood-manipulation-experiment-might-be-illegal/380717/

It’s a bit unfortunate that the fact that Facebook published its results means that is falls under the Common Rule that prescribes informed consent. Next time, they will just not publish the results and avoid the hassle. That would be a pity, because I think publishing is the one thing they did right. I think the legal aspect is secondary: the main thing is that you involve the participants in the research that you’re doing on, with, and about them, and the point is to close the gap between science and public.