Do you see what I mean?

Imagine being on top of a mountain. Imagine gazing far off into the distance; to the infinite horizon. Endless. You see other mountains rising out of the landscape, reaching high into the sky, and blanketed in white snow. Two birds float effortlessly, as if the sky itself belongs only to them. Picture the whole mountain range. It is spectacular, and breath-taking.

Many of us enjoy these imaginative journeys: reliving events from our past, conjuring visions of the future, or getting lost in a favourite book. Yet the ability to imagine shouldn’t be taken for granted. Whereas this description of the mountains might elicit a vivid and colourful scenery in your mind’s eye, some people are unable to visualize images like these in their heads. They are blind inside.

The inability to voluntarily paint mental pictures in one’s head is called aphantasia. The word stems from two Greek words: a meaning “without”, and phantasia meaning “imagination”. It is estimated that around 2% of the population is affected by aphantasia (1). At the same time, however, the phenomenon is largely unstudied. And public awareness is still rather low. Many more people might be affected than we currently know.

One reason aphantasia may have gone unstudied for so long is that it isn’t necessarily a problem. It is not a disability per se, but a different way of experiencing life.

Many people are not even aware that subjective experiences can be so different from their own. Indeed, this is often one of the first lessons a university freshman learns when starting off the year in a psychology class.

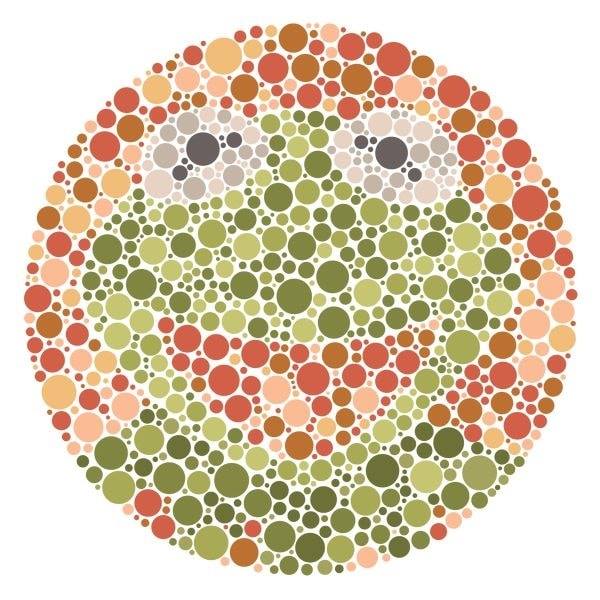

Usually illustrated with a colour blindness test, such as the Ishihara Colour Vision Test, students discover that the same image can be seen in different ways. A person with “normal” colour vision will see a single- or two-digit number in an array of differently coloured dots, or a recognizable image, whereas someone who is “colour blind” will either see a different number or won’t be able to see a number at all. But colour perception (and perception in general) varies greatly, and sensory impressions are interpreted individually. And this is often forgotten: most people assume that what happens in their own head is pretty much what happens in everybody else’s head.

Aphantasia is similar: there is no “colour” in the imagination. The imagination, however, is a much richer and more complex concept. So the inability to visualize does not necessarily imply an inability to imagine (2).

Even though mental visualization may not be required for imagination, for most of us, it represents a key ingredient for imagination. But never underestimate the power of visualization.

Visualization can both be advantageous and disruptive. On the one hand, research shows that the effective use of mental imagery can accelerate learning and improve performance in multiple contexts (3). Specifically, mental practice seems to increase reading comprehension and learning word-meanings in schoolchildren (4). And it can promote recovery in stroke patients to regain function of their paralyzed limbs (5). On the other hand, very strong mental imagery – also called hyperphantasia – plays a core role in several clinical disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, and many anxiety disorders (6). For example: in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sufferers experience vivid and intrusive flashbacks of their traumatic experience in the form of mental images. Yet these are mostly involuntary sensory experiences.

When people talk about the mind’s eye, they normally refer to a conscious visual experience (6). Surprisingly, aphantasics are still able to have involuntary visualizations like dreams (2). So why is it that they can dream in pictures but cannot voluntarily call images to mind when they are awake?

Adam Zeman, professor of cognitive and behavioural neurology at the University of Exeter Medical School, describes dreaming as a ‘bottom-up’ process that originates in the brainstem, whereas consciously visualizing and daydreaming is a ‘top-down’ process that is driven by the cortex. This then explains the differences: “what the brain is doing in wakefulness and dreaming is different” (7).

However, the causes underlying aphantasia are still largely unknown. Most people have had aphantasia since birth, but others have acquired it following a brain injury, or sometimes after periods of psychosis or depression (7). It is known, however, that visual memory appears to be unaffected: aphantasics are able to describe in detail the characteristics of certain people and objects, even though they cannot see them in their mind’s eye (8).

We are thus left with a variation of what Atticus Finch tells his daughter in To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb into his skin and walk around in it” (9). The simple wisdom of Finch’s words is a gentle reminder that individuals perceive the world differently and that we can never fully know what is going on inside someone else’s mind.

Imagination is powerful, but mental lives without mental imagery can still be fulfilling and rich. They are different from ours and remind us of the great, but easily unnoticed range of variation in human experiences. Even if you can’t imagine what it’s like, always remember that people perceive the world differently than you do.

References

- Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery—Congenital aphantasia. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 73, 378–380. https://doi-org.proxy-ub.rug.nl/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.019

- http://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/exeterblog/blog/2015/08/26/aphantasia/

- Schuster, C., Hilfiker, R., Amft, O. et al.Best practice for motor imagery: a systematic literature review on motor imagery training elements in five different disciplines. BMC Med 9, 75 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-75

- Jenkins, M. H. (2010). The effects of using mental imagery as a comprehension strategy for middle school students reading science expository texts.http://gateway.proquest.com.proxy-ub.rug.nl/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&res_dat=xri:pqdiss&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:3372865

- de Vries S, Mulder T. Motor imagery and stroke rehabilitation: a critical discussion. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2007 Jan;39(1):5-13. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-0020. https://www.jsmf.org/meetings/2008/may/de%20Vries%20&%20Mulder%202007.pdf

- Pearson, J. (2019). The human imagination: The cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 20(10), 624–634. https://doi-org.proxy-ub.rug.nl/10.1038/s41583-019-0202-9

- https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/aphantasia-life-with-no-minds-eye/

- Jacobs, C., Schwarzkopf, D. S., & Silvanto, J. (2018). Visual working memory performance in aphantasia. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 105, 61–73. https://doi-org.proxy-ub.rug.nl/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.10.014

- Lee, Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006.

Dank voor dit interessante artikel, het is voor het eerst dat ik over deze conditie hoor, en het is voor mij kristalhelder dat ik die ‘conditie’ heb. Mijn leven lang probeer ik mensen al uit te leggen dat ik echt helemaal niets, zelfs geen leeg blad, voor mijn ‘geestesoog’ zie. Voor mij is dit in de verste verte geen probleem (behalve dat telkens maar weer moeten uitleggen en tegen een ongelovig gezicht aankijken), omdat ik a) wel dingen zeer goed hoor, voor mijn innerlijk oor kan ik het verschil horen in uitvoering van de schilderijententoonstelling op piano, door orkest of de versie van Isao Tomita. En b) ervaar ik de wereld als een serie tastbare relaties in een abstracte ruimte. Ik ‘zie’ hier niets, maar de ‘tastzin’ helpt me prima om me zeer ingewikkelde problemen (ik heb meegewerkt aan de ontwikkeling van fMRI en Optical Shape Sensing) voor te stellen, ontdaan van alle niet essentiele franje. Ik kan ook van alles fantaseren en me in’beelden’ trouwens (moet ik het in’tasten’ noemen?). Als ik andere mensen hoor vertellen denk ik soms wel eens dat ik iets mis, maar daarentegen hebben die anderen meestal geen idee waar ik het over heb als ik over die tastzin praat, dus in die zin ben ik dan weer rijker.