Collective discontent, polarization and protest

Tom Postmes wrote this blog post based on his keynote presentation at The Social Animal event organized by ASPO and KLI in Tivoli Vredenburg in Utrecht.

We live in turbulent times. Concerns about polarization and popular discontent are commonplace. Democracies are giving way to authoritarian rule. Internal divisions are causing intense governmental challenges (Brexit, Trump). And on the street of our Western societies, we see the return of protesting crowds and occasional mass violence.

So for many reasons, this seems a better time than ever to ask the question: what do we really know about such mass movements and societal sea-changes? We have been trying to answer this question for the past 7 years now. Some of the research we have done has been commissioned by various Dutch ministries. For them, the key concern is to keep the Netherlands safe and stable. For us, it’s a great opportunity to tackle big issues: what do we really know about these societal phenomena we are witnessing today?

“The general knowledge among the public and (more worryingly) among many experts and policy makers consists of stereotyped beliefs about crowds and group dynamics that are mostly untrue and often entirely unhelpful.”

We covered lots of topics in our research over the years, but in this blog post I highlight four central findings. To begin: what is the state of general knowledge about crowds and their mass psychology and group dynamics? The short answer: pretty poor. The general knowledge among the public and (more worryingly) among many experts and policy makers consists of stereotyped beliefs about crowds and group dynamics that are mostly untrue and often entirely unhelpful. It is not so surprising that these common beliefs are widespread: studying crowd phenomena is difficult and time-consuming. But after a riot or a major disaster, people want instant answers: “how could this happen?” is top of mind. In practice it can take months (or even years) to answer that question. By this stage, the general public has lost interest: only a very small audience of experts ever finds out that the initial explanations were wrong. The next time an incident occurs, the same old stereotypical explanations are wheeled out. As a consequence, lay theories of the crowd have evolved only little since the late 19th century.

Figure 1. Twelve common beliefs about crowds. These are often presented as “simple truths” that can explain crowd events such as riots or disasters. They are often wrong and always unhelpful (Postmes, van Bezouw, Tauber, & van de Sande, 2013, https://www.rug.nl/staff/t.postmes/socialeonrust_postmes.pdf)

- It is easy to explain crowd behavior

- Every crowd is inherently dangerous

- Crowd members are irrational

- The crowd is swept along by emotions (panic, aggression)

- People in the crowd all act the same

- Violent crowds consist of bad people

- Crowds are guided by troublemakers

- Crowds act out of deprivation

- Riots are caused by police brutality

- Riots are caused by a spiral of violence between two or more groups

- Riots can easily be prevented

- Riots are caused by alcohol and drugs

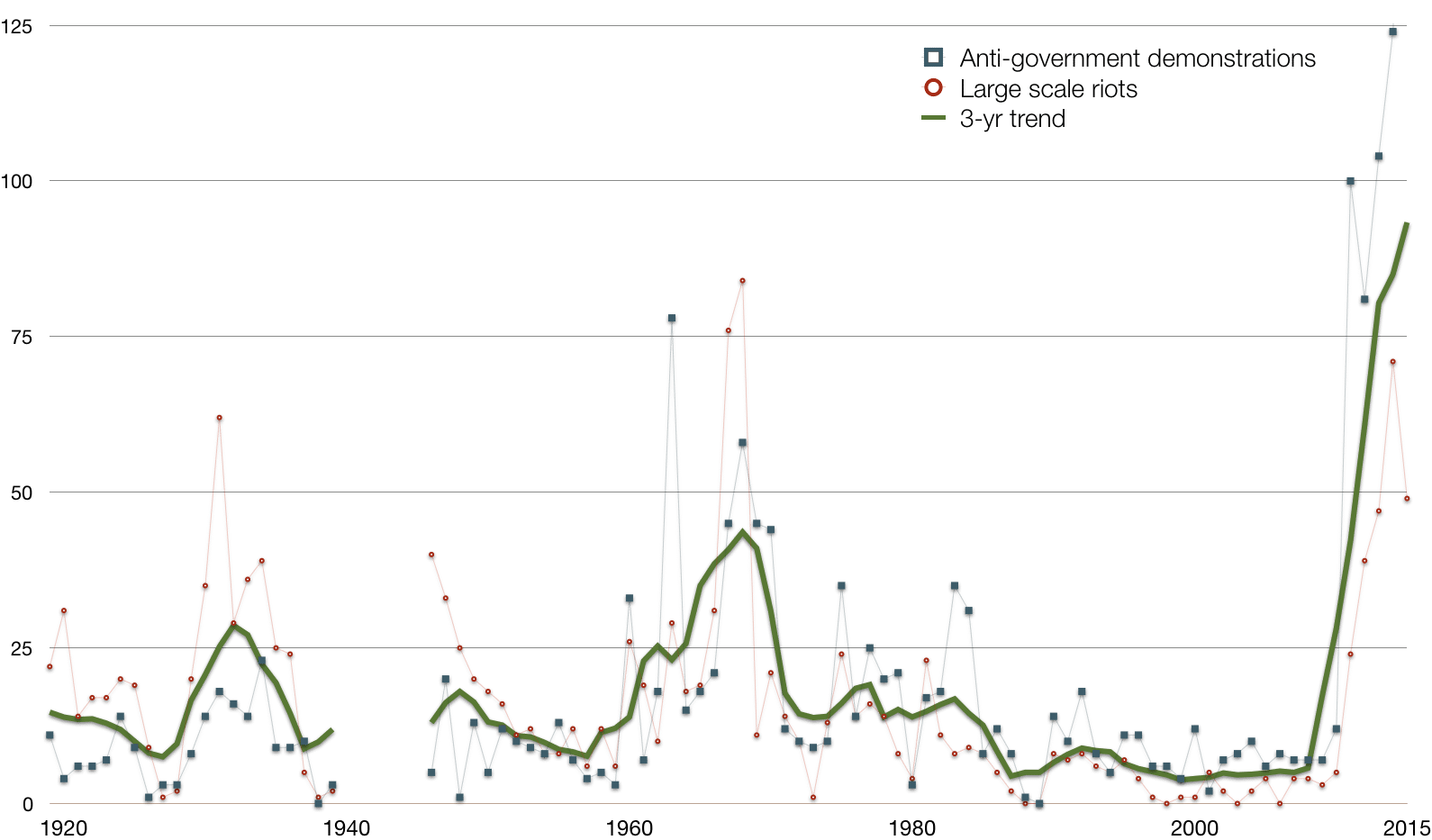

A second central finding is that today we are in the grip of a worldwide protest wave. In the 1990s and 2000s, historical evidence suggests that large-scale protest was at an unprecedented low point in OECD countries. Protesting became seen as outdated and “a thing of the past”. But since 2010, we see a marked upswing in major nationwide protests as well as in large scale riots.

“Protesting became seen as outdated and “a thing of the past”. But since 2010, we see a marked upswing in major nationwide protests as well as in large scale riots.”

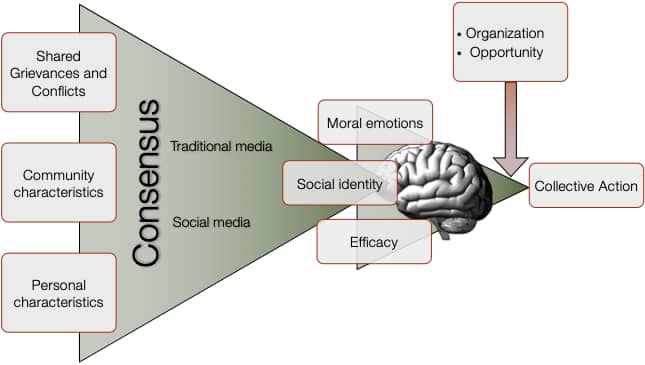

Third, why do people come onto the streets in large numbers? The traditional thinking is that when people have a grievance or when they are deprived, they are motivated to protest. Others suggest that people need to see an opportunity or see gains. But these are all just ideas in the minds of individuals: this is not how protest works. After all, we are seeking to explain collective behavior. When people protest, this always has a social dimension: at minimum, people have to approach another person to register their grievances, for example by complaining. If this has to be done by multiple people (in a village, say) this means people need to come together, to agree and then to organise themselves. This is never easy. As a result, collective action is always the result of a lot of hard work. And in the background of taking action, there is an ongoing process of seeking to establish consensus with others: what is going on here? Why is this happening? What can be done? In all of this, it helps a lot if there is another group (an “outgroup” such as the government or a corporation) that makes collective action possible by behaving badly.

“The traditional thinking is that when people have a grievance or when they are deprived, they are motivated to protest. But these are all just ideas in the minds of individuals: this is not how protest works. When people protest, this always has a social dimension”

Figure 3. A graphical display of some of the factors involved in large-scale collective action. (Postmes, van Bezouw, Tauber, & van de Sande, 2013)

For example, we studied the collective action in the Dutch province of Groningen (against Shell/Exxon and against national government) these past years (Greijdanus & Postmes, 2019). We see that people begin taking individual actions (see also Stroebe, Roos and Postmes, 2018), but over time collective action increases sharply. Along their personal trajectory towards more radical forms of activism, we see that among Groningers, people initially experience a sense of individual inefficacy: their personal actions to claim damage do not have the desired result. They also come to agree that this is a collective problem and an injustice, not just a problem of individual house owners. They see the state and corporations as responsible, and they begin to organize themselves and organize events to make themselves heard. This development is strengthened when states and corporations downplay what is happening and display a lack of empathy (for example by saying that “no one has died yet”). Collective action is also more likely if there is a sustained failure to address root causes. And violence becomes possible if the other side uses force in an illegitimate way. All these things, in Groningen, are contributing to increasing protest and even radicalization.

“All these things, in Groningen, are contributing to increasing protest and even radicalization.”

And finally: how about this wave of discontent that seems to engulf Western society? Will we see yellow vests everywhere, will this end in massive societal disruption, a populist revolt or civil war? First we should ask: what is collective discontent? According to our research, the essence of discontent is a shared conviction that society as a whole is doing badly (Van der Bles, Postmes, & Meijer, 2015; Van der Bles, Postmes, Lekander-Kanis, & Otjes, 2018). Particular subgroups are convinced that society as a whole is, as it were, “rotten to the core”. This is not due to one issue or one particular wrong: it is much more vague and global than that. According to our recent research, one of the core concerns behind collective discontent is the shared belief that society is failing to take good care of people who are in need (Postmes, Gordijn, Kuppens, Gootjes, & Albada, 2018).

“How about this wave of discontent that seems to engulf Western society? Will we see yellow vests everywhere, will this end in massive societal disruption, a populist revolt or civil war?”

But while it is troubling that about 20% of the Dutch appear to hold these beliefs about society, such beliefs do not mobilize people in and of itself. So under what conditions does collective discontent lead to large scale unrest? In the Netherlands we have not seen this happen yet, so we can only speculate. We know from research that particular incidents or events can confirm people’s beliefs that society is failing. After such events they might experience anger, indignation or outrage: these are exactly the kinds of emotions that play a role in mobilizing people for action. So we speculate that protests against for example immigration policy might be happening for multiple reasons. People who dislike migrants may be motivated to protest because they expect this might keep migrants out. But people who have a deep sense of collective discontent about society may join them in protest, not necessarily because they have anything against migrants, but because they see this as an opportunity to voice their concern about government policy. In such a way, particular incidents or events might lead to protests that can become very large indeed.

In sum, many different factors have to come together for large groups of people to take to the street in protest. In this short post I chose to explain only four of our insights. There is a lot more to say of course: see below for pointers to additional reading.

Readings

We have integrated insights about discontent, protest and civil unrest in a series of projects. The first was an overview of state of knowledge about large scale civil protest, commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of the Interior (in Dutch, see here). We later linked this to societal discontent and to conflict escalation, in a study commissioned by the Ministry of Safety and Justice (in Dutch, with English summary: click here). A recently completed study, commissioned by the same ministry, examined the role of social media in protests surrounding the gas extraction in Groningen (click here). Finally, we are monitoring discontents and fears about migration and their consequences. An initial report focusing on public support for migration can be found here, and the full report will come out towards the end of 2019.

Other references

van der Bles, A. M., Postmes, T., & Meijer, R. R. (2015). Understanding collective discontents: A psychological approach to measuring zeitgeist. PloS one, 10(6), e0130100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130100

van der Bles, A. M., Postmes, T., LeKander‐Kanis, B., & Otjes, S. (2018). The Consequences of Collective Discontent: A New Measure of Zeitgeist Predicts Voting for Extreme Parties. Political Psychology, 39(2), 381-398. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12424

Stroebe, K., Postmes, T., & Roos, C. A. (2018). Where did inaction go? Towards a broader and more refined perspective on collective actions. British journal of social psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12295

NOTE. featured image by Hedy Greijdanus.