Activism: A very personal project of change

Activism can change the world that we live in. For example, in 2010 the Arab Spring reshaped many of the Arab nations, and set off wider actions around the world. This included an explosion of anti-government protests and civil unrest in the West, which even exceeded levels recorded in the tumultuous 1960’s. More recently, grassroots movements of ordinary citizens were largely credited with the election of the new US President, Donald Trump, even though he (at least initially) had little support from the Republican Party Elite he represents.

“Engaging in activism is typically not in the interests of the individual: Not only does it come with personal costs (e.g., time, energy, stress), but accepting these costs is almost always irrational”

But why do normal citizens take to the streets in the first place? This has proven difficult to explain, because it is often thought that individuals act in their self-interest, whereas engaging in activism is typically not in the interests of the individual. Not only does it come with personal costs (e.g., time, energy, stress), but accepting these costs is almost always irrational. This is because if the movement succeeds, it benefits not only those who acted in it, but also bystanders who invested nothing. So, understanding people’s choice to take part in activism cannot be understood as a rational process of weighing the costs versus benefits of action. Instead, to understand why people take part in this seemingly irrational behavior, we need an approach that can move beyond economic explanations of action.

“The more committed an individual is to a political movement, the stronger their movement identity, and the more likely they are to engage in political action.”

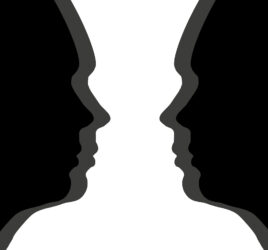

From a social psychology perspective, an important factor that influences if an individual will join a political movement is their identity. The more committed an individual is to a political movement, the stronger their movement identity, and the more likely they are to engage in political action (e.g., van Zomeren, Postmes & Spears, 2008). But why individuals identify with the movement in the first place is less clear. This is particularly important because the shift from seeing the self as non-political to seeing the self as an activist can require big changes in one’s identity. My research suggests that at least three key identity changes take place in individuals as they become activists.

A first identity change that occurs when a person begins to see themselves as an activist, is that the political and personal become integrated (Turner-Zwinkels, van Zomeren & Postmes, 2015). Practically, this means that this means that “I demonstrated recently against injustice” becomes “I am someone who fights for justice”. Psychologically, this means that an individual is experiencing a better fit between who they are and who a movement member is, so that they may be increasingly likely to see themselves as a movement member, too. The result is that political goals become personal goals, and can be pursued actively, even if there are costs involved for the individual.

“Together, these moral building blocks within the activist identity help to make activists strong, protecting them from criticism and motivating them to take part in more effective action.”

A second identity change that occurs in political movement members is that movement members are more likely to see themselves as moral, honest, and sincere (Turner-Zwinkels, van Zomeren & Postmes, 2016). Practically, this is an important step because morals may help fulfil two functions for activists. Firstly, seeing the self as moral may help to inspire passion and motivate individuals to fight for their cause. Secondly, seeing the self as moral may be important for maintaining action, because a moral self-image can help buffer the self from the threat of being criticized by others. Together, these moral building blocks within the activist identity help to make activists strong, protecting them from criticism and motivating them to take part in more effective action.

“My research suggested that devoted activists applied their political ideas more widely throughout their lives. So, activists may not only act like activists while at a demonstration, but also when they are at home or work.”

A third and final identity change is that the activist identity may come to define a person’s life in general (Turner-Zwinkels, Postmes & van Zomeren, 2015), similarly as religion does. Just as a ‘good’ Christian should follow biblical teachings not only when in Church but across life in general, so too should ‘good’ activists broadly apply their activist ideologies to their life. Indeed, our research suggested that devoted activists applied their political ideas more widely throughout their lives. So, activists may not only act like activists while at a demonstration, but also when they are at home or work. It may be important for activists to define their life with activism like this, because activism is not just about participating in a demonstration once. It requires repeated action engagement, and long-term commitment to social movement goals. This devotion may help activists overcome personal costs of participation over long periods of time, and help movements to succeed in their goals.

Altogether, my work on the topic of activism suggests that identity changes may be at its center, by transforming a passive citizen into an activist.

Altogether, my work on the topic of activism suggests that identity changes are at its center, by transforming a passive citizen into an activist. This research therefore provides scientific support for the intuitive idea that activists go through a personal transformation, which is quite central in popular accounts of activism. My research highlights activism as a psychological process that truly transforms individuals and who they are: The political becomes personal, moral, and self-defining. Together, these identity changes help to create an inner obligation to action, which means that the personal costs of political action may not be not felt so strongly anymore.

References

Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., van Zomeren, M. & Postmes, T. (2015). Politicization during the 2012 US presidential elections: Bridging the personal and the political through an identity content approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(3), 433-445. doi: 10.1177/0146167215569494.

Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., Postmes, T., & van Zomeren, M. (2015). Achieving Harmony among Different Social Identities within the Self-Concept: The Consequences of Internalising a Group-Based Philosophy of Life. PloS one, 10(11), 1-31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137879

Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., van Zomeren, M. & Postmes, T. (2016). The moral dimension of politicized identity: Exploring identity content during the 2012 Presidential Elections in the USA. British Journal of Social Psychology. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12171

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological bulletin, 134, 504-535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

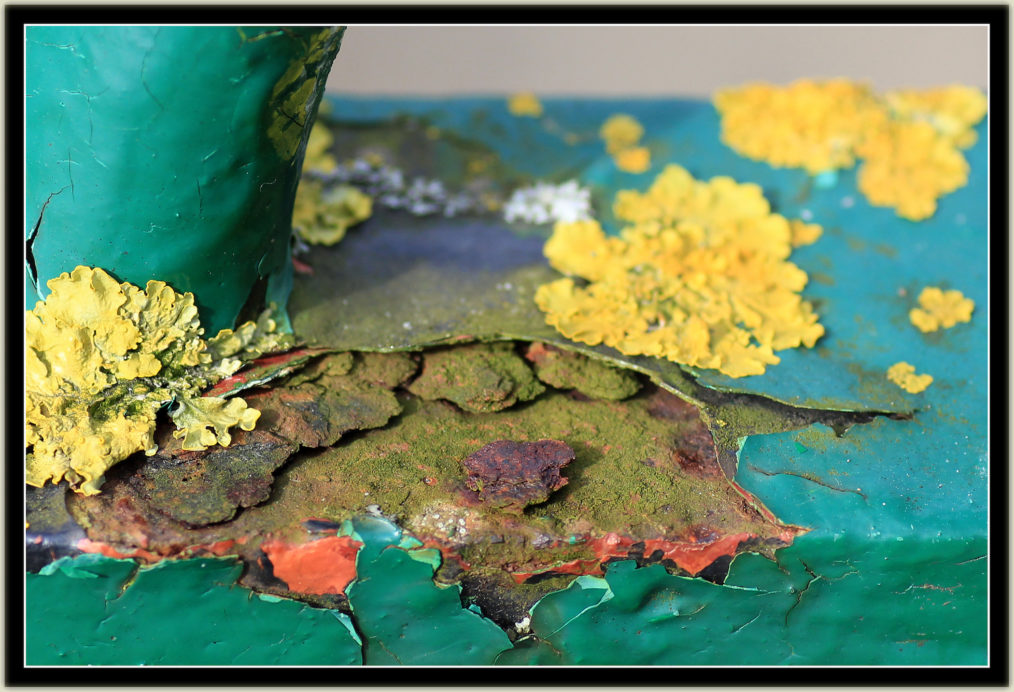

Photo credit: image by Mike Freedman, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0