Your rights or Our rights?

One of the things I enjoyed the most this year during Women’s marches and the March for Science is the amount of creativity and humour put into the banners. The reason why the banners are so important to activists is that they communicate who they are (“Who run the world? Girls”), what they stand for (“What do We Want? Evidence based science”) and what they believe in (“Women’s rights are Human rights”). You might ask who these banners are meant for: some are supposed to voice the disagreement to the authorities, and others are meant to motivate those who stayed at home to join the actions. In fact, one of the key goals of social movements is to increase the number of followers. What activists sometimes overlook is that not all members of the group they aim to represent (in this case women and scientists) share their beliefs. Hence, the messages the banners convey determine whether the movements will attract or chase away potential supporters.

“To attract supporters, a movement could align their values with greater societal goals”

In one of the chapters of my PhD-thesis, I investigated how social movements can mobilize those members of the groups they represent who do not share their beliefs. I specifically focused on how communicating values motivates engagement in collective action (Van Zomeren, 2013). Words like equality, justice and human rights are often used by social movements to attract followers, because these values should presumably matter to everyone. However, not all members of the same group have the same beliefs (e.g. not all women adopt feminist values), and talking about values people do not share can decrease perception of common ground (Kouzakova, Ellemers, Harinck, & Scheepers, 2012). Thus, one could argue that the best strategy is not to talk about values at all to avoid conflicts (Taüber, van Zomeren, & Kutlaca, 2014). Another potentially more successful strategy is to align the values of the movement with the greater societal goals (Kutlaca, van Zomeren, & Epstude, 2016).

For example, in recent years the Dutch student movement rallied against the governmental plans to impose fines on those who study longer and to change the student loans. The movement claimed that these measures go against an important value: they limit the access to education for poorer students. Surprisingly, not all students agreed with these protests, because they believed that welfare cuts were necessary in times of crisis. These students particularly disliked the messages that placed an additional emphasis on students as a group being deprived of important rights. However, when the movement’s message emphasized that education is important to all Dutch people, it opened a possibility for a movement’s cause to be seen as contributing to the wider society and therefore worthy of support.

“Surprisingly, not all students agreed with the protest against the change of student loans, because they believed that welfare cuts were necessary in times of crisis.”

So, what could movements do to increase their number of supporters? First of all, they should keep in mind that not all who belong to the same group share the same values. Second, they have to be flexible in communicating their goals, especially to an ideologically opposed group. Some banners may be seen as inappropriate (e.g., “Pussy Power”) and could even hurt the movement’s cause in the long run. In contrast, the messages that emphasize unity and explain why activists’ goals are important to everyone (“Progress in Science = Progress in Humanity”) may resonate even with those who may not necessarily share all their beliefs.

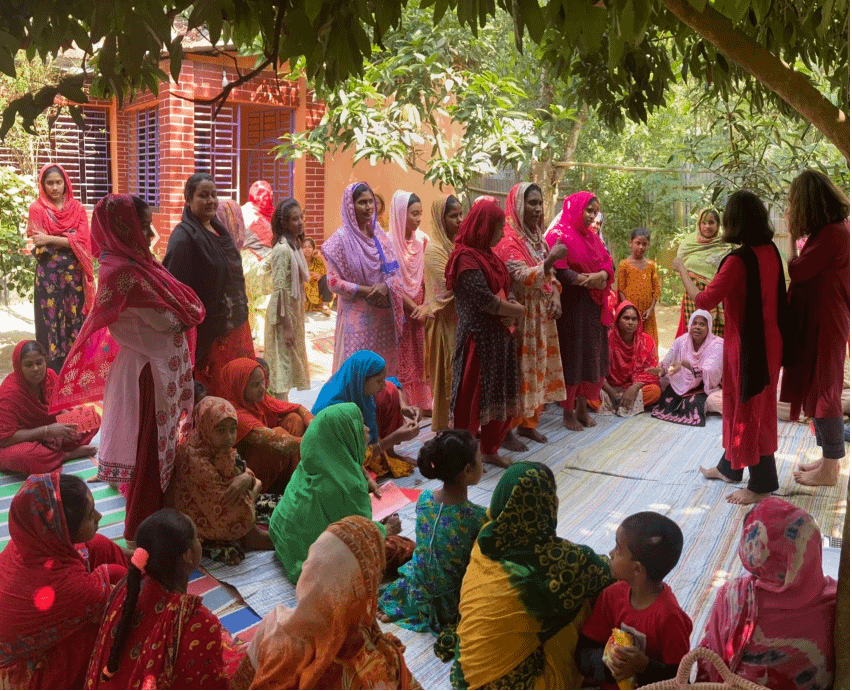

Note: Image by John Englart (TakVer) at Flickr.

References

Kutlaca, M., van Zomeren, M., & Epstude, K. (2016). Preaching to or beyond the choir: The politicizing effects of fitting value-identity communication in ideologically heterogeneous groups. Social Psychology, 47, 15-28. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000254

Kouzakova, M., Ellemers, N., Harinck, F., & Scheepers, D. (2012). The implications of value conflict: How disagreement on values affects self-involvement and perceived common ground. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 798-807. doi:10.1177/0146167211436320.

Täuber, S., van Zomeren, M., & Kutlaca, M. (2015). Should the moral core of climate issues be emphasized or downplayed in public discourse? Three ways to successfully manage the double-edged sword of moral communication. Climatic Change, 130, 453-464. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1200-6

Van Zomeren, M. (2013). Four core social-psychological motivations to undertake collective action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 378-388. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12031