The Perfect Memory

The common criticisms from professors about broad, superficially philosophical questions apply perfectly well to the title of this piece. What is a perfect memory? We may try to divide up the question and ask what both perfection, and memory are. We may ask whether memory refers to a memory of something or that reified agglomeration of things which we colloquially call our memory. Yet, in some contexts, it seems the idea of “perfect memory” has been pinned down. Psychologists employ a myriad tests to assess the memory capacity of individuals, this is generally then compared to a norm. Books, apps, magazines offering to “improve your memory” abound. If something can be improved, this implies a normative “better” direction. In this sense then, it is easy to imagine that at one end of the memory scale — the better end — is the ideal memory. The perfect memory.

… simply a chip behind your ear, and an elegant remote control and you can replay exactly and indefinitely, every moment of your life…

As far as I am aware, the vast majority of psychometrics relating to memory primarily measure something like capacity, accuracy and/or longevity of memory in its different forms. This would imply that the ideal memory, that which the exercises, games, puzzles, etc. will purportedly help you work towards, is one of infinite capacity and durability, and perfect accuracy. This is precisely the concept which is taken up in “The Entire History of You”, an episode of the television show Black Mirror (2011). In the creepily familiar world of this show, the perfect memory exists; simply a chip behind your ear, and an elegant remote control and you can replay exactly and indefinitely, every moment of your life. The creators of this show hint at more overt broader scale social implications, the very literal internalisation and universalisation of surveillance, but their focus is on the personal experience of this kind of perfect memory. Following the marriage of the main characters Liam and Ffion, we are led to reconsider whether such an accurate memory is indeed ideal. In the process we pass through questions about perspective, interpretation, morality, love…

The show asks us to consider the difference between a perfect recall of audio and visual memory, and the subjectivity associated with our “organic” memory. Whilst repeatedly poring over replays of everyday situations, Liam’s relationships to his memories change. After discovering that his wife lied to him on their first night together, Liam replays the video and laments “That was a nice night. Or used to be”. The memory recorded in his “grain” does not retain the feeling of being in that situation, the lense through which Liam experienced the world at that moment. The video and audio remain the same, yet the meaning of the memory has changed for him. The Liam that lived in that moment, is a different man to the Liam that reviews it. The memory itself, may have appeared to him previously as perfect, now it is tainted.

Following this, Liam becomes an image of an extreme kind of rumination. A kind with capabilities that allow him to minutely deconstruct and repeatedly review any episode in his life; we watch his obsessive investigation and its concurrent effects on his view of his wife, himself, and their relationship. Part of the poignancy of this show stems from its proximity to the current digital cultures. Already our ability to record and recall information via various mediums allows the easy and literally accurate reviewing of many aspects of our daily lives; emails, social media, photos, videos, digital calendars, google maps, wikipedia etc. It is not hard to find a story of a husband who caught his wife cheating through Facebook or Tinder, nor hard to imagine him demanding to listen to or read their correspondence, see pictures and the like. The public and concrete nature of these kinds of memories, as exemplified by the grains, opens up new possibilities for surveillance, of the self and others; yet the patterns of behaviour are familiar.

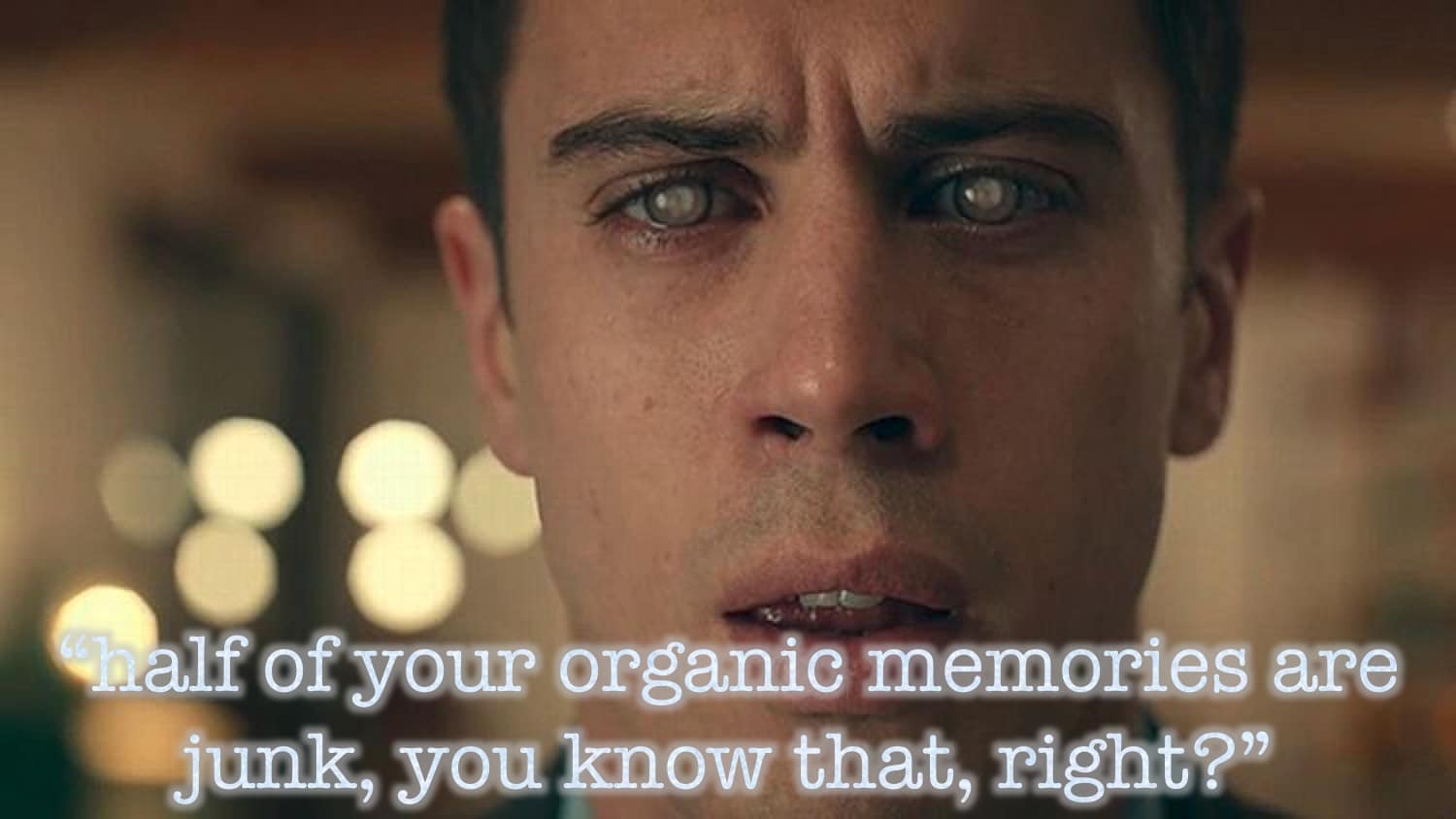

“Half the organic memories you have are junk. Just not trustworthy.”

“Half the organic memories you have are junk. Just not trustworthy.” declares Colleen at the dinner party (she works in grain development). Our organic memories are fallible in a sense; they are not an exact or unchangeable recollection of the situation, they do not sit, perfectly preserved, indefinitely. Colleen invokes Loftus’ “Lost in the Mall” (1995) study as testament to the superiority of the grain memory. We see however throughout the episode, that the digital memories which characters choose to replay are themselves dependent on their mood and situation and are easily isolated and removed from their original context. Liam makes this point about context when Ffion replays him directly after he calls her a bitch; “You can’t just edit off the word ‘sometimes’”. The grains are not simply a neutral technology, they are employed by individuals, integrated into human relations and emotions. We see beyond this, how images and sounds are only meaningful through a perspective, whether they are remembered organically or digitally they are still subject to interpretation, adjustment and selection.

Our relationship to technology and the increased capacities it brings affect our relationships with each other and our selves. We see Liam’s deployment of the perfection of his digital memory lead to the end of his marriage. We see him consumed by the minute details of the past. We see him at the end of the episode, in his now dark and derelict home, reviewing everyday situations with his wife and child, pining over that which he has lost. The pain of this perfection is too great and he gouges out his own memory. The creators of this show clearly see many potential negative consequences to the technology they invisage, yet these consequences come from access to a certain kind of truth or perfection. Our organic memories are inferior as regards capacity, accuracy and longevity, yet the feeling produced by this episode is that they are, despite (or likely because) of their imperfections, preferable to “grain” memories. The only character in the episode without a grain puts it simply, when asked why she did not get it replaced after it was cut out of her and stolen, “I’m just happier now”.

References

Amstrong, J. (Writer), Welsh, B. (Director). (2011). The Entire History of You [Television series episode]. In Brooker, C. & Jones, A. (Executive Producers), Black Mirror. Los Gatos, CA: Netflix.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25(12), 720-725. doi:10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-07

The post Perfect Memory was originally an assignment for the course Qualitative Research Methods, in the Masters on Reflecting in Psychology, at the University of Groningen.