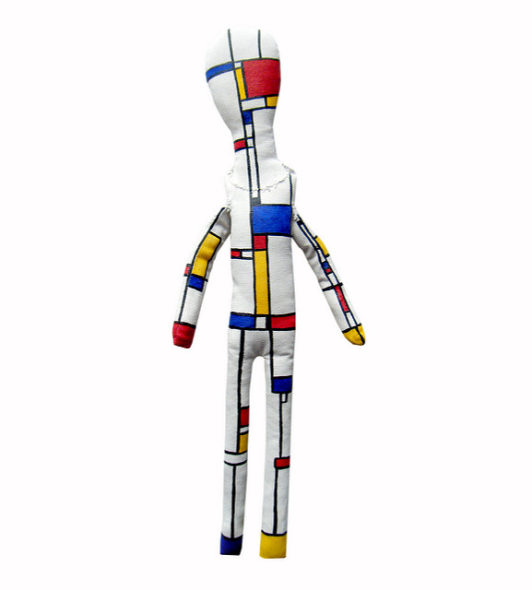

Mondriaan Moves:

How art can move the body.

This post was written together by Ralf Cox, Lisa-Maria van Klaveren and Muriël van der Laan.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of De Stijl, an artistic school that originated in the Netherlands. The painter and art theorist Piet Mondriaan (1872-1944) was one of De Stijls’s most iconic members. Mondriaan created a wide range of paintings of various kinds, of which the most famous ones are both loved and hated for their simplicity. His simple compositions, consisting only of red, yellow and blue rectangles, complemented with white areas and black lines, are world famous and count as a hallmark of Modernism. As the Dutch philosopher Jan Bor notes in his book Mondriaan Filosoof (2015), Mondriaan’s paintings have changed the way we perceive the world. Still, some people look at a Mondriaan and cannot help but think that even a child could have painted it. Many others, though, are deeply moved by his paintings. De Stijl‘s centennial celebration was one of the incentives for our exploration of how art is capable of moving people, literally as well as figuratively.

Art as an embodied experience

Our story starts with the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961), who explored the interaction between a spectator and a work of art. In his 1945 book Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty departs from the ruling notion of ‘être-au-monde’ (being-in-the-world), considering the body as a condition for the embodied experience the world. This means that we are continuously relating ourselves to our environment by means of perception and action. In the Causeries (1948), he appreciates art as a special form of creating these embodied experiences, because of the way it can influence how we perceive the world surrounding us.

“The goal of art is not to represent the world, but to capture how the world is experienced by the artist.”

Merleau-Ponty emphasizes that an artwork is not a representation of the world, but a world in itself. Accordingly, the goal of art is not to represent the world, but to capture how the world is experienced by the artist. The beholder re-experiences this, as it is mediated by the process of artistic expression. According to Merleau-Ponty, art is special because it is able to stir up the fixed meaning of the world over and over again. An artwork should provide us with a different viewpoint on the world. Think, for example, about the abstraction of the world by Mondriaan or the cubistic viewpoints employed by Picasso. Therefore, an artwork enables us to visualize a familiar or recognizable world in a completely new way. Following this, perceiving an artwork entails an embodied experience of the beholder as (s)he engages the artist’s subjective world (bodily) expressed in the artwork.

In connecting these ideas to Mondriaan’s paintings we follow Jan Bor. He proposes that Mondriaan’s art is about the creation of a ‘dynamic balance in movement’. For Mondriaan this creation of balance reveals how nature presents itself in contrasts. As art historian and former director of the Rijksmuseum, Wim Pijbes, during the opening of 100 years De Stijl notes: “Mondriaan was creating compositions without fixed symmetry and centre. He used four basic elements: primary colours, lines, rectangles and shapes, in different sizes. And he searched for new forms of artistic expression by moving these basic elements into new angles.” Thus, Mondriaan’s compositions trigger spectators to (re-)embody the dynamic balance in movement captured on canvas, literally moving them.

Bringing the museum into the laboratory

We decided to examine the moving quality of Mondriaans paintings in an experiment. Inspired by Merleau-Ponty we analyzed both the bodily movement as well as perceptual judgment of people while observing a painting. Participants looked at ten life-sized paintings by Piet Mondriaan and Jackson Pollock on a large screen (The Pollocks were added as contrast to the Mondriaans, a deliberate choice which will not be elaborated on in this blog post). Participants were standing on a Wii balance board to measure their postural sway, these small movements you make to keep you in dynamic balance. After each painting they used a tablet to rate its beauty and complexity and the extent to which they felt drawn-towards and moved-by it.

“Participants that literally leaned towards the painting, indicated to be figuratively more drawn-towards it.”

Preliminary results show a sophisticated interplay between painting, postural sway and appraisal. Interestingly, the way the participant’s bodies moved was very different for each painting. This means, that each painting influenced the participant’s movement in a specific way. Additionally, postural sway was related to scores of feeling moved-by and drawn-towards a painting. So, participants’ (literal) movements were associated to their (figurative) moved-by-ness. Participants that literally leaned towards the painting, indicated to be figuratively more drawn-towards it. Although this relation between figurative and literal movement may seem obvious, this has hardly been explored before. Therefore, further research into the embodied (art) experience is certainly worthwhile.

Bringing the laboratory into the museum

We are currently moving our ‘moving art’ study into the museum, since experiencing a real artwork is markedly different from looking at a picture on a screen. Two main differences are lighting and depth. First, the screen is a source of light itself, whereas an artwork receives indirect TL light or daylight. Second, a picture on the screen is flat, whereas the pasture of a real artwork adds much to the experience of it. In the coming months we will therefore perform the experiment with several of the amazing works of the permanent exposition of the Groninger museum. A real artwork will entail a purer (though subjective!) embodied experience, which will be closer to what the artist expressed. In addition, we are in contact with the Gemeentemuseum in Den Haag, hosting the main De Stijl exposition, to perform the experiment with actual Mondriaans.

Note: Image by MEDIODESCOCIDO, licenced by CC BY 2.0.

References

Bor, J. (2013). Mondriaan filosoof. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker.

Merleau-Ponty M. (2002). Phenomenology of Perception. (Tr: Colin Smith). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.