How to navigate the knowledge explosion in mental health research

Finding information on a particular topic in behavioral and social sciences can seem deceptively easy. On the one hand, we are provided with resources for easy access to information, the university pays for access to most journals, a large library books catalog, and immediately available electronic book collections, among others. On the other hand, one can be easily lost in that amount of literature, encountering conceptual heterogeneity, contradictory results, and a myriad of perspectives that lack consensus, making it challenging to study and understand certain phenomena. The amount of new information is growing at a never seen speed and we need tools and methods to effectively synthesize the scientific knowledge we produce. Below, I start with a reflection on traditional ways of knowledge summaries, followed by “unpopular” but effective examples of different ways of knowledge synthesis, and finish by presenting my research where I plan to develop a database containing all empirical evidence of daily stress and mental health research.

The amount of new information is growing at a never seen speed and we need tools and methods to effectively synthesize the scientific knowledge we produce.

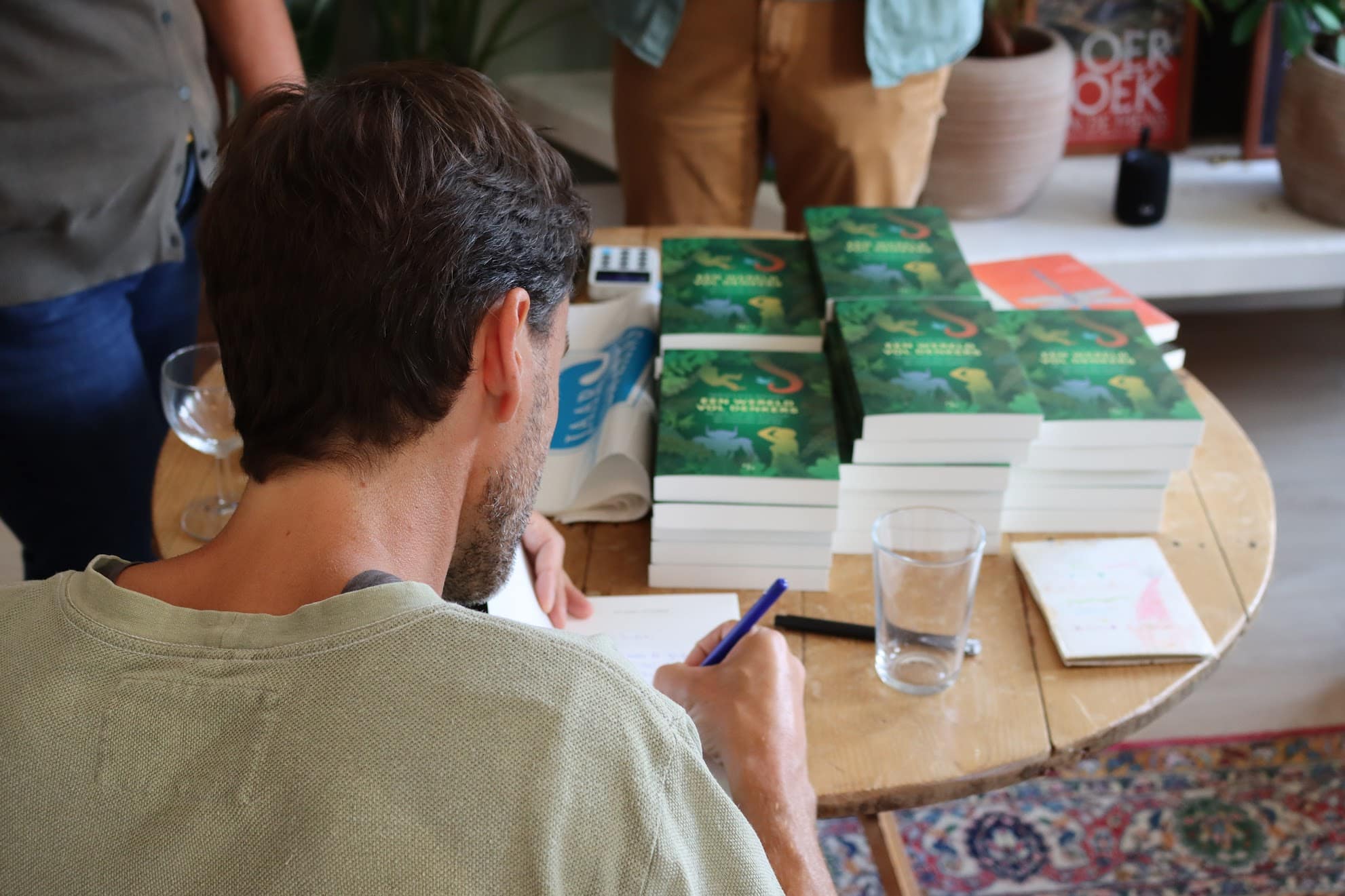

If we would like to know what is known about stress and depression, we can consult a few handbooks. However, books, as a traditional means of knowledge synthesis, rarely provide a comprehensive overview of the literature and purely rely on the author’s perspective and integrity. In addition, it seems this kind of knowledge summary is declining according to recent research. While the number of articles increased in the last decade by 36%, book publishing decreased by 23% –note that the number of researchers only increased by 5,4% in the US (Savage & Olejniczak, 2022). The race to find new statistical associations overshadows the effort directed at collecting and reflecting on existing evidence, which is vital for theory building (Eronen & Bringmann, 2021) revision of the formulated concepts (Bringmann et al., 2022), and consideration of the overall direction of the field.

The exponential growth of scientific publications (Bornmann et al., 2021; Fortunato et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023) calls for engaging in and optimizing the methods of knowledge synthesis. Accumulating scientific knowledge in an organized way can strengthen the field by providing access to large pieces of structured and reusable evidence on a particular topic. Currently, meta-analyses, followed by systematic reviews are considered the most reliable evidence synthesis (Ahn & Kang, 2018). However, they are time-consuming, have an “expiring date” (needs to be repeated to include new studies), and are limited to a very specific question.

The exponential growth of scientific publications (Bornmann et al., 2021; Fortunato et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023) calls for engaging in and optimizing the methods of knowledge synthesis.

As an alternative, the systematic review method can be used to build a database that would summarize and organize (part) the entire research field. Imagine that all published articles that study stress-depression relation would be found in one place and structurally organized according to some characteristics (e.g., variable measured, the setting of the study, the outcome) and which would be continuously updated with newly published studies. Such a database would be used to explore a variety of different questions in the form of meta-analysis or systematic review.

In fact, it is not a dream, but such databases already exist: the “Happiness Database” (https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/) or MetaPsy (https://www.metapsy.org/), the meta-analytic database of psychological treatment trials (Cuijpers et al., 2019, 2022). These databases are freely accessible and numerous reviews and reports are written using their content. Despite the substantial initial investment needed for establishing a comprehensive database, the potential benefits justify the cost by minimizing research waste (Cristea & Naudet, 2019; Ioannidis, 2016). Moreover, it provides opportunities to pinpoint knowledge gaps, map trends, inspire theory development, and facilitate conceptual revaluations.

Despite the substantial initial investment needed for establishing a comprehensive database, the potential benefits justify the cost by minimizing research waste (Cristea & Naudet, 2019; Ioannidis, 2016).

In my research, I am building a database on the topic of daily stress and mental health in the framework of the Stress-in-Action project (https://stress-in-action.nl/). Stress is a core concept surrounding physical and mental health research (e.g., in the etiology and maintenance of disorders and physical diseases; see Slavich & Auerbach, 2018). However, the 50 years of stress research were focused mainly on major stressful life events (e.g., death or a close one, losing the job) or chronic stressors (poverty, care burden, chronic disease), which offer an insufficient understanding of how or under what circumstances everyday stressful events (traffic jam, a fight with a friend, delayed delivery) contribute (or not) to the development of psychopathology and cardiometabolic disease.

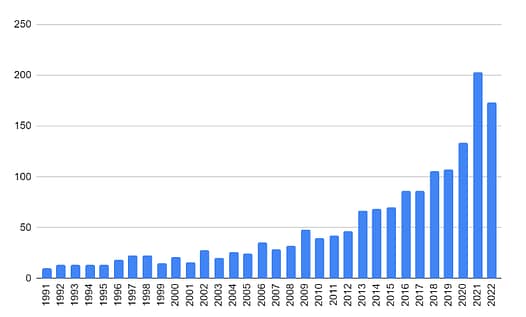

To deepen our understanding of the role of everyday stress in mental and cardiometabolic health first, we would need to summarize the existing empirical evidence on daily stress. We plan to select the studies that measure stressful events, psychological and physiological states (e.g., cognitions, cortisol levels), or behaviors (e.g., exercise, sleep) in daily life through ambulatory studies (e.g., ecologically momentary assessment, intensive longitudinal studies, daily diaries). These types of studies are gaining great popularity in mental health research and practice, as the number of published articles using intensive longitudinal studies on this topic increased four times in the last 10 years (see Figure 1; based on my bibliographic search in Web of Science). Apart from collecting and digesting all the evidence on possibly very heterogeneous studies surrounding daily life stress research, we are also particularly interested in observing how stress is operationalized, what are the (historical) trends, examining theoretical underpinning guiding these studies if any, and identifying the gaps.

To deepen our understanding of the role of everyday stress in mental and cardiometabolic health first, we would need to summarize the existing empirical evidence on daily stress.

Figure 1. Bibliographic search about daily stress and mental health in the Web of Science

Note. The graph represents the number of published articles (vertical axis) per year (horizontal axis).

But how we can achieve the proposed objectives if reviewing the literature takes so much time?

Working with large bibliographical records can be a challenging and laborious task (e.g., my initial search contains around 14.000 records). Hopefully, the advancements in AI tools make it possible. The researchers at Utrecht University developed a human-machine interaction tool, called ASReview (https://asreview.nl/), which has the potential to reduce the time of abstract screening by ~90% (Ferdinands et al., 2023). ASReview prioritizes the relevant abstracts based on questions of interest, leaving humans in charge of including the article, and updating its “working memory” with new information until no relevant records are left. By my estimate, we will be able to identify relevant articles in just two months. My ambition is to organize the selected articles based on the design of data collection, constructs measured, study population, and continuously update it with newly published studies making it a long-term project, and leaving a legacy for future generations of researchers. I hope that such initiatives showcase how with the help of AI software we can speed up the process of knowledge synthesis and make valuable contributions to the research community.

References

Ahn, E. J., & Kang, H. (2018). Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 71(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2018.71.2.103

Bornmann, L., Haunschild, R., & Mutz, R. (2021). Growth rates of modern science: a latent piecewise growth curve approach to model publication numbers from established and new literature databases. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00903-w

Bringmann, L. F., Elmer, T., & Eronen, M. I. (2022). Back to basics: The importance of conceptual clarification in psychological science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(4), 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221096485

Cristea, I. A., & Naudet, F. (2019). Increase value and reduce waste in research on psychological therapies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103479

Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Čihařová, M., Quero, S., Pineda, B. S., Muñoz, R. F., Struijs, S. Y., Llamas, J. A., & Figueroa, C. A. (2019). A meta-analytic database of randomised trials on psychotherapies for depression. https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/825c6

Cuijpers, P., Miguel, C., Papola, D., Harrer, M., & Karyotaki, E. (2022a). From living systematic reviews to meta-analytical research domains. Evidence-based Mental Health, 25(4), 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300509

Eronen, M. I., & Bringmann, L. F. (2021). The Theory Crisis in Psychology: How to move forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620970586

Ferdinands, G., Schram, R. D., De Bruin, J., Bagheri, A., Oberski, D. L., Tummers, L., Teijema, J. J., & Van De Schoot, R. (2023). Performance of active learning models for screening prioritization in systematic reviews: a simulation study into the Average Time to Discover relevant records. Systematic Reviews, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02257-7

Fortunato, S., Bergstrom, C. T., Börner, K., Evans, J. A., Helbing, D., Milojević, S., Petersen, A. M., Radicchi, F., Sinatra, R., Uzzi, B., Vespignani, A., Waltman, L., Wang, D., & Barabási, A. L. (2018). Science of science. Science, 359(6379). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0185

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2016). The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(3), 485–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12210

Savage, W. E., & Olejniczak, A. J. (2022). More journal articles and fewer books: Publication practices in the social sciences in the 2010’s. PLOS ONE, 17(2), e0263410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263410

Slavich, G. M., & Auerbach, R. P. (2018). Stress and its sequelae: Depression, suicide, inflammation, and physical illness. In American Psychological Association eBooks (pp. 375–402). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000064-016

Wang, F., Guo, J., & Yang, G. (2023). Study on positive psychology from 1999 to 2021: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1101157

Note: Featured image by Daniel Foster. Creative Commons License, Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 2.0).