How to develop a training to strengthen the position of women in Bangladesh?

This blog was collaboratively written by Madeline Langley, Farhana Tasnuva, and Nina Hansen.

Power isn’t divided equally — globally, gender still determines who gets more, usually leaving women with less. For example, in Rural Bangladesh many women have low power; many women face intimate partner violence and have little or no say in decisions about their household or their own health care (Kabeer, 2024; World Bank, 2022). To support women in these regions, we worked with several universities and an NGO to develop a social psychological women’s empowerment training.

Change is relational

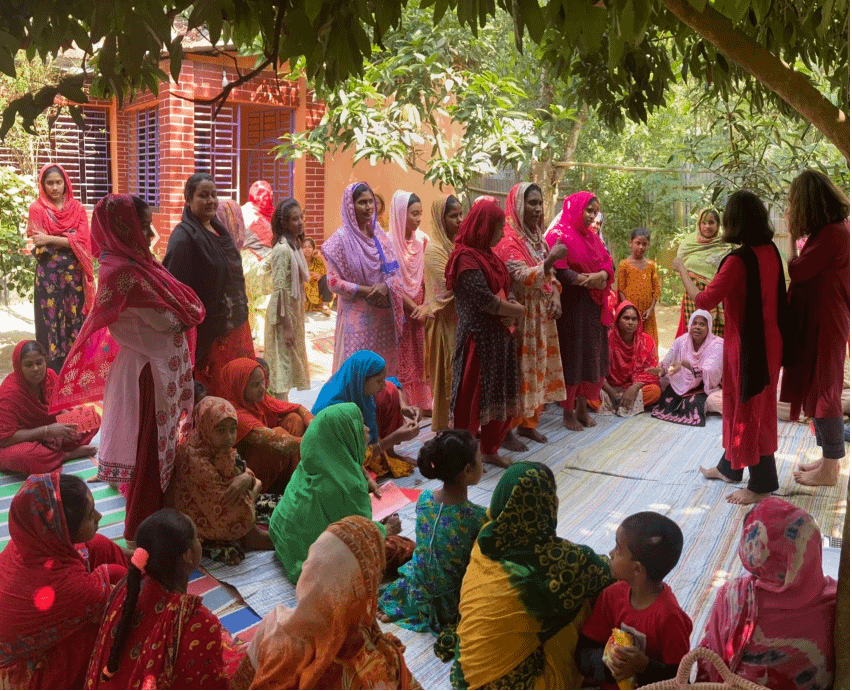

But how to design a women’s empowerment training? We started at the core: the people. We spoke to many women. We asked them about the challenges they face, what they want in life and what they need to get to a better position. To get a broader picture, we also spoke to their husbands, mothers-in-law, neighbours and community leaders. Through speaking to more than 250 people in rural villages in Bangladesh, we learnt a key lesson: women’s empowerment starts with social support. Women need social support from people in the community and support from family members, especially from their husbands.

“The husbands can give their support. Then it will be easy. Family support is very important. Women can achieve their goal if they get family support.”

– A woman participating in the interviews

But what stops women from getting this support? In the conversations, people explained that husbands can expect women to stay home and stay silent in household decision making. Women themselves may lack confidence to speak up or pursue goals. Additionally, women can hold the belief that it is wrong to provide support to other women or seek support from them.

The training program

Based on these lessons, we developed a training program of four sessions. We built the training to align with local learning styles and we used ‘wise intervention design’ (Walton & Wilson, 2018). This design draws on psychological exercises and techniques to invite people to rethink their mindsets and behaviours. You can imagine the training like this: five to ten women from the same community meet every two weeks to talk to each other and play games. The training provides a safe space for women, many of whom usually stay inside their house, to meet up and form friendships and support groups. In the last training session, women also bring their husbands. In this session, women and men discuss gender roles and play games centred around couple teamwork. Together, these training sessions aim to provide a fun opportunity to reflect and build relationships.

Learning from each other

Let’s be clear about what the training is not: it is not a place where a teacher comes to tell people how to live. Instead, the training aims to create a space where people can learn from each other. For example, one group discussed the benefits of helping each other and developed their own program in which they would take turns to teach each other how to sew. In other training sessions, high-status men explained to others why it is good to include wives in household decision making. These types of stories can help to change social norms. In other words, the training aims to provide a space where people are invited to think about topics related to women’s empowerment, and learn from each other’s experiences and opinions.

The training in action

Now, more than 500 men and women in rural villages in Bangladesh have participated in the training. To get an idea of what our training did, we followed some of the couples during the training and interviewed them about their experiences. Both women and men expressed that they really liked the training, they told us they gained a different way of thinking and learnt from their community members. They explained that the dynamics between the husband and wife had changed. For example, one husband was encouraged by other men to let his wife fulfil her dream to study. Before the training he was not keen, but he will now support his wife so that she can attend school.

Of course, these are self-reported, short-term impacts. A next step is to measure the impact of the training over a longer time span: we are working on a randomized controlled trial to find out more about the effectiveness and potential downsides of the training.

“Usually we look down upon our wives, and don’t care about them much. That day [the training day] we realized that we should care for our wives. I liked this discussion the most.”

– A husband speaking about the training he attended together with his wife.

To conclude, social change is complex. This four-session training program will not change the world. However, it can strengthen connections between people and invite them to think about women’s position. In this way, it may provide a starting point to support women in their growth and empowerment.

Image credit: photograph by the author team. In this picture you see us, Farhana Tasnuva and Madeline Langley, in the countryside in Bangladesh talking with women about their experiences and ideas.

References

Kabeer, N. (2024). Renegotiating patriarchy: gender, agency and the Bangladesh paradox. LSE Press.

Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125, 617–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000115

World Bank. (2022). Gender Data Portal. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/