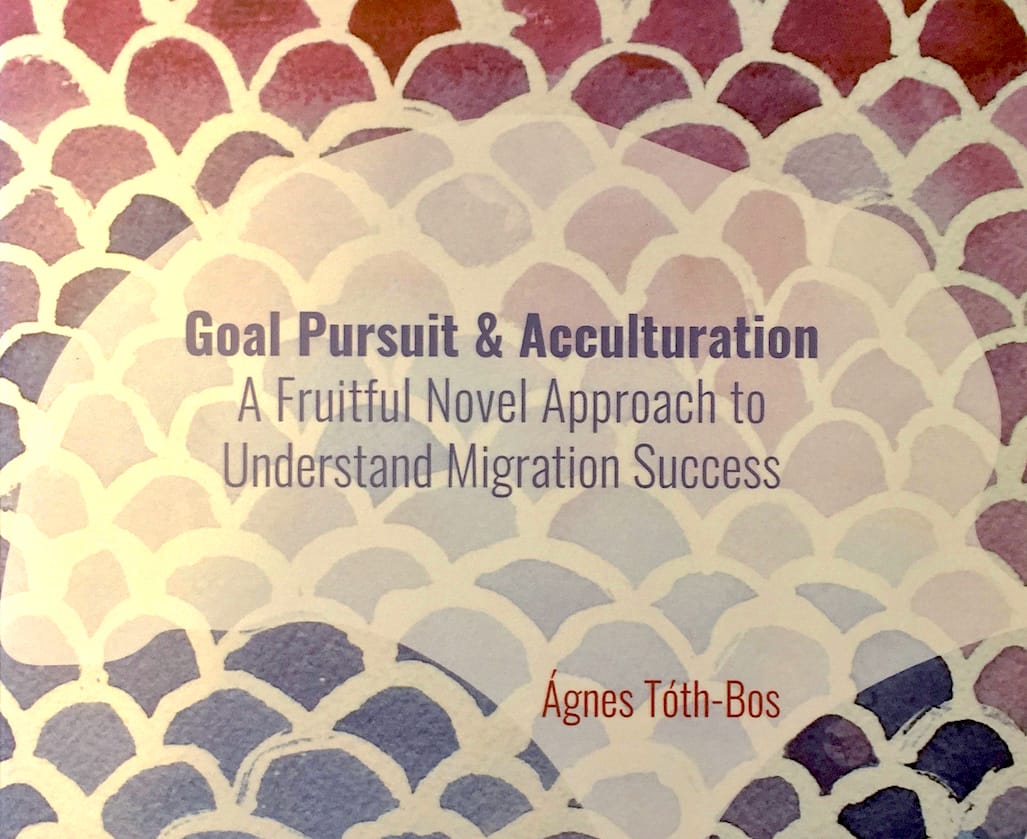

Goal pursuit and acculturation: A fruitful novel approach to understand migration success

When I first came to the Netherlands as a self-initiated migrant, I moved from home because I felt I had to make this sacrifice for my relationship with a Dutch man. Little did I know, back then, that such external motives might be detrimental for my well-being and my cultural adaptation (see Chirkov et al., 2007, 2008). At the time, I lacked the motivation to explore the new ways of living or learn the language, which otherwise would have given me a much better head start to thrive in a foreign country (see Pinto et al., 2012; Zimmermann et al., 2017). Indeed, my experience was far from pleasant: I was too closed off to realize the beauty of the culture and the environment, and struggled with discovering new opportunities to use my skills and time wisely.

My second attempt coming to the country was fueled by whole other reasons (although the same relationship): following an education that was closest to my interest, which challenged me professionally, and unlocked some inner strengths that took me a step closer to my professional dreams. So: same person in the same country, with a whole different set of goals and expectations, resulting in a very different cultural experience and openness to the host society. Through living up to my ambitions and realizing my goals, I grew to appreciate the Dutch culture, people, and landscape; I formed friendships, and began to be more perceptive to the new ways of living. This profound difference between my own experiences fueled my research interest and eventually inspired the main question of my PhD: How does goal pursuit impact the cultural adjustment and overall well-being of voluntary migrants? This was the question I decided to work on, under the supervision of Barbara Wisse and Klára Faragó.

Migration and Goal Pursuit

Migration is often set in motion when people want to achieve certain things that would be harder or impossible to achieve back home, or want to maximize their goal potentials. In the best-case scenario, migrants can choose when and where to migrate, and they are aware why they are doing it. They can change their mind and return where they came from, or they can go somewhere else. These circumstances (and choices) characterize self-initiated migration.

Migration affects people’s demands, opportunities, resources, and challenges, and it requires substantial goal adjustment and the reformulation of aspirations. Whereas some formerly existing goals may need to be put on hold (for example, having a promotion), other goals—which may not have been important in the home country—may become urgent (Kruglanski et al., 2002) upon migration. Despite this clear link between migration and goal pursuit processes, individual-level goal pursuit in relation to acculturation is largely understudied. The aim of my dissertation was to provide an overview of our current knowledge in the field of migrant motivation and goal pursuit, and to further explore the relationship between goal pursuit and adjustment. The thesis highlights migrants’ personal agency in the acculturation process, stressing that migrants should embrace their motivation and relentlessly work towards their goals to maximize their cultural adjustment.

So far, we know little about how migrants establish their goals, how they monitor their progress and under what circumstances they adjust them.

Reviewing the (scarce) literature

In my first chapter, I reviewed the literature on the current knowledge of how goal pursuit contributes to migration success, distinguishing between the three stages of migration (pre-migration, during migration and potential repatriation and onward migration) and between three different goal facets (content, structure, process; see Austin &Vancouver, 1996). Overall, it seems that research on the structure and process of goals in all stages of migration is relatively scarce. So far, we know little about how migrants establish their goals, how they monitor their progress and under what circumstances they adjust them. Research on goal content in the pre-migration and during migration stages seemed to be most developed, and indicated that various motives (e.g., focusing on economic, political or cultural aspects) may have an impact on migrants’ well-being and acculturation; however; the findings are not always consistent. Differences in the ‘type’ (international students, expats etc.) and the origin of migrants (their home country) seem to have effects on the relationship between goal content and migration outcomes. In addition, in line with the predictions of Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), goals that support autonomy (e.g., intrinsic goals) seems to be beneficial to adjustment for various groups of migrants.

Creating and testing a model

Building on these findings, in the following chapter I empirically tested the link between intrinsic goal pursuit (relationship-, health-, community-, and personal growth goals) and acculturation and life satisfaction among first-generation migrants. In two scenario experiments and two field studies, I found that the more migrants attain their intrinsic goals, the more acculturated they feel in the host country, which in turn makes them more satisfied with their lives and less depressed. I had also expected this relation to be particularly strong for highly important goals, but found only mixed support for this. It seems that migrants may benefit from intrinsic goal attainment, even if these goals are not particularly important to them.

In the next chapter, I focused on a very specific kind of goal: career goals. For migrants, being able to fulfill their career potential in the host country can be a real game changer in their cultural adjustment, making them feel like valued members of the host society (Wassermann et al, 2017). My longitudinal study with Hungarian migrants living in the Netherlands revealed that migrants were especially likely to succeed in attaining highly important career goals, which in turn made them feel more acculturated in the host country – further, this only turned out to be the case for migrants high in self-efficacy. Self-efficacious migrants may take more initiative, and are more likely to expand their networks, search for better opportunities etc. (see Ballout, 2009; Black et al, 1991). All of this suggests that self-efficacy is crucial in realizing work-related goals for people who have to face the difficulties of migration. It also seems that migrants’ work-related goals and the realization of these goals are indeed important for them to feel adjusted to the host country.

Self-efficacy is crucial in realizing work-related goals for people who have to face the difficulties of migration.

Finally, in the last chapter I set out to enrich our knowledge about human motivation by studying how the congruence between goal importance and goal attainment affects well-being; to do so, I used polynomial regression and response surface analysis (see Edwards, 2002). Distinguishing between intrinsic and extrinsic goals, and in line with the Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Kasser & Ryan, 1996), I found that the congruence between intrinsic goal attainment and importance positively predicted subjective well-being. For extrinsic goals, this was not the case. The findings underpin the unique impact of the specific goal content on well-being (not every kind of goal attainment has the same effect), and highlight the joint effect of goal attainment and importance on well-being: simply looking at goal attainment is not enough.

Acculturation is a consequence of successful goal pursuit, rather than a precondition.

Being a researcher and a migrant

While working on this subject, I found it particularly interesting to feel community with the respondents of my studies. It was intriguing to see how the experiences of other Hungarian and Central-European migrants in Western Europe resonated with my own experiences as a migrant. It seems that being able to realize our goals makes us, migrants, feel that we are successfully navigating the foreign cultural context, which in turn can help us feel positive and energetic, and shields us from negative thoughts. The message that is often portrayed by immigration policies worldwide is that “if you decide to come to our country, please first adjust, then you will have opportunities, then you can live up to your goals.” From my thesis a profoundly different picture emerges: If migrants feel that they can work on their personal goals, and they are assured that they can fulfill these goals in a changed context, then they will be more adjusted – both socio-culturally and emotionally. In other words, acculturation is a consequence of successful goal pursuit, rather than a precondition. This shift in perception could benefit policymakers, professionals working with migrants – and most certainly migrants themselves.

References

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338-375. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338

Ballout, H. I. (2009). Career commitment and career success: moderating role of self-efficacy. Career Development International, 14(7), 655-670. doi:10.1108/13620430911005708

Black, J. S., Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (1991). Toward a comprehensive model of international adjustment: An integration of multiple theoretical perspectives. The Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 291-317. doi:10.2307/258863

Chirkov, V. I., Safdar, S., de Guzman, de J., & Playford, K. (2008). Further examining the role motivation to study abroad plays in the adaptation of international students in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(5), 427-440. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.12.001

Chirkov, V., Vansteenkiste, M., Tao, R., & Lynch, M. (2007). The role of self-determined motivation and goals for study abroad in the adaptation of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(2), 199-222. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.03.002Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. doi:10.1207/ S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. doi:10.1207/ S15327965PLI1104_0

Edwards, J.R. (2002). Alternatives to difference scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In F. Drasgow & N. Schmitt (Eds.), Advances in measurement and data analysis (pp. 350–400). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 280–287. doi: 10.1177/0146167296223006

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal systems. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 34. (pp. 331–378). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80008-9

Pinto, L. H., Cabral-Cardoso, C., & Werther, W. B. Jr. (2012). Compelled to go abroad? Motives and outcomes of international assignments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(11), 2295-2314. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.610951.

Wassermann, M., Fujishiro, K., & Hoppe, A. (2017). The effect of perceived overqualification on job satisfaction and career satisfaction among immigrant: Does host national identity matter? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 61(2017), 77-87. doi:10.1016/j. ijintrel.2017.09.001

Zimmermann, J., Schubert, K., Bruder, M., & Hagemeyer, B. (2017). Why go the extra mile? A longitudinal study on sojourn goals and their impact on sojourners’ adaptation. International Journal of Psychology, 52(6), 425-435. doi:10.1002/ijop.12240