Collective protest in the eyes of the advantaged… a tricky issue

On January 13th 2019, the razorblade company Gillette released an advertisement in which it radically tweaked its 30-year-old slogan. “The best a man can get” became “the best a man can be”. The ad initially showed young boys bullying other boys and men objectifying women, while news about the #MeToo movement ran in the background. “Boys will be boys” was the message from the protagonists of the first part of the ad. It later showed men speaking up against other men who exhibited prototypical behaviors reflecting toxic masculinity, such as wolf-whistling women on the street or fighting among themselves.

On YouTube, the ad has more than 30.8 million views. Publicity stunt aside, this ad was one of the most disliked YouTube videos ever, with 1.5 million “dislikes” and only half as many “likes”. The comments section largely shows negative reactions to this anti-harassment ad (after a full 15 minutes of scrolling I could still not find a positive one). This is surprising, to say the least… One would think that nowadays, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, openly criticizing any initiative trying to make a point against sexual harassment and bullying would be highly politically incorrect…

“One would think that in the wake of the #MeToo movement, openly criticizing any initiative trying to make a point against sexual harassment and bullying would be highly politically incorrect…”

But what surprises more is that the negative responses occur despite the fact that the ad does not portray ALL men as perverts or bullies. The ad does not present women pointing the finger at men. It actually does quite the opposite by showing a series of examples of men speaking up against harassment by other men.

So why did the ad trigger such a massive and instantaneous knee-jerk negative reaction among men? And are all men equally likely to show this reaction or are we looking at a “specific” type of men?

I have been interested in understanding how collective action movements that protest against inequality, such as #MeToo (or Black Lives Matter or the Yellow Vests), are perceived by those who do not directly benefit from the collective action. To understand when social change is likely to occur as a result of collective action, we need to understand how ‘audiences’ receive these actions.

The main goal of the movements is to raise awareness of an unfair state-of-affairs among the audiences who witness it. Indeed, social media have become such an important tool for collective action because it is played out on a “social stage”.

In this sense, we can imagine that the advantaged are the ones who came to see the play without really wanting to buy the ticket or knowing what it was about. In other words, among the audiences who witness collective action, there are members of advantaged groups (such as men in the case of #MeToo), who may show resistance to social change.

“Advantaged groups may resist social change because they may lose their status and resources, and because the protest implies that their advantages is unfair.”

Two main reasons are at the source of this resistance: the prospective loss of status and resources (i.e., privilege) and the fact that accepting collective protest implies accepting that one’s group benefits from unfair advantage, “unfair” being the operative word.

In my recent research (Teixeira, Spears, & Yzerbyt, 2019) I tried to shed light on when, why and by whom collective protest is most likely to create resistance. To do so, in a series of 10 experiments, we showed advantaged group members examples of collective action that took different forms. Specifically, we varied the extent to which the protest followed the “social norms of protest”. Democratic societies are open to the possibility of protest but have clear rules (even laws) about how it should be done. These normative collective actions generally involve petitions or approved demonstrations and strikes, among others. However, protesting groups do not always follow the rules of what is seen as a legitimate way to protest by the general society. A recent example is the Extinction Rebellion movement triggered by Greta Thunberg, a Swedish high-school student who went “on strike” from school over her own government’s climate inaction. Extinction Rebellion is a peaceful civil disobedience movement that has undertaken actions such as the blocking of roads and streets or having activists glue themselves to buildings. These actions are called non-normative collective actions. The first such actions, conducted on the 17th of November 2018 in London, caused major traffic disruptions and led to 70 arrests.

In our experiments, half of our (advantaged) participants were asked to indicate their support for a normative protest and the other half for a non-normative one. We conducted these studies in the context of collective action against gender and ethnic inequality in four different countries.

“Advantaged groups show very low levels of support for collective action”

Generally, we found that advantaged groups show very low levels of support for the collective action. Interestingly, support for protest was even lower among the advantaged participants who were faced with non-normative protest and who reported being highly committed to their advantaged identity. This was because non-normative protest (compared to normative) is seen as questioning the moral social image of the advantaged group more. In other words, the fact that disadvantaged groups use “desperate measures” to attract attention to their grievances communicates the message to the general society that inequality is indeed unfair and that the advantaged are somehow to blame for the situation. Even though all participants in our studies agreed that this is indeed the message conveyed by non-normative protest, only the ones more committed to the identity of the advantaged group were sensitive to this threat to their group’s image and, as result, refused to support protest by the disadvantaged.

“When disadvantaged groups use “desperate measures” to attract attention to their grievances, this communicates to the general society that inequality is indeed unfair and that the advantaged are somehow to blame for the situation.”

Returning to the #MeToo movement… the Gillette ad apparently questions a “traditional” image of masculinity, by urging men to change and become someone else. According to our research, this should be especially threatening to men who are committed to a masculine identity, and lead to less support for inequality reduction among them (independently of whether they are the perpetrators of the behaviors being criticized!).

At the same time, our research showed that advantaged group members who were not highly committed to the advantaged identity did not show these negative reactions. Thus, according to our research, the good news for inequality reduction is that threats to the advantaged group’s image do not lead to less support among all advantaged group members. The next step for research is therefore to understand better how to motivate this (potentially) “silent majority” to speak up…

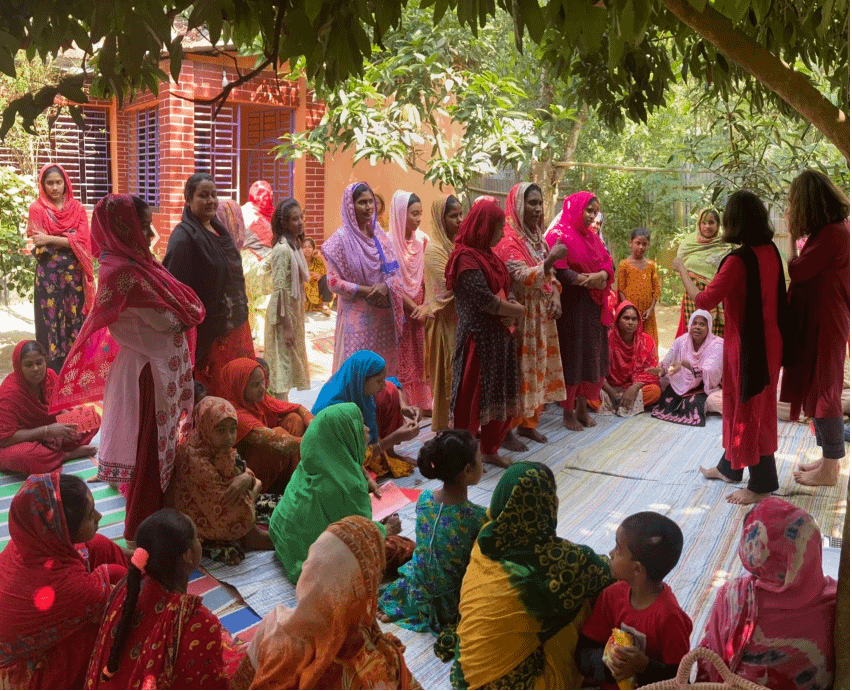

NOTE. Image by Catia Teixeira.

References

Teixeira, C. P., Spears, R., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2019). Is Martin Luther King or Malcolm X the more acceptable face of protest? High-status groups’ reactions to low-status groups’ collective action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000195