Book Review: The Inkblots by Damion Searls

“Take the official Rorschach Ink Blot test to see if you are crazy”, is the title of the first video that comes up when you type Rorschach Test on YouTube. In the 2006 music video featuring animated inkblots morphing into disturbing images that turn into people, Gnarls Barkley sings “Maybe I’m crazy. Maybe you’re crazy. Maybe we’re crazy. Probably.” The Rorschach test appears to be synonymous with insanity, yet people are quickly dismissive of its validity as a diagnostic instrument.

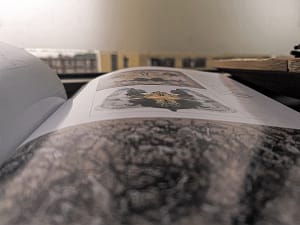

“The Rorschach test uses ten and only ten inkblots, originally created by Hermann Rorschach. Whatever else they are, they are the ten most interpreted and analysed paintings of the twentieth century.” writes Damion Searls in his recently published account of the Swiss psychiatrist and his iconic test, The Inkblots, which is part biography and part historical narrative.

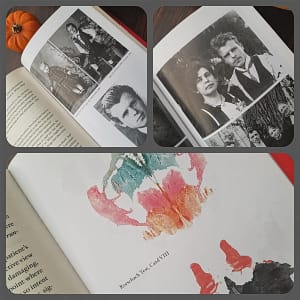

“If you think he looks like Brad Pitt, maybe with a little Robert Redford thrown in, you are not the first”

For nearly a century, Hermann Rorschach’s symmetrical inkblots have been placed in front of people as a means to a “mental X-ray” allowing a glimpse into their inner self. Damion Searls’ fascination with the test is palpable as he dives into unpublished material of Rorschach’s correspondence, family photographs and drawings, and offers a glimpse into the life of the man behind the test. With such negative preconceptions surrounding his life’s work, would people be surprised to know that Hermann Rorschach was a handsome, highly intelligent and deeply caring man with a happy childhood?

Rorschach was born in Switzerland in 1884, and his fascination with klexography, the art of making images from inkblots, was apparent to his school friends, earning him the nickname Klex (inkblot). Perhaps the greatest influence in Hermann’s life was his father, Ulrich, who studied art in Germany and not only acted as his mentor, urging him to follow his artistic inclinations, but also introduced Hermann to theories on colour, form and space and how they relate to human psychology.

Unfortunately, tragedy struck the Rorschach family twice, first when Hermann’s mother died from diabetes and later when his father’s unknown neurological condition, presumably Parkinson’s disease, left him and his siblings orphans. Hermann eagerly became a parental figure to his two siblings and responsibly helped their cold and distant stepmother raise them. Despite their constant struggle with money, Rorschach decided to leave his family and live a spartan life in Zurich as a medical student. Under the influence of Paul Eugen Bleuler, who stood in the middle of the opposing Jungian and Freudian schools of psychoanalysis, Hermann began working on a simultaneously structured and unstructured test, based on specific prompts that allowed for free association while also reaching the unconscious mind, as in hypnosis, and could also be taken in one session offering a “unified picture”. After multiple drafts with blots, he finally settled on the ten drawings still in use today.

“In a way it is a beautiful thing, to leave in the middle of life, but it is bitter.“

In The Inkblots, Damion Searls concentrates on Rorschach’s background in art and the influences of his time, working together to allow Hermann to come up with his iconic test. The author’s extensive research and eagerness to integrate the entirety of the material he gathered in a comprehensive volume, is also the book’s flaw, as the detailed text becomes tedious and loses a reader eager to experience a more engaging story. These more engaging scenes do make an appearance, as when Searls narrates the hours before and after Rorschach’s death caused by a burst appendix. It is difficult not to feel moved by the tragedy of Rorschach’s final hours, as the author writes Hermann’s last words to his wife:

“In a way it is a beautiful thing, to leave in the middle of life, but it is bitter.”

Apart from the occasionally monotonous and dragging narrative, Searls sporadically presents cases of people who took the Rorschach test with fascinating results. One of these cases strongly argues against both the computerised and the blind-analysis method of scoring the Rorschach. This case was of Hermann Göring, one of the most powerful Nazi leaders. Göring took the Rorschach test during the Nuremberg trial. Gustav Gilbert scored his test and when asked what it had showed, he told Göring:

“Do you remember the card with the red spot? Well, morbid neurotics often hesitate over the card and then say there’s blood on it. You hesitated, but you didn’t call it blood. You tried to flick it off with your finger, as though you thought you could wipe away the blood with a little gesture…you did the same thing during the war too, drugging the atrocities out of your mind. You didn’t have the courage to face it. This is your guilt…You are a moral coward.”

This and more cases of people’s personalities presented and analysed using the inkblots compile the book’s most captivating parts. For years since its conception, the scientific community has argued over the test’s credibility. The question remains: “Does the Rorschach test work?” The author adds fuel to the fire with a few fascinating examples showcasing people whose lives have been affected by a test that largely still remains a mystery. These cases argue that the Rorschach does work and when it does, it can be more insightful than the most commonly used personality tests.

The Inkblots is a thorough account of Hermann Rorschach’s life and a meticulous narrative of the test’s history, sprinkled with intriguing reports of the test’s power as exhibited in real life vignettes. In the final chapter, Searls finds a practicing psychologist specialising in the Rorschach test, and takes the test himself. He writes: “Ferris (the psychologist) told me I was a little obsessive“. His obsession to details is certainly evident in his work, but in the end, one can naught but appreciate the author’s humour in choosing to share this one personality characteristic that perfectly reflects both the strength and weakness of his book.