For much of history, pupil size changes were thought to be nothing more than a basic reflex. Bright light? The pupils constrict. Darkness? The pupils dilate. This function seemed obvious: pupils regulate the amount of light that enters our eyes. But the past decade of research has revealed a far more fascinating truth: pupils are not just passive responders to light, but are tiny windows into our minds. Pupils don’t just reflect the brightness around us, but also what we’re paying attention to and what’s unfolding in our minds.

A study by Mathôt et al. (2013) was one of the first studies to show this. In their experiment, participants viewed a screen divided vertically into two halves—one bright, the other dark—while fixating on the center. They were instructed to covertly attend to one of the sides. If you’re wondering what “covertly attending” means, think of it like when subtly checking out your crush across the bar—fully tuned in, but without moving your gaze. In this experiment, participants kept their eyes fixed at the center while mentally focusing on either the bright or dark side. Remarkably, the results revealed something astonishing: the participants’ pupils responded as if they were directly looking at something bright or dark, even though they were only shifting their attention on a screen displaying both bright and dark areas.

“What happens to our pupils when we attend to what we can no longer see?”

This finding stuck with me, sparking a deep curiosity: How can higher cognitive processes, like attention, influence something we’ve long thought of as a reflex such as pupil size? One PhD later, I’ve discovered that pupil size is influenced by various cognitive processes: attention (Vilotijević & Mathôt, 2024b), working memory (Hustá et al., 2019), and mental imagery (Laeng & Sulutvedt, 2014) can all cause our pupils to constrict or dilate without any change in physical light. The pupil appears to be doing far more than the basic light adaptation we believed. In my work, I argue that these cognitively driven effects might be functional, and that pupil size is fine-tuning vision to match behavioral demands (Vilotijević & Mathôt, 2024a).

But asking about the function of cognitively driven pupil-size changes is one thing. In other studies, I dove deeper into how these changes occur in the first place. In particular, I wondered: Are they tied to our conscious subjective perception of what we see? If we strip away that perception, would these cognitively driven changes in pupil size persist, or would they vanish along with the perception of the stimuli? In other words: what happens to our pupils when we attend to what we can no longer see?

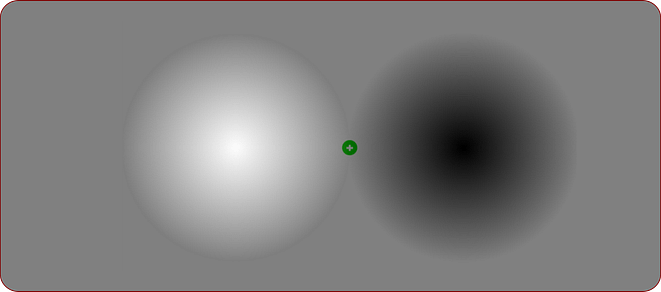

To answer this question, we (Vilotijević & Mathôt, 2024c) used a similar setup to the Mathôt et al. (2013) study described above, presenting a bright circle on one side of the screen and a dark circle on the other. However, this time, we added a twist: the circles had blurry edges, making them appear fuzzy. We did this because when people stare at the screen with fuzzy circles like this, the circles gradually seem to fade away, leaving them ‘unseen’ by the mind. You can try it out yourself using the screenshot below from our experiment! Fixate on the green cross, don’t move your eyes, and try to minimize blinking. You will notice that in a couple of seconds, the fuzzy circles will fade away from your perceptual awareness, and it will seem as if you’re looking at a gray screen.

This phenomenon we call perceptual fading. It occurs due to a process called neural adaptation, where neurons in the visual system become unresponsive to stimuli that are static or unchanging. This effectively causes them to disappear from conscious perception. Blinking or moving your eyes would “refresh” your neural activity, which makes the stimuli reappear.

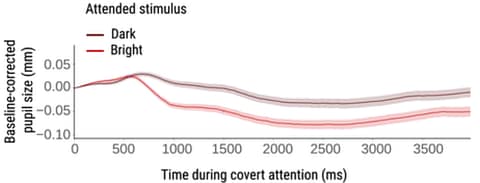

So, we asked participants to do the same thing that you just did, while covertly attending to either the bright or the dark circle. This all to answer the big question: once the circles fade from participants’ perceptual awareness, will their pupils respond to what they see (what’s actually presented on the screen) or to what they perceive (their conscious experience of what’s presented on the screen)?

We discovered that even though participants experienced perceptual fading of the circles, their pupils continued to respond to what was actually shown on the screen—seeing the unseen! This finding introduces a fascinating piece of the puzzle on how pupil size, attention, light, and perception are intertwined. We already knew that attending to bright things has a similar effect on the pupil as seeing (and perceiving) bright things, but our research shows that this attention effect is driven by what we see, more so than by what we perceive. In a sense, our participants’ pupils revealed more about where their attention went than their own perceptual experience.

So, next time you’re at a bar covertly checking out your crush, remember: even if you think you’re being subtle, your pupils know better. They quietly broadcast what’s on your mind, and if they start rapidly dilating, they might even be giving away your heart—but that’s a story for another time. Don’t get too sentimental, though—just like with perceptual fading, reality can get blurry. Sometimes, all it takes is a blink to refresh things, and suddenly, what seemed unseen might come into focus and change your perception entirely.