Reading fast and slow: The trust in databases problem

There’s too much to read, no matter your field. If you are interested in a hot topic, it’s worse: there’s more being published than you would ever have time to read even if you had already read all of the old stuff. So you fall further behind every day.

You read too slowly. Or too closely. You are too imprecise in choosing what to read, given the challenge of keeping up with the literature. But also too narrow, because different authors say the same things using different words.

In short: it’s impossible. The task can’t be done well and completely. Or can it?

The joy of having access to a manageable collection via GIPHY

In the spirit of working smarter, rather than harder, you might seek to use database-enabled collections of article full-text like that provided by the American Psychological Association’s PsycInfo (and PsycArticles) to enable the “distant reading” of thousands of articles in a single glance (following Moretti, 1994-2009/2013). Indeed, Chris Green and I did exactly that for the early history of psychology, looking for language similarities and identifying previously-invisible historical groups solely by noting differences in the published discourse (Green, Feinerer, & Burman, 2013, 2014, 2015a, 2015b). But this isn’t really a good solution unless you’re only interested in the old stuff.

The problem is that you can’t get the full-text for recently-copyrighted works. Not easily. Or at least not systematically and in a way that can be trusted to be complete. We tried. Heroic efforts were made, even from within the relevant governance structures.

My five years of service as an advisor to PsycInfo didn’t help get us access to what we needed. Nor did my three years as liaison to the Publications and Communications Board, which governs the production and dissemination of all APA texts (both print and electronic). Or Chris’ presidency of an APA division. That’s why having access to a good repository of texts is at the top of the hierarchy of digital needs (Green, 2016). But because that doesn’t exist in the way we want or need, in psychology or psychiatry, you have to approach the goal indirectly.

Some researchers use titles and abstracts as approximations of the underlying full-text. This can yield powerful and interesting insights (e.g., Flis & van Eck, 2018). But it isn’t perfect. Especially because these short descriptions are rarely a perfect representation of what the article actually says; not when you consider the difference between what the author intended and how a later distant-reader might engage with their work.

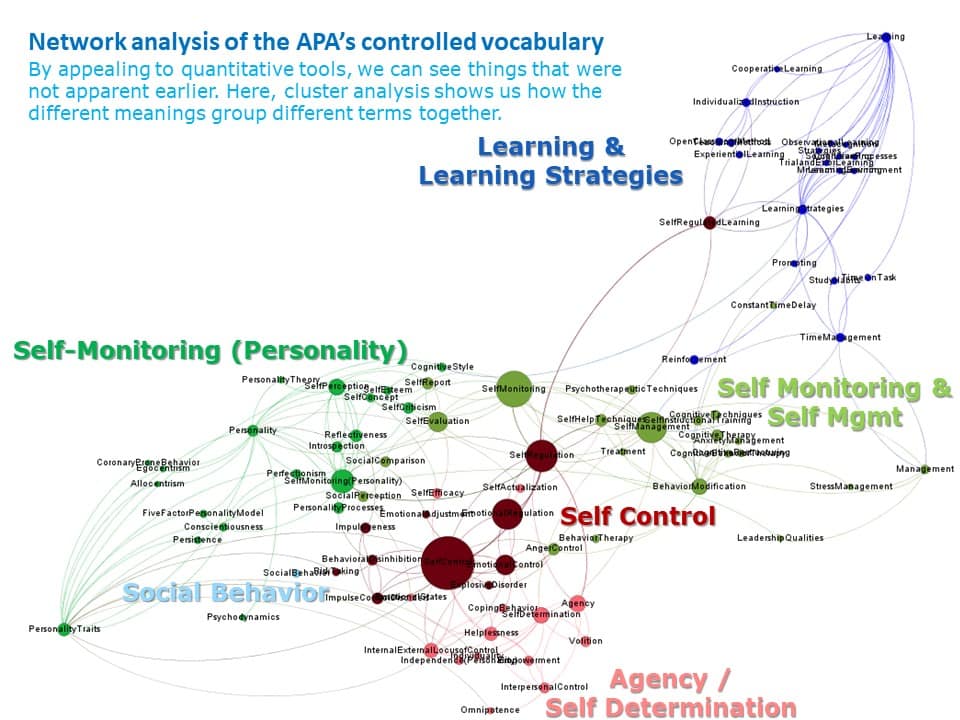

A map of what it’s possible to mean when you say “self-regulation” to a psychologist, from my 2015 article in Child Development

To accommodate all of the issues that we knew about at the time, I undertook an analysis of the discipline’s “controlled vocabulary” (Burman, Green, & Shanker, 2015). This approach illustrates the relations between terms that have been defined so you can find what you’re looking-for even if you don’t know the words used by the authors in explaining their work. And that seemed to me to be a way forward that side-stepped many of the barriers and constraints we encountered in thinking about how to bring historical digital methods into the present.

Using a controlled vocabulary enables access to current research – without full-text – by taking advantage of the system of fuzzy-matching that the founders of the APA created over a century ago with their dictionary programme. So it allows you to capture what scholars are talking about in their published work even when they don’t use your words.

I’ve since been working to extend those methods. It turned out, however, that even this simplification was more complicated than I expected: there have been uncontrolled changes over time not only in the controlled vocabulary, but also in how it has been applied as meta-data (described by Burman, 2018b). So it’s taking a lot longer to build something useful – in the way you would need for conducting systematic reviews, or even just following a concept through time – than I had hoped.

The main problem is that everything you might do, and every method you might use, comes with limitations that need to be understood before you can trust what your review says you’ve found. This happens even when you use a supposedly trusted system, like the curated cited references that underlie Journal Impact Factors (Burman, 2018d). As a result, it’s better to think of these methods as being directed toward asking better questions than toward providing answers directly (Burman, 2018a).

A slide from my presentation in Copenhagen

Or to put it another way: these digital tools that help speed reading are complementary to normal methods, but not replacements for them (Green, 2018). You still have to be careful and critical, and you have to investigate what it is you think you’ve found before you start applying any insights arising.

More concretely: Chris’ study of how statistics have been reported in Canadian psychological journals found that the digitizing process sometimes reverses the signs in the reported findings. So comparing the text that computers read to the text that humans read, findings flip from “significant” to “non-significant.” And this is on top of the already-known set of common and well-documented stats problems, like when reported p-values don’t match corresponding test statistics like F, t, and χ² (Green et al., 2018; also Nuijten, Hartgerink, van Assen, Epskamp, & Wicherts 2016). That’s a serious issue if what you want to do is use computers to read lots of studies for you and then summarize the results in a way that you can trust enough to use in research or practice.

I described these issues collectively as the “trust in databases problem,” first at the meeting of the European Society for the History of the Human Sciences (here in Groningen) and then again in an expanded way at the meeting of the International Society for Theoretical Psychology in Copenhagen (Burman, 2018c, 2019). I thought this description fit nicely, using language these audiences would appreciate: it riffed on the title of Ted Porter’s (1995) now-classic book about the use and misuse of statistics in science and government (viz. “Trust in numbers”). To support the project, I also developed and submitted some grant proposals that would take advantage of the recognition of all these concerns to construct a more transparent and trustworthy tool.

This garnered good support initially: Wisnu Wiradhany and I won a small grant from the Heymans Symposium to advance the project a step further. We then ran into a problem with author-name disambiguation that we’re still working to address, because ORCIDs – which are basically DOIs for names – haven’t been implemented yet at the database level to afford a controlled vocabulary of authors. (The name Paul van Geert is not identical at the system level with P. van Geert or P. L. C. van Geert, and this lack of shared identity increases the complexity of the results in an artificial and misleading way.) But fixing this problem also needs to be done in as simple a way as possible because the current systems that do this all use AIs, and you can’t deconstruct or even understand their decisions. They’re black boxes. And the big granting agencies haven’t liked hearing that.

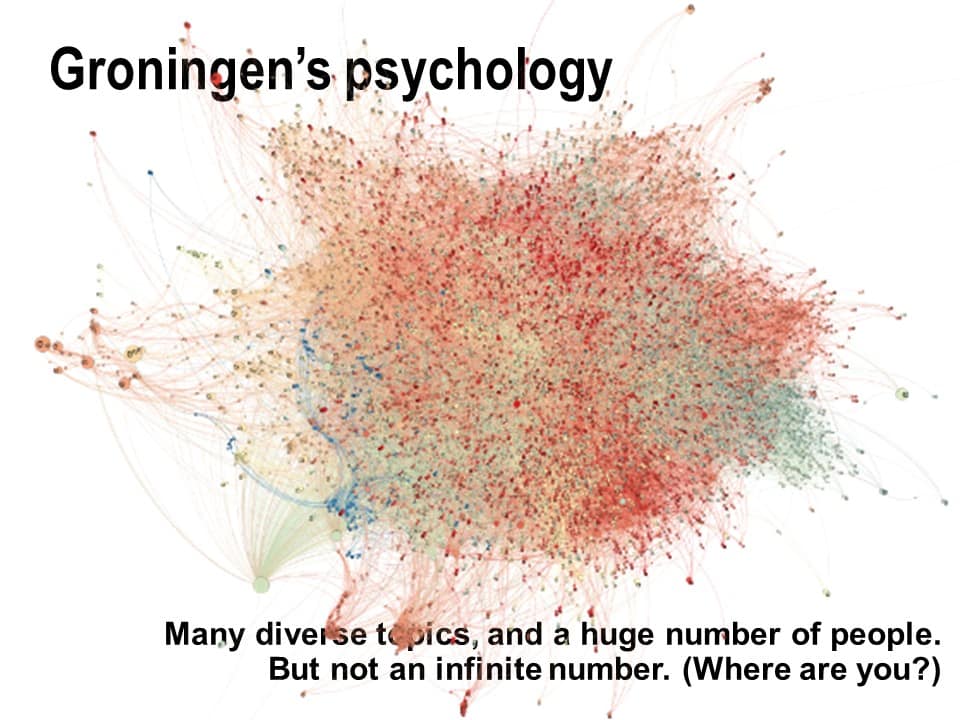

An unpublished network analysis of all Groningen-based, English-language psychological journal publishing (2014-2018) shows identifiable clusters of individual scholars unified by shared interests. But how much of this diversity is a function of the tool, rather than of reality? Which nodes ought to be grouped because they refer to the same person in different ways? (And who got left out?)

This transparency is important if you want to do more than ask interesting questions (cf. Green, 2000). Here in Europe, it’s also required now for AI-driven tools (see O’Brien, 2020). But because of the various unevennesses that Chris and I have found, you should want to do it transparently even if that weren’t required: you can’t rely on the systems themselves, as they exist today, and be certain that what they’ve reported is identical with what you would find if you looked more slowly, more carefully, and more closely.

In short: you can’t just run a search – or an AI – on the infrastructure we’ve got in psychology (or psychiatry) and trust the results. I suspect it would even be unethical to do so if your goal were to derive solutions to be used directly with vulnerable populations. As an aid to scholarship, however, these tools are very powerful. You could certainly use variations of what Chris and I have done to ask better questions more easily. But there still aren’t any “easy answers” here; no low-hanging fruit to be plucked and enjoyed fresh off the vine.

As is often the case with new ideas, still more research is required. However, with the rising popularity of these tools, a critical approach is also more important than ever: if you want to read more quickly, you first have to think carefully about what you will take away from the text.

References

Burman, J. T. (2018a). Digital methods can help you…: If you’re careful, critical, and not historiographically naïve. History of Psychology, 21(4), 297-301. doi: 10.1037/hop0000112

Burman, J. T. (2018b). Through the looking-glass: PsycINFO as an historical archive of trends in psychology. History of Psychology, 21(4), 302-333. doi: 10.1037/hop0000082

Burman, J. T. (2018c). Trust in databases: Reflections on digital history of psychology. Paper presented at the European Society for the History of Psychology, Groningen, Netherlands.

Burman, J. T. (2018d). What is History of Psychology? Network analysis of Journal Citation Reports, 2009-2015. SageOpen, 8(1), 1-17. doi: 10.1177/215824401876

Burman, J. T. (2019). The “trust in databases” problem: Reinforcing the biases of systems used in ignorance. Paper presented at the International Society for Theoretical Psychology, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Burman, J. T., Green, C. D., & Shanker, S. (2015). On the meanings of self-regulation: Digital humanities in service of conceptual clarity. Child Development, 86(5), 1507-1521. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12395

Flis, I., & van Eck, N. J. (2018). Framing psychology as a discipline (1950–1999): A large-scale term co-occurrence analysis of scientific literature in psychology. History of Psychology, 21(4), 334-362. doi: 10.1037/hop0000067

Green, C. D. (2000). Is AI the right method for cognitive science? Psycoloquy, 11(061).

Green, C. D. (2016). A digital future for the History of Psychology? History of Psychology, 19(3), 209-219. doi: 10.1037/hop0000012

Green, C. D. (2018). Digital history of psychology takes flight. History of Psychology, 21(4), 374-379. doi: 10.1037/hop0000093

Green, C. D., Abbas, S., Belliveau, A., Beribisky, N., Davidson, I. J., DiGiovanni, J., . . . Wainewright, L. M. (2018). Statcheck in Canada: What proportion of CPA journal articles contain errors in the reporting of p-values? Canadian Psychology, 59(3), 203-210. doi: 10.1037/cap0000139

Green, C. D., Feinerer, I., & Burman, J. T. (2013). Beyond the new schools of psychology 1: Digital analysis of Psychological Review, 1894-1903. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 49(2), 167-189. doi: 10.1002/jhbs.21592

Green, C. D., Feinerer, I., & Burman, J. T. (2014). Beyond the schools of psychology 2: Digital analysis of Psychological Review, 1904-1923. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 50(3), 249-279. doi: 10.1002/jhbs.21665

Green, C. D., Feinerer, I., & Burman, J. T. (2015a). Searching for the structure of early American psychology: Networking Psychological Review, 1894-1908. History of Psychology, 18(1), 15-31. doi: 10.1037/a0038406

Green, C. D., Feinerer, I., & Burman, J. T. (2015b). Searching for the structure of early American psychology: Networking Psychological Review, 1909-1923. History of Psychology, 18(2), 196-204. doi: 10.1037/a0039013

Moretti, F. (2013). Distant reading. Verso/New Left Books. (Original work published 1994-2009.)

Nuijten, M. B., Hartgerink, C. H. J., van Assen, M. A. L. M., Epskamp, S., & Wicherts , J. M. (2016). The prevalence of statistical reporting errors in psychology (1985–2013). Behavior Research Methods, 48, 1205-1226. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0664-2

O’Brien, C. (2020, 17 Feb). EU’s new AI rules will focus on ethics and transparency. The Machine. Retrieved from https://venturebeat.com/2020/02/17/eus-new-ai-rules-will-focus-on-ethics-and-transparency/

Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in numbers: The pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton University Press.