A learning adventure in Ethiopia

by Nina Hansen, Marloes Huis, and Josefine Geiger

Picture yourself in a culture completely different from your own. Wherever you look you see colourful clothes; tiny shops selling exotic fruits; donkeys, chickens and cows blocking the crowded streets; and hundreds of minibus drivers calling out their destination. This might remind you of your backpacking trip last summer. However, we had work to do. Last spring we went to Ethiopia to conduct field research.

Nina was in charge of evaluating the impact of three different development aid interventions in Ethiopia in the field of education (mother tongue education, non-formal education, teacher training). Longitudinal field experiments were conducted to assess the impact of these interventions. This means that, two years ago, 1,500 children who had just started school were interviewed a first time. Now, two years later, we went back to interview the children a second time and to see whether the interventions had had positive psychological, social, and educational effects. We, the students, had the chance to join Nina and gain experience in conducting field research.

“We were all taught how research should be conducted in a Dutch context and which steps and factors should be taken into account, but now we needed to adjust these guidelines to the cultural context in Ethiopia.”

We soon learned that preparing research at the university, traveling to the field, and conducting the studies in a very different culture can be quite an adventure. We were all taught how research should be conducted in a Dutch context and which steps and factors should be taken into account, but now we needed to adjust these guidelines to the cultural context in Ethiopia. Not only did we encounter different habits and beliefs, but also quite different working conditions and new challenges. Before we could interview the children many other steps had to be taken. We first reviewed the literature in search of relevant measures to assess how well the children were doing. Next, we discussed our planned measures with experts in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to make sure the items suited the context, measured what we aimed to measure, and were intelligible for the children. We encountered several difficulties at this stage because of the cultural differences. For example, to measure English skills we suggested asking the children in English to point to their shoes. However, as stressed by the cultural experts, many Ethiopian children in our sample did not have shoes. We chose to include a shirt instead. After all our questions had been thoroughly discussed by the research team the questionnaires were translated to the local language by several members of the research team.

Once the questionnaires were finalized it was time to train the people who would interview the children. The interviewers were members of the community where the interviews would take place and were thus able to give further feedback on the clarity of the questions. In valuable discussions we learned more about the diversity of cultures in Ethiopia and the differences and similarities between them. Furthermore, we again understood the importance of flexibility when conducting field research as we learned that some questions were better suited for certain communities than for others. For example, the interviewers explained that children in one of our research areas would not recognize a knife as a dangerous object (we designed this item to assess environmental knowledge) because they learn to use it at a very young age, to help herd the cattle. This again taught us that even if we don’t understand all aspects of a culture, we need to take into account its uniqueness when planning and carrying out research.

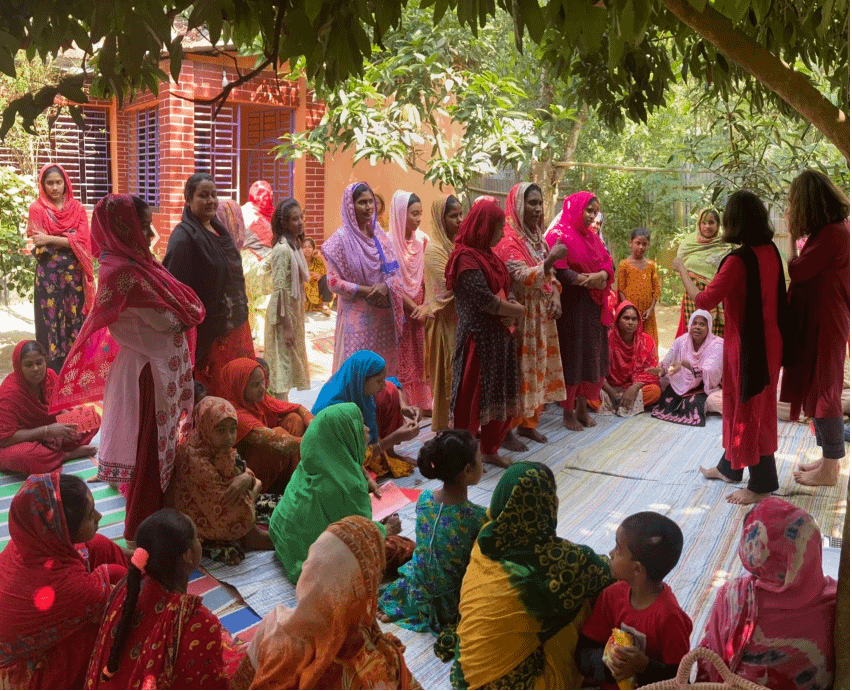

After the training we headed to an elementary school two hours from Addis Ababa. Here we carefully pre-tested our measures, in collaboration with the Ethiopian team of 2 consultants and 6 interviewers (see picture on top of page). Remember, we were conducting this research in Ethiopia so we did not have a lab with computers (see picture below). Instead, the children were called from their classroom for one-to-one interviews. They were seated somewhere in the shade or an empty room; the interviewers read the questions out loud and ci

Overall, conducting field research in Ethiopia was a great learning opportunity and a unique adventure. All four of us learned a lot about real cultural psychology outside the class-room.

References

Hansen, N., Koudenburg, N., Hiersemann, R., Tellegen, P., Kocsev, M., & Postmes, T. (2012). Laptop usage affects abstract reasoning of children in the developing world. Computers & Education, 59, 989–1000. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.013

Hansen, N., Postmes, T., Tovote, K. A., & Bos, A. (2014). How modernization instigates social change laptop usage as a driver of cultural value change and gender equality in a developing country. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0022022114537554

Hansen, N., & Postmes, T. (2013). Broadening the scope of societal change research: Psychological and political impacts of development aid. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 273–292. doi:10.5964/jspp.v1i1.15

Hansen, N., Postmes, T., van der Vinne, N., & van Thiel, W. (2012). Information and communication technology and cultural change. How ICT usage changes self-construal and values. Social Psychology, 43, 222–231. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a00012

Note: Photos by Nina Hansen