How to cure an overdose of individualism in psychology: A relational perspective on what moves and motivates us

The Dutch artist Paul van Vliet once wrote a simple yet beautiful song called “Overleven”. In the song, he observes that to survive in an individualistic world, you have to lead a selfish life in which you try to get ahead at the expense of others. Yet, at the end of the song, he concludes that although this may aid your survival, it’s not a life worth living.

In psychology, there is a similar overdose of individualism that is not worth maintaining. A peek through a random psychology textbook will offer a fragmentation bomb of individualistic theories, studies, scholars, and samples. Indeed, most psychological research takes place in individualistic cultures and thus the people who design and conduct the research, and those who are studied, are likely to view the world through an individualistic lens.

This is a problem at many levels for many reasons, including, but certainly not limited to, the core business of psychologists: Interpreting human behavior in everyday events.

“Psychological scholars are likely to view the world through an individualistic lens”

Here’s a little story. When my daughter was one year old, she once saw me eating a cookie. Now, as far as one-year-olds go, my partner and I agree that cookies are a no-go, and thus, when I saw my one-year-old looking at the cookie, eyes widening and expectations rising, as a good and consistent parent I simply told her: “No”.

The effect was more dramatic than I expected: She started crying and screaming as if she was in physical pain. In response, I soft-heartedly decided to be a somewhat less good and consistent parent — and offered her the cookie. I gave her what she wanted. But then, what did she do?

She did not take it. She did not take the cookie.

Instead, she came to me and hugged me for a long while until things were all right again.

This little story tells us two things. First, the cookie was never at stake in this situation. It hardly ever is. Nevertheless, in individualistic cultures people believe that what most people care about is the cookie. This focus on individuals and outcomes and self-interest is visible in psychology as well, on many levels. Life, it seems, is all about the cookie. But is it?

The second thing the story tells us is that people often prioritize relationships over the cookie. For my daughter and myself, it was our relationship that was jeopardized by my “no”. Both of us were doing what most of the people do most of the time: Regulating our relationships. We make sure we belong, we make sure you and I are OK. We seek the heaven (or hell, as Sartre suggested) that is the other. We seek the comfort, or prison, of embeddedness.

In my new book, coming out at Cambridge University Press, I offer a relational perspective on what moves and motivates us, as a cure for the overdose of individualism in psychology. Its starting point is that we need to understand individuals as embedded in networks of social relationships, which are embedded in different cultures that define and prioritize with whom and how to relate. Social relationships are thus not something external to the isolated individual, but reflect our very essence. There is no self without the other.

“We seek the comfort, or prison, of embeddedness.”

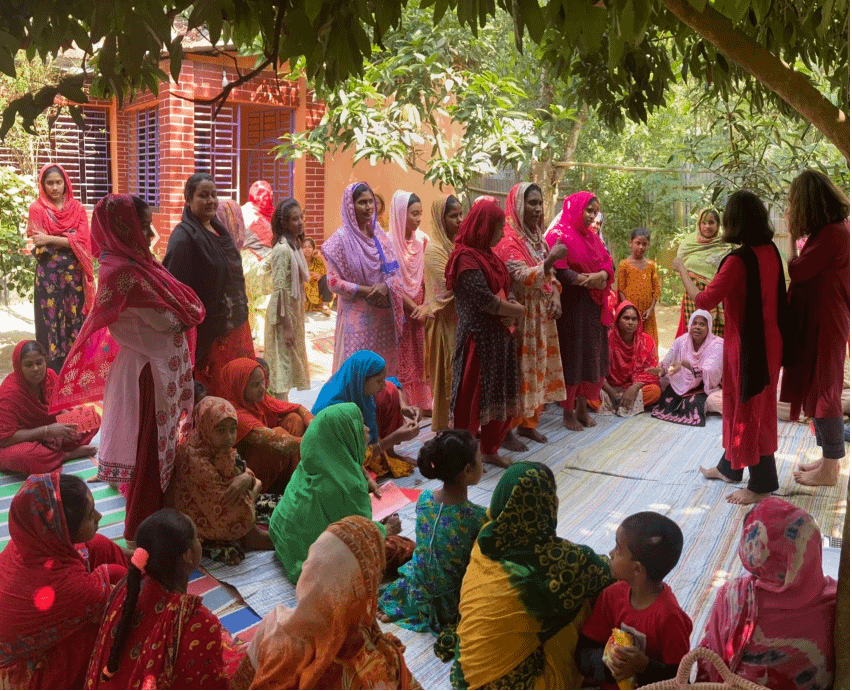

This relational perspective is nothing new and nothing crazy. From birth onwards, we relate and keep relating. Relationships, across the board, promote mental and physical health, fulfilling the fundamental need to belong, and thus people fear and abhor social exclusion and loneliness. Moreover, people often talk with others about others, and think persistently about others, even if they claim to be individualists. Ken Gergen (2009) has called this our ‘relational being’, while James Coan has referred to this as our ‘social baseline’ (Beckes & Coan, 2011). Indeed, our default is not our self, but our relationships.

From this relational perspective, it becomes clear that an overdose of individualism — a life without relational essence — reflects a life not worth living. It is difficult to understand what moves and motivates people without taking into account how they regulate which relationships, as this reduces us to our non-essentials. Moreover, I show in my book that, when we shift from an individualistic to a relational perspective, six major and relatively isolated theories in psychology (i.e., attachment, proto-self, relational models, self-construal, self-efficacy, and coping theories) suddenly become linked together. Indeed, psychological theories and studies will become much less fragmented in a relational universe that provides a framework to ‘connect the dots’. In many ways and on many levels, my new book is therefore a call for moving toward such a relational universe. It is a call for a change in how we think about psychology and about people.

“From this relational perspective, it becomes clear that an overdose of individualism — a life without relational essence — reflects a life not worth living”

A Dutch writer (Connie Palmen) once said that thinking has to involve, at some point, changing your mind. Perhaps it’s time to start changing our minds. If that sounds intriguing, go read the book.

Martijn van Zomeren’s book From self to social relationships: An essentially relational perspective on human motivation will be published soon by Cambridge University Press.

Note: Image 3D social networking from Stockmonkeys.com.

References

Beckes, L., & Coan, J. A. (2011). Social baseline theory: The role of social proximity in emotion and economy of action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(12), 976-988.

Gergen, K. J. (2009). Relational being. New York: Oxford University Press.

Van Zomeren, M. (2016). From self to social relationships: An essentially relational perspective on human motivation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.