Are Exams Killing Learning?

A few weeks ago, our University hosted Professor Eric Mazur from Harvard University, who toured the Netherlands and other countries to talk about his ideas on education and, more specifically, the way learning is assessed in higher education (and why it’s broken). I was lucky to have the chance to watch his talk and thought it an eloquent, coherent, and impassioned call for alternative methods to teaching and assessment at Universities; radical in many ways and yet familiar in others.

You can now watch the talk online and decide for yourself whether his ideas should and can be implemented (and let us know in the comments section!). For our part, we asked a student, a teacher and an administrator from our department to share their own thoughts on Mazur’s talk, so read on.

– Tassos Sarampalis

If Only Life Offered Us Multiple-Choice Answers…

by Airi Yamada, Bachelor Student

As a student in the Psychology faculty, my “success” in the program, so to say, depends largely on how well I am able to answer multiple-choice questions. Or, rather, how well I am able to recognize the correct piece of information. In fact, I still find myself quite intimidated when confronted with an open question after two and a half years of deciding between a, b, c, or d. They’re actually asking for my opinion! This makes myself, and others included, question my own ability to survive in a real-world context where choices are not so readily offered upfront.

However, it is important to note that we have a history of not being tested according to the real world. Ever since elementary school, unit tests and pop quizzes have always been a part of my learning experience. As students, as learners, we were constantly rewarded with marks of “100%”, “A+” or “10/10” for recalling correct information and showing that we know something. This notion of “knowing” ranged anywhere from verbatim definitions of specific terms to a complete memorization of the periodic table of elements (I remember fearing questions starting with: Explain in your own words…”). Take a few students who are able to accomplish this, ask them to apply their knowledge to a situation, and suddenly you’ll find their understanding to be near 0%. We have, from a very young age, learned to trust and accept information from what we are told to read. Neither I nor my elementary school classmates ever initiated a discussion on why or why not an answer is correct; if an answer was marked wrong, then it was wrong.

It is certainly not only the higher education system that needs to change; it is the education system as a whole and how learning is approached. Even after all these years, the “read the textbook and you’ll pass” idea never quite diminished among university students. This is partly due to the fact that the study habits developed over the course of so many years involve, unsurprisingly, reading the assigned textbooks. Combined with the fact-based questions asked in the exam (some taken quite directly from the reading material), it is hardly surprising that students rely on provided knowledge rather than external sources. While it is true that critical thinking has been taught extensively to us, we have not been given the opportunity to be critical when taking our exams. It is not so much the grading aspect that makes assessments artificial, but the process of carrying it out. Why am I only allowed to choose one answer when I can argue that two of them could be equally plausible? Giving students greater leeway in explaining themselves could lead to the generation of “creativity” that Mazur mentioned. Instead of testing students’ knowledge solely on assigned readings, an effective alternative might be to test their ability to construct arguments based on information gained from a variety of sources.

Let’s replace students with robots! An absurd proposal to deal with absurd assessment

by Stephan Schleim, Associate Professor

Eric Mazur criticized our ways of assessment, particularly our exams: They were testing inauthentic problem-solving with a focus on the result, not the way how to get there. Assessment primarily fulfilled the need for ranking and classifying, without even being very good at that. In his conclusion, Mazur claimed that our tests should mimic real life and that professors should primarily provide feedback, not calculate rankings.

During my own time as a student, research associate, and now professor, I witnessed the transition from free universities to the present kind of knowledge-production factories that are managed by controlling their output figures. I am more skeptical than ever that the reforms of the past fifteen years improved higher education. They changed the way we do our academic work as well as the education provided to the students, particularly examinations.

A man-made problem of higher education

Why needed there to be reforms, first of all? The major problem of universities in many European countries was the increasing number of students in spite of a corresponding increase in means for education. The OECD still calls for higher rates of academics. This problem thus is made – or at least negligently contributed to – by politicians. Besides that, those currently in leading positions were frequently educated at free universities – and economies were strong and stable in the 1980s and 1990s. Therefore, the burden of proof rested on those passing the reforms to first demonstrate flaws in the old system and then provide evidence that their reforms are the solution.

A lack of confidence

In contrast to that, politicians started to doubt that we cannot be confident of our education system’s quality without assessment, in spite of all the real life evidence for that (including their own education and general social welfare). I would not be surprised if those who later benefitted from the assessment epidemics convinced politicians and society at large that without assessing quality in their way, there can be no confidence in it. What happened then is history: Increased formalization, increased standardization, increased testing, increased bureaucracy –– and, as far as I can see it, increased frustration among professors and students.

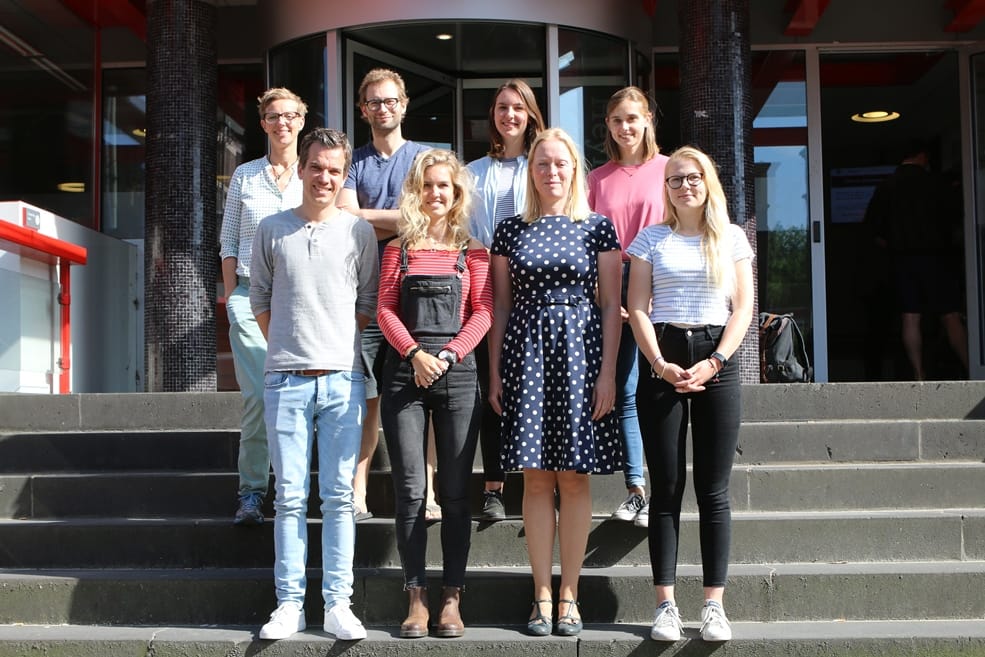

Image 1: A common standardized ritual at universities nowadays: Forms are distributed right before the multiple choice exam of my Theory of Science course.

Let robots do the work!

My proposal is to build robots to produce the kind of information pleasing those in favor of assessment, those who require us to do it. In the meantime, before such robots are available, assessments that provide no valid information should be done away with. That particularly counts for those that are required and designed by people who have no idea of the primary process that is being assessed. Both ways, students and professors can then focus on that what universities are there for: providing higher education, academische vorming in Dutch and Bildung in German.

Group work can be much more realistic

In my daily practice I let students vote themselves whether they want grades or not, where that is possible, such as at the Honour’s College. So far, they always voted against (though there is a small minority in favor of grades). Where it is not possible, I try to add group work as part of the examination, in line with Mazur’s critique that common exams do not reflect real world-problems. For example, in the fifth session of my course Philosophy of Psychology, students must apply knowledge from the previous lectures as members of groups of three or four. That is, they must analyze an experimental study and compare that to common science communication in order to answer a couple of questions that count for the final grade.

Image 2: An alternative to the previous situation: Usually, students are not allowed to collaborate. That counts as cheating. In this case, students had to discuss and solve applied problems as a group. (Image blurred for reasons of privacy.)

Exams as a way of learning

As communication is becoming ever more pervasive in our life, this reflects a real problem – and a real problem-solving strategy, as they work together and are allowed to use all kinds of sources. Beyond that, this procedure is part of the real work of a philosopher of psychology. From my experience, this is a great tool for learning and assessment, although it is not without limitations: Think about the free-rider problem that can occur in group work, people who get points although (mostly) their teammates did the work. In an ideal world, we could probably get rid of grades at all, as Eric Mazur suggested in his talk, and trust both students’ and professors’ intrinsic motivation. However, Mazur could not yet convince his own dean at Harvard and a discussion of the philosophy of grading would require more than a few extra blogposts, I am afraid.

Lessons Learned

by Sabine Otten, Education Director

Honestly, I was skeptical when entering the lecture hall to listen to Eric Mazur’s talk “Assessment, the silent killer of learning”. Just a hype and a fancy, provocative title? – A bit later, I was sure it was a good decision to attend. Not necessarily because all I heard might be easily implemented in our own teaching, but because Mazur alerted me to topics that are worthwhile to address and/or reconsider. And because the lecture in itself was a convincing example that it is possible to keep a big audience focused and engaged for more than 90 minutes!

But enough meta-communication: What exactly did I learn about teaching and assessment? Well, first of all, there was the valuable reminder that a core function of assessment may be feedback rather than mere grading and ranking. And Eric Mazur reminded his audience about the necessity to formulate proper learning goals and to unambiguously align the assessment with those goals. I am not sure whether members of our test committee (‘toetscommissie’) attended; if so, they certainly (at least silently) applauded at this point. And while it makes of course a lot of sense to strive for such clear learning goals and their proper assessment, this does not come automatically and needs training. Which is exactly why I am planning to offer regular classes to teaching staff on how to formulate exam questions (both open-ended and multiple choice) that are in accordance with the intended learning goals.

The inappropriate loneliness of taking an exam – this was the second lesson. Indeed, carefully isolating students from their fellows, but also from all useful media (e.g., books, the internet), does not give a lot of ecological validity to the exam-situation. Such conditions provide excellent grades for excellent remembering, but tell little about students’ ability to retrieve and use knowledge in order to deal with novel problems. Hence, why not give people access to the knowledge they can look up outside the exam halls and assess how they use this knowledge in new contexts? Again, this is certainly something I would like myself, and all teaching staff in Psychology, to learn more about.

Relatedly, Mazur presented examples of how team work can become an integral part of assessment. In his classes, only 50% of the grade is determined by individual performance, and the other 50% by performance on team level. Team-level performance is made especially engaging by creative grading forms and a sophisticated system of (changing) team composition to avoid systematic differences in within-team social and intellectual competence. I must say, I was impressed by the videotaped examples showing that exams in small teams may provide both fun and continuous learning.

Yet, at this point, I also heard some protest from my pragmatic self: Are we allowed to do such form of grading? May students sue us because they think they ended up in a ‘wrong team’? Is such procedure in line with the Bologna-rules that our ministers of Education agreed upon? And what is doable and manageable with a limited number of lecture rooms and large groups of students rather than a small elite cohort from Harvard University? – I am not sure, but will check. Yet, Mazur’s lecture inspired me to consider such options and try to do whatever we can within our legal and contextual limits in order to make our assessment an integral part of our students’ learning.