Aletta Jacobs – A Dutch Feminist

On April 20 1871, a young student entered the University of Groningen; a student who was very much unlike the fellow students. It was Aletta Henrietta Jacobs (1854-1929), the woman who would later become the first female university graduate in the Netherlands, the first female doctor, and a passionate fighter for liberty and equality. Unlike men in her time, she could not just register for a study program; women were not given the same opportunities in the education system and supposed to practice skills qualifying them as good housewives instead.

Self-confident as Jacobs was, she had asked for an exception; and for this she had approached nobody less than the Prime Minister of the Netherlands himself, the liberal politician and law professor Johan Rudolph Thorbecke (1798-1872). He had previously played an important role in revising the Dutch constitution to shift power from the king and nobility to the people. Would he take her request seriously, or rather suggest that she learned something “more appropriate” for young women?

Permission Granted

After some correspondence, naturally involving Jacobs’s parents, the Prime Minister eventually granted her permission to enroll in the university – but only for a probation period of one year! These were times where many people, including many women, did not only think that women should not attend university. No, they even thought that they simply could not, because they lacked the necessary skills.

While the Prime Minister’s decision paved the formal path for Jacobs’s enrollment, many obstacles remained: People just were not used to the idea of women studying at a university, social resistance and gut feeling could not be changed by a single ministerial letter, and even the newspapers throughout the entire country made fun of the female student in Groningen! Obviously this also caused tensions for her family, but there she also met support.

Undistracted by the extracurricular pleasures enjoyed by many of her fellow students, like the infamous drinking bouts of the oldest student association of the Netherlands Vindicat, which she was not allowed to join as a woman, and with both academic passion and an extraordinary aim guiding her, she was succeeding at the exams. Yet when the end of her probation period approached, she was informed that Prime Minister Thorbecke was terminally ill. It must have been impossible for Jacobs to predict whether his successor would extend her permission to study – or send her home to do “women’s work”. Thus she hurried to show Thorbecke evidence of her successes. The Prime Minister granted her the permanent permission only four days before his death, one of his last official acts.

Medicine for Women

Aletta Jacobs passed the medical doctor’s qualification in 1878 and defended her doctoral dissertation on March 8 1897 – by chance the day that would later be recognized as International Women’s Day. Her dissertation topic was the localization of physiological and pathological features in the cortical brain, an idea that would experience a renaissance in the 1970-2000s thanks to the emergence of brain imaging techniques such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Notably, while the idea of localized functional specialization of the brain (as opposed to the idea of a holistic and equipotent network) was quite popular in many countries during Aletta Jacobs’ lifetime, there were few people investigating it in the Netherlands – and Aletta Jacobs was one of them (Eling, 2008).

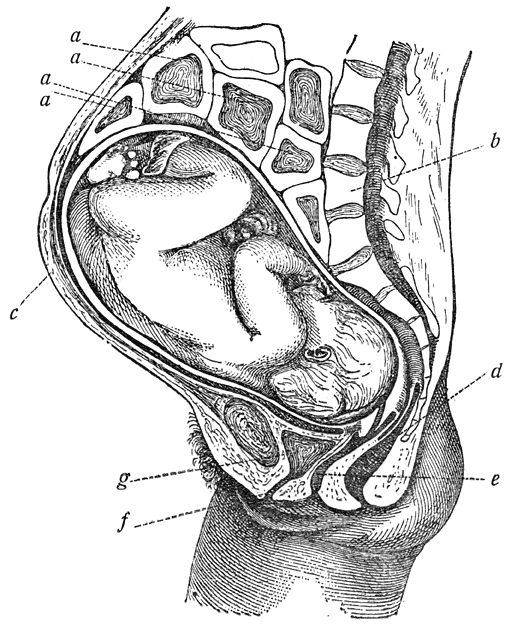

Her medical practice and political activities were shaped by her unique experiences of being one of the first women in Dutch society to live an independent life. She published a popular medical book in 1899 in which she explained basic functions of the body (Jacobs, 1899a). In the first part she covered those organs she considered to work equally in men and women; the second part extensively addressed the sexual organs as well as the stages of pregnancy. This might have been the first time her contemporary female readership was able to obtain medical knowledge on what they had so far only known from hearsay and personal experience.

Illustration out of Aletta Jacobs’s book on the female body (1899a), showing the pelvis during the last month of pregnancy (provided by Schroeder).

A Fighter for Liberty and Equality

Besides her medical work, she was also politically active. In the year that she published her popular account on the female body, she also published an article on the aims of the women’s movement (1899b) and female concerns (1899c). Her three major claims where the economic and legal independence of women, the legal regulation of prostitution, and the deliberate restriction of the number of children. While many of her contemporaries thought that her ideas posed a threat to social order, in particular marriage, Jacobs argued that equality would be beneficial for everyone, even the husbands:

But experience has shown that the independence of the woman does not only not undermine marriage, but on the contrary contribute to putting it on a more moral foundation. A woman who has learned to float with her own wings, to maintain her own livelihood, will only agree to a marriage when genuine affection and congeniality motivate her. Then the union can be pure and uplifting, only then can there be a moral relation and genuine happiness. (Jacobs, 1899b, p. 509; author’s translation)

In the same text, she responds to claims by some of her contemporaries such as Cornelis Winkler (1855-1941), professor for psychiatry and neurology at the University of Utrecht, who argued that women are generally unfit for higher education. While Aletta Jacobs’s primary aims were women’s rights, her underlying political philosophy emphasized equal rights and liberties of all human beings. Not only the British philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was an inspiring source for her, but also someone who is still known worldwide, and shaping statistics lectures, today: the British mathematician and political philosopher Karl Pearson (1857-1936). Pearson had not only conducted research on probability, but also wondered how a just and equal society could be established, for example, in his Ethic of Freethought, quoted by Jacobs as a support for her aims (Pearson, 1888/1901).

Aletta H. Jacobs today

Aletta Jacobs and her ideas are still surrounding us today. Students in Groningen have likely taken exams in the Aletta Jacobs Hall at the Zernike Complex. They and other people in Groningen have passed her sculpture in front of the university’s Harmony Building many times. There is a permanent exhibition in the University Museum displaying Aletta Jacobs’ consulting room and original tools she used for her medical practice. And now that the University of Groningen celebrates its 400th anniversary, there is even an Aletta Jacobs musical played at historical sites and in the City Theater, with performances in March and June.

Aletta Jacobs can still inspire us today. She does this by posing an example that it can be worthwhile to fight for an idealistic aim, even if it may take a whole lifetime or longer for success. In the musical, Jacobs’s father provided her with consoling advice when she faced the enormous social resistance:

First they will laugh at you; then they will get angry at you; then they will be silent for a very long time; and then, eventually, they will say that it had originally been their own idea anyway. (author’s translation)

References and Sources

For biographical information, see the Aletta H. Jacobs website

Eling, P. (2008). Cerebral Localization in the Netherlands in the Nineteenth Century: Emphasizing the Work of Aletta Jacobs (use the university library to get full access). Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 17, 175-194.

Jacobs, A. (1899a). De Vrouw: Haar bouw en haar inwendige organen. Deventer: Kluwer.

Jacobs, A. (1899b). Het doel der vrouwenbeweging. De Gids, 63, 503-522.

Jacobs, A. (1899c). Vrouwenbelangen. Amsterdam: L. J. Veen.

Pearson, K. (1888/1901). The Ethics of Freethought and Other Addresses and Essays. London: A. & C. Black.

Copyright information

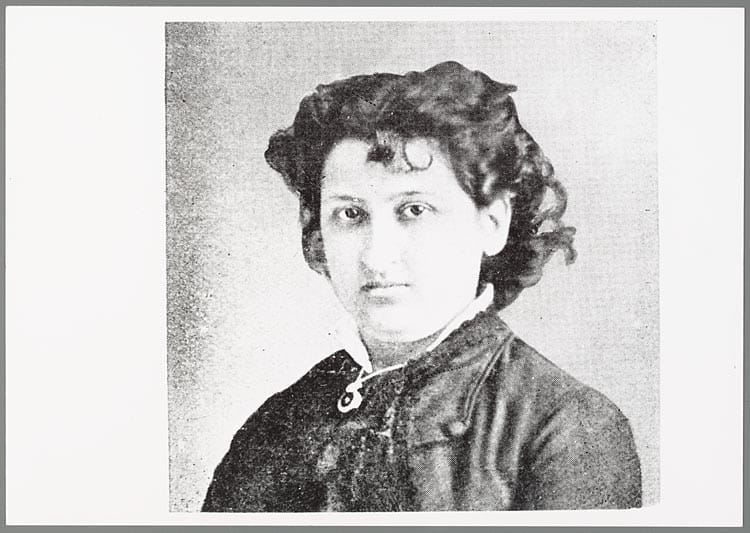

The photograph of Aletta Jacobs is taken in 1878 and provided by Het Geheugen van Nederland; because of its age it is public domain.

Version history

- John Stuart Mill was called an American philosopher in the original article, although he was British. This has been rectified on March 25 2014.