The Art of Science: An interview with Mila Moxom

Valeria Cernei, member of the Mindwise team and soon-to-be-graduate from the Groningen Psychology programme, has been moonlighting as writer for the BCN Newsletter for the past few months. She recently interviewed Mila Moxom about the way in which her bachelor’s degree in psychology from the RUG influences her artistic vision, an art project that blends the boundaries between art and science, and the ethical responsibility that comes with the scientific progress and technological advances.

Valeria Cernei: The topic of your art project is science and technology. How did the project start?

Mila Moxom: After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Groningen last year, I started attending the LUCA school of Arts in Brussels, Belgium to study photography. As an assignment, we had to come up with a project which centres on the topic of science and technology. My teacher suggested I take on a critical or rather negative standpoint towards science and technology. For me this was not possible. There are many ways in which progress in science and technology benefits society, but, of course, nothing has only positive sides. I think the two are inseparable. Thus, taking a stance only against the negative side would mean I am not willing to see the positive aspects to it.

VC: What may be some of the reasons the topic of science and technology tends to come with a negative connotation?

MM: I think one of the issues at hand is that many people don’t understand technology and science. What I realized is that academics tend to interact with academics, and non-academics with non-academics. To my own surprise, coming from a research university into photography class, I was confronted with other students’ projects about science and technology, which mainly focused on photographing nature and conducting museum or archive visits. What I am trying to say here is that there is a big difference between people with different backgrounds in terms of their interest in science. I think this can get rather counter-productive. With my project, I wanted to bring my former research surroundings into photography, and share it with people that will attend the Breda Photo Festival, where the project will be presented.

VC: Which of your experiences as a psychology undergraduate student were most valuable in shaping your approach to this art project?

MM: There are several pieces to this puzzle. The first one is about my interest in the facial expression of emotions, which started during my second year of my bachelor’s degree. At that time, I was a research assistant, running a study investigating the recognition of facial expressions in people suffering from schizophrenia. It has been found that those suffering from schizophrenia have deficits in detecting facial expressions of emotion comapred to healthy individuals, which we further elaborated upon in our study. I have two books about facial expression of emotion that I used to read when I was bored; everything starting from Darwin’s theory about universal facial expressions, to research done by Paul Ekman and W.V. Friesen. I was fascinated by it, and secretly always dreamed of recapturing those 6 basic, “outdated looking” emotions.

Another important piece of this puzzle is being introduced to the possibilities of pupillometry. At a time when I urgently needed money, my friend offered me the opportunity to participate in his eye-tracking studies. At that time, he was a research assistant working with Sebastiaan Mathot, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Experimental Psychology. His main research is about pupillometry, the measurement and study of pupil size and reactivity. The pupils become smaller or bigger depending on the amount of light that falls on the eyes. Recent research in this field suggests that the pupil light response occurs even when people shift their attention to a bright or dark object without moving their eyes. Based on this premise, Sebastiaan and his research team are working on developing human-computer interfaces that decode what’s in the focus of people’s covert attention. Such eye-tracking devices can be used to communicate with people with locked-in syndrome by teaching them to select letters or words using covert attention. Sebastiaan Mathot’s program used flickering letters, which one could use to write a whole word just by covertly attending to each one of those letters!

I do think there will be great developments in this area it in the next years, from which we could benefit in various ways. For example, pupillometry could also be used in the clinical setting as a diagnostic tool, or even in order to study people’s behaviour when looking at art. But I think there is more than enthusiasm to be felt, because, on the other hand, there are many big companies such as Apple and Google which invest in eye-tracking devices and use them for their own (not as beneficial) purposes. There is already a lot of eye-tracking involved when it comes to gaming or phones. I think there’s a thin line between good and the bad aspects to it, especially when we think about the future. For instance, there is no one who knows me better than my phone knows me. It knows more about me than my parents or my best friend. And I wouldn’t want to imagine what more it will know about me, my psychology and physiology in the future…

VC: At this point, I sense an overarching concern of yours regarding the ethical implications and the responsibility, both at an individual but also at a societal level, that comes with knowledge and technological advances. How do these pieces come together in your project?

MM: I knew I wouldn’t be able to do research on the facial expression of emotions or pupillometry, but, nevertheless, the idea came about, and I wanted to create a project that combines the two. I wanted to have a program similar to that used by Sebaastian Mathot, with the sole difference of using photos of emotional facial expressions instead of letters in order to construct collages composed of various facial emotions. But let me start from the beginning.

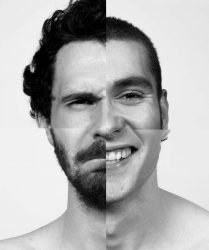

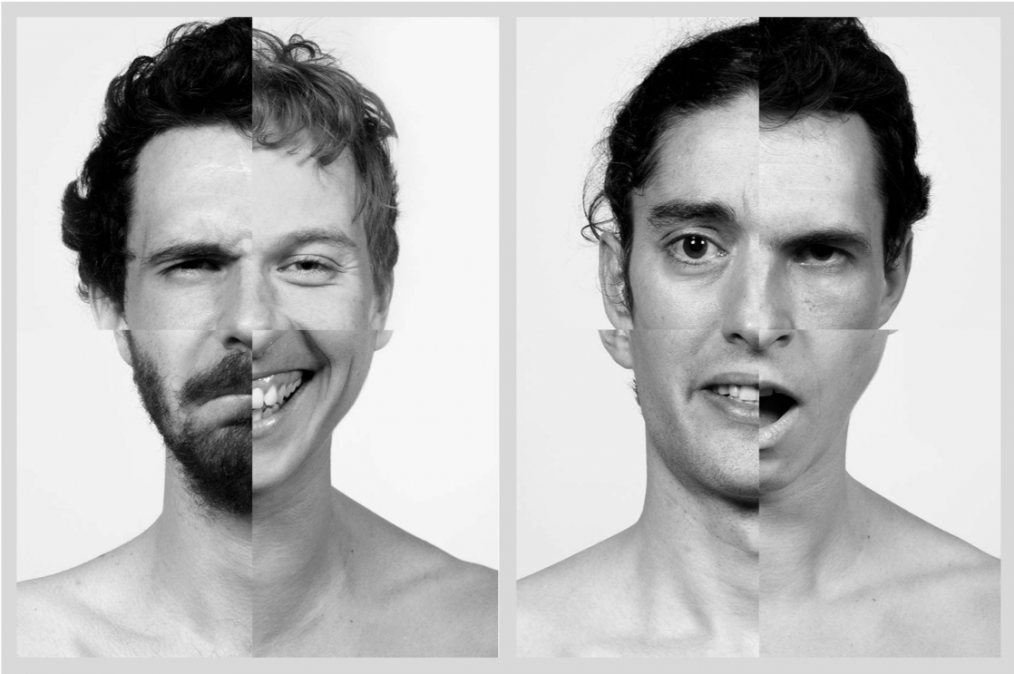

First, I took photos of people’s facial expressions. I used Ekman & Friesen’s six basic emotional expressions as a basis and recorded the different stages of showing one emotional expression. After I took all the pictures, I cut the faces into 4 pieces, so that you only see 1/4 of the facial emotional expression.

Yavor Ivanov, a student from the BCN program has built the program that I have mentioned.

The program is a human-computer interface, which uses the same technique as already discussed (Mathot, Melmi, van der Linden, & van der Stigchel, 2016). It decodes the locus of covert attention using pupillometry. A person looks at a fixation point that has two photos on its side, and shifts and sustains his/her attention to one of the photos. The photos will flicker brighter and darker, and the currently attended object’s light will trigger a relatively weak pupil light response. The interface will detect the pupil’s fluctuating size over time, gather evidence, and try to guess which image one is attending to in their mind’s eye. After a few pictures of the puzzle are shown, and a few choices are made by the software, the viewer is presented with a new, distorted face staring back at them. Almost like an alien.

VC: What message are you trying to communicate to the audience through this innovative medium?

MM: Nowadays, I get the feeling we more and more lose control over technology and its impact on our lives. Scandals, such as that regarding Facebook data ending up at Cambridge Analytica without prior agreement, make us aware of how little we can influence what we give away in terms of personal information shared online. I guess most of us had this moment, where you thought about something, and then saw an advertisement on your screen with the exact thing you just had in mind. Even though some regard it as a conspiracy theory, it is just progressive technology, apps tracking our conversations, our microphones, our entire phone contents, including our contacts. This information is retrieved without our explicit approval, and used to personalize advertisements, their content and timing. In the future, who knows; they may use it for more than just marketing…

Our program itself cannot help humanity, but human-computer interfaces that have an ethical idea behind them will do that. Our program will hopefully help by making people more aware of what’s currently possible with technology. But it can also have darker applications.

All I can say is that we become more and more alienated without mostly realizing or knowing much about why and how. The only thing I know is it will have both good and bad effects. Hence, the range of emotional expressions. One can be happy or sad, surprised, angry, fearful, or disgusted about science and technology, its fast development, and about how we willingly adapt to it. I think the complexity of the whole spectrum of emotions defines the relationship humans have with science and technology. However, the most important thing is how we use technology and how we will deal with it in the future. It depends on ourselves. In the end, I wanted to hold a mirror up to us, humans.

As a final thought, we could do worse than revisit what Schopenhauer had to say on the relationship between art and science. “While science, following the unresting and inconstant stream of the fourfold forms of reason and consequent, with each end attained, sees further, and can never reach a final goal nor attain full satisfaction…; art, on the contrary, is everywhere at its goal. For it plucks the object of its contemplation out of the stream of the world’s course, and has it isolated before it.” It is not, however, the differential means of art and science that should be allowed to separate the two; rather, their common meaning should be allowed to bring them together. Both are deeply rooted in the human need for transcending the narrow bounds of individual experience to comprehend, and, thus, to become part of a universal reality. Mila’s art project traverses the boundary between the two, only to make one realize that what seems from afar to be a limit, is but limitless opportunity. It comes as an illustration of the complementarity of art and science, and the ways in which they feed and provide context for one another.

For more pictures from Mila’s project, visit https://hummanus.tumblr.com/.

All images by Mila Moxom

References

Mathot, S., Melmi, J. B., van der Linden, L., & van der Stigchel, S. (2016). The Mind-Writing Pupil: A Human-Computer Interface Based on Decoding of Covert Sttention through Pupillometry. PloS ONE, 11(2): e0148805.