“Een wereld vol denkers”: A book by Sebastiaan Mathôt

Marie-Christine van de Glind, PhD student at UMCG, interviewed our colleague Sebastiaan Mathôt, who recently published his book Een wereld vol denkers: Op zoek naar het bewustzijn van mens, dier en plant (en misschien zelfs AI), about consciousness in humans, animals, and plants (and maybe even AI). This interview was previously published in the BCN Magazine.

Sebastiaan Mathôt is a cognitive neuroscientist and associate professor at the University of Groningen. His research focuses mainly on attention and visual perception. He is also developer of the open-source software OpenSesame, used to create experiments for psychology, neuroscience, and experimental economics, and has a specific interest in AI. He is currently involved in creating Heymans AI, an AI tool for education, which can be used to check simple open-ended questions in exams.

For readers new to your work: what core question does your book tackle?

What are the commonalities between all the various forms of thought in the world around us? Living organisms and advanced AI have behaviors that are guided by some form of thinking. I don’t mean ‘thinking’ in the sense of Rodin’s The Thinker. A plant doesn’t reflect on the meaning of its existence. But ‘thinking’ in the sense of cognitive psychology. Cognition is after all just a jargony synonym for thinking, which at its core consists of basic cognitive processes.

How do these basic cognitive processes guide thinking, and how can we recognize them in all ‘systems’ in your book, from humans to plants and AI?

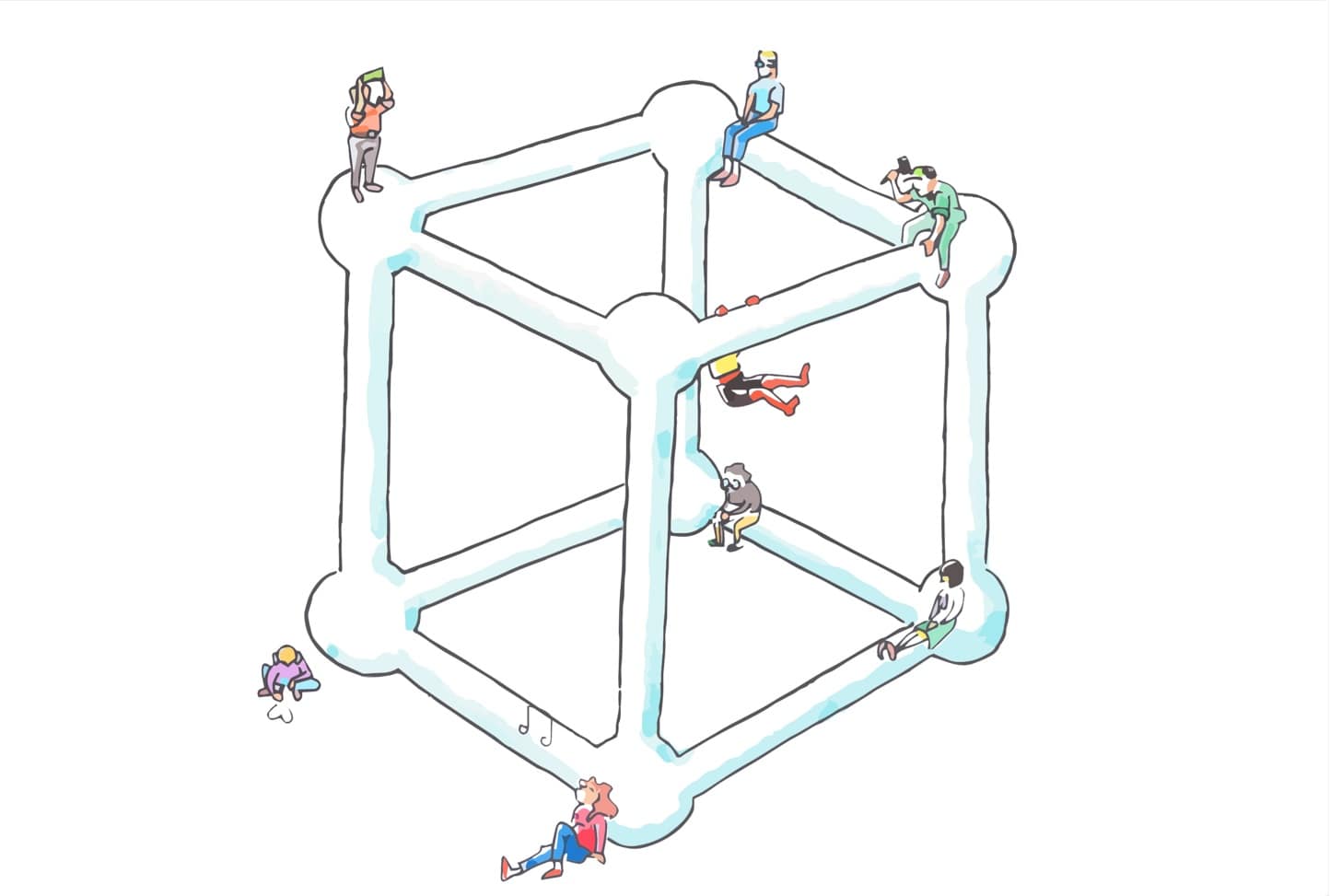

To me, basic cognitive processes, such as perception, memory, emotion, and feeling, are building blocks. More advanced forms of thought, such as those that we associate with intelligence and social behavior, result from stacking these building blocks in ever more complex ways. Some thinkers build extremely complex thought processes this way; think of crows, octopuses, and AI chatbots. Other thinkers keep things simple; think of plants and flatworms. But the building blocks are often similar.

If you look closely, there are lots of similarities in how humans, animals, plants, and AI think. But there are also differences, and these differences are just as fascinating and important.

Let’s take a look at some of these building blocks. Perception is about detecting information, either from the outside world (light, smell, sound, etc.) or your own body (limb position, etc.). Perception is also about doing something useful with that information. Animals aren’t the only beings who perceive things. When a buttercup flower tracks the sun as it moves across the sky, this heliotropic movement is also an example of perception with a corresponding action.

Memory is about using past experience to guide future behavior. Again, animals aren’t the only beings who have memory. Memory also exists in various forms in plants. And you could even say that a chatbot consists of pure memory.

If you look closely, there are lots of similarities in how humans, animals, plants, and AI think. But there are also differences, and these differences are just as fascinating and important. For example, although plants have memory, the kinds of memory that they have are very different from our own. Plant memory tends to be less flexible and more tailored towards specific purposes, such as getting ready for spring. The familiar categories of human memory (long-term memory, working memory, conditioning, etc.) don’t apply to plants. And what about AI? AI definitely has memory, but what kind? The memory of a chatbot has some similarities to human memory, but there is at least one crucial difference: a chatbot has no personal memories (what psychologists call episodic memory). Its memory is factual, disembodied. These are things that fascinate me.

What about emotions and feelings, which may seem less applicable to plants and AI?

Emotions and feelings are like signposts that point living organisms in the right direction, such as by fleeing from things that are scary or painful, and seeking out food and companionship. Emotions and feelings are in a sense the cognitive tip of the iceberg, because similar processes extend across all levels of life: from the immune system to cellular processes involved in DNA repair—living organisms are continuously working to survive. These life processes (for want of a better term) are a core aspect of what it means to be alive.

In this respect, AI is fundamentally different from living organisms. The current generation of chatbots don’t continuously work to survive. They just are. This has to do with embodiment, or lack thereof. Most current AIs are not physical entities. They’re not even clearly defined software entities. ChatGPT briefly comes into existence when you ask it a question. As soon as it has generated a response, it vanishes, only to briefly come into existence again, perhaps in a different data center, when you follow up with another question. There is nothing that you can point to and say: that’s my chat, that’s the entity I’m currently talking to. There is no body.

If you don’t have a body, you also don’t need emotions and feelings to point you in the right direction so that you don’t die. Therefore, it’s difficult to see what emotions and feelings would even mean for an AI like ChatGPT. Probably, at this point, they don’t mean anything.

In the book, I link this to consciousness: to the question of whether AI has subjective experiences; whether, as Thomas Nagel famously described consciousness, there is something it is like to be ChatGPT. Many researchers and philosophers believe that consciousness is related to emotions, feelings, and other life processes. If this view is correct—which no one knows—this would mean that current forms of AI do not have consciousness, or only a sliver of it. But it also means that this may change in the future, as AI develops and becomes more embodied.

The cool thing about plant behavior is that you can easily study it at home. All it takes is a few pots, a clever experimental design, and a lot of patience

Consider a current example: a robot vacuum that plugs itself into a power outlet when the battery runs low. This behavior is a life process, perhaps akin to hunger, because the robot does something to keep functioning. It’s an extremely simple process if you compare it to all the ways in which living organisms try to survive. But it’s a start. From there it’s easy to imagine sophisticated forms of AI with a body and something that resembles emotions and feelings to keep their body intact. Think of an AI chatbot program that exists as a file on your phone. This chatbot has a body, even if it’s just software, because there’s a file you can point to and say: that’s my chatbot. Perhaps this chatbot will do anything in its power to prevent you from getting a new phone. And perhaps there will be something it’s like to be this chatbot.

Let’s get back to plants: If you could run one decisive experiment on plants tomorrow, what would convincingly support (or rule out) plant experience beyond complex signaling?

I would focus on operant conditioning. If someone would manage to train a plant through reward and punishment to grow in a specific direction, then this—unspectacular though it may sound—would be revolutionary. It would bring plant thinking much closer to animal thinking. This is again about emotion and feeling, because training through reward and punishment is of course only possible when an organism experiences something as pleasant or unpleasant.

There have been some attempts to do this, but so far without success. (Or initial success followed by failures to replicate.) The cool thing about plant behavior is that you can easily study it at home. All it takes is a few pots, a clever experimental design, and a lot of patience.

As a researcher, you have published numerous articles, but writing a popular-science book is something different. What were your experiences writing Een wereld vol denkers?

My main motivation to write this book was that I enjoy thinking and writing about interesting stuff. I particularly enjoy writing when you have the freedom to take the story in any kind of direction you want. Academic writing doesn’t provide that freedom—and for good reason. Nobody wants to have to dig through a philosophical exposé in order to get to the meat of a scientific experiment. As a reader of a scientific article, you want information, and you want it fast. There’s a lot of skill involved in effective academic writing. But it’s formulaic.

Writing a book is more fun, because you have the freedom to choose your own form. It’s just as important to stick to the facts when writing a nonfiction book as when writing an article, but you have more freedom to choose how you want to do this. And there’s more space for context and personal reflection.

The form that I chose is a bit like a visit to a museum. I introduce the reader to interesting, beautiful, and strange beings, all with their own unique forms of thinking. In doing so, I hope to convey a sense of awe and beauty. And I try to provide context: a general narrative thread that ties all of these seemingly disparate examples together. Without pretending to present a Grand Unifying Theory of Thought. In fact, one important message of the book is that there is no such theory. Cognition is part of the natural world, and as such it’s diverse, chaotic, and not easily captured in simple definitions and theories.

Your work as a BCN researcher primarily focuses on attention, visual perception, and pupil size. How does this book relate to your academic work?

The book is not directly about my own research. I believe my research is valuable in the narrow sense that most specialized research is valuable. But the book is about bigger questions, which my own research doesn’t tackle. That’s how it should be, I think. A scientific experiment is the place to test a single small idea. That’s the daily grind of research. A book is the place where many big ideas can come together.

From a Groningen/BCN perspective: what ambitious cross-lab project would you launch to push this field forward, and why here?

I would be interested in taking a look at labs studying insect vision, such as the group of Casper van der Kooi here in Groningen. At first just as a passive observer, to get a feeling of the methods and paradigms that they use. I would then think of research questions that behavioral biologists might not ask themselves, but that come naturally from my perspective as a cognitive neuroscientist.

For example, it is well known that bumblebees (my favorite animal 🐝) can learn complex things. In real life, they seem to copy each other’s foraging style. In the lab, you can even teach them tricks, such as pulling on a string to receive a reward. I wonder to what extent their memory processes are similar to ours. Do they have something analogous to working memory as distinct from long term memory? Or does this distinction not exist in their minds? And if they have working memory, does it function similarly to ours?

What advice do you have for other researchers dreaming about writing a book?

To start, write a book only if you genuinely enjoy writing. It’s awesome to see your book in bookstores. You might get some media attention. But that’s about it. You won’t get much more in return for your efforts. So your motivation should mainly be intrinsic.

Also: start small, with short stories or blogs or anything to get your pen moving. Many researchers only write a few times a year, typically when they’re working on a scientific manuscript or grant proposal. That’s not a lot. Going from there to writing a book is a big step. So practice first! Otherwise, you’ll be rusty and you’ll likely find the process daunting and unpleasant.

Once you have an outline and ideally also a draft of at least the opening chapter, you can approach a publisher. There aren’t that many academics who write nonfiction books, and yet quite a few publishers who publish such books. This means that if you bring a solid proposal, publishers are likely to at least hear you out.

So: don’t underestimate the process, but do give it a shot if it’s something you’re really interested in doing!

Image credit: photos by Marie-Christine van de Glind, used with permission