Excavating the Heymans Cube – How early personality science can speak to the present.

Thousands of academics publish new research every day. While that is great, it also means that the research of yesterday is often quickly forgotten. That is a waste of valuable resources, because even theories from a century ago can turn out to be treasures worth excavating.

When I decided to write my PhD dissertation on the Heymans Cube, a personality theory from the early 20th century, I wanted to strengthen my personal connection with the topic by own copies of the original books (A digital scan of the originals can be found here: Part I and Part II). Through an online second-hand book platform, I found the contact information of someone who owned a copy. I immediately emailed this person, Frank, with a request to buy the books. Frank called me the next day to say that the books were somewhere in his attic, certainly, but that he might need some time to find them in the mess. He hadn’t seen them in some time, at least since his retirement. Frank’s sister had urged him to get rid of all the old things he had collected over the years, which is why he had listed many of them for sale. He would get in touch again when he had located the books. Sure enough, the next day, I received another phone call. After rigorously combing through his attic, he discovered that they were in an entirely different spot than expected: on his nightstand. Realizing which books I wanted, Frank told me that the books meant a lot to him. They had made a great impression and he had regularly reread them over the years. This emotional reaction surprised me. Clearly this man was loath to part with these books, so I offered that I could continue my quest elsewhere. He should hold on to his copies. The phone went silent, then I heard a deep sigh. No, Frank insisted, his sister was right and he should really reduce his clutter. He would send me the books right away.

A few days later, I finally held the copies in my hand. The work was divided into two pocket-sized hard cover books, much smaller than I had expected. One of the spines barely held on to the book by a thread, and both had discolored from a mossy green into a faded yellow. Nevertheless, as soon as I opened them, I understood why Frank had struggled to part with them. I was sucked in right away. After outlining the aims and methods of the book, it started with the simple observation that everyone knows what it is like to be conscious. From there, the books carefully and with striking clarity outlined increasingly complex phenomena. How sensations form into perceptions, how we remember and forget, feel and think, act on motivations and desires. How we all roughly function in the same way, and yet, vary in subtle and overt ways, all adding up to our distinct personalities. It may not sound like anything revolutionary, but something about the careful and steady progression of observations, explanations and examples gripped me. During my bachelor’s and master’s degree in psychology, I came across countless theories. Sometimes they related to each other, sometimes they contradicted, but they almost always appeared to operate within separate discourses, in their own little bubbles. In all my years of study I never came across such a comprehensive view on how all the smaller ideas and concepts fitted together. Although the books were more than ninety years old, they still seemed to have something ‘new’ to offer me.

Heymans’ Mission: Making Research Accessible

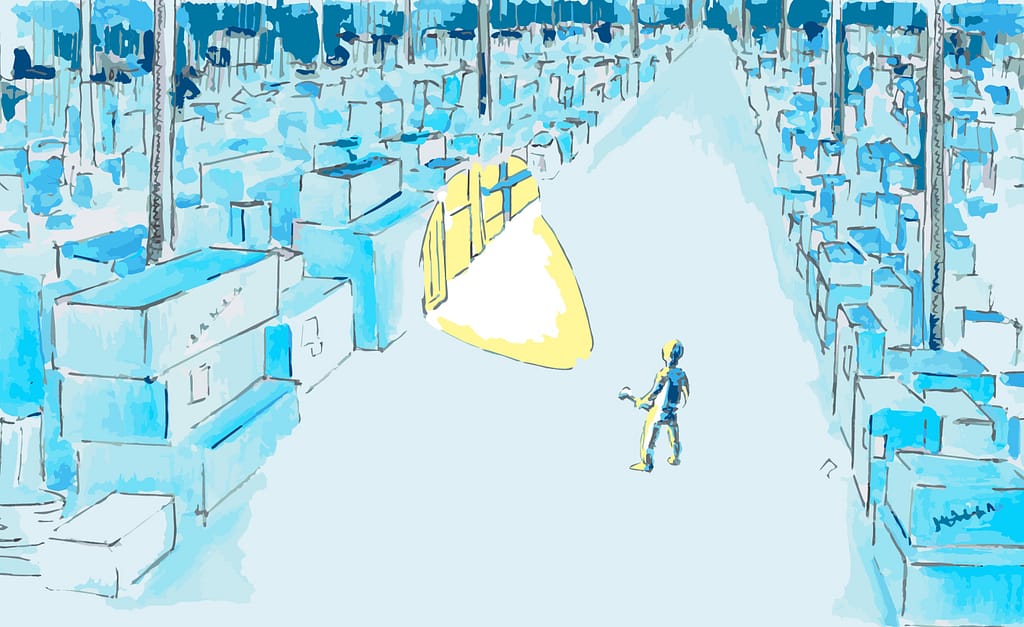

This intimate engagement with the text appeared to be precisely what Heymans had hoped for when he wrote his Inleiding tot de Speciale Psychologie. In his introduction, he explicitly stated that it was written for a general audience. He had kept production costs to a minimum to ensure the books could be sold at a low price. The books were based on years of research and decades of lectures. An analysis of over a hundred biographies and more than six thousand questionnaires had taken a small army of student-assistants and state-of-the-art statistical techniques to complete (oh, what they would have sacrificed for a basic calculator). But the results were worth it. With all these data, Heymans had found support for three basic dimensions of temperament that, in combination, could explain most individual differences. All in all, the methods and language had the rigor and complexity of academic work, but were supported by colourful metaphors and examples to help the material come to life. For example, he started his discussion of the elusive concept of consciousness by inviting the reader to imagine a dark, expansive warehouse, our occasional awareness of the thoughts and memories stored there represented by a small occupant walking around with a flashlight. Heymans had striven to make his work accessible, attractive, and useful to his audience.

And useful it was, at least to me. When my significant other told me that I had become a more understanding and pleasant partner since reading the books, I realised that – odd as it may sound – reading Heymans had indeed improved the quality of our relationship. As far as I could see, however, no one else was profiting. Back in Heymans’ day, the theory had experienced a period of popularity and broad engagement in Dutch society. His ideas about temperament and character had informed all kinds of societal debates: Should girls receive a different type of education than boys? Should temperament be taken into account when judging a suspect’s legal accountability in court? But nowadays, besides the occasional study replicating his findings or an honorary mention by modern personality researchers, no one is following up on this work. Even at the Heymans Institute, Heymans’ theory did not appear in the curriculum when I was a student. It seems to me that this theory only lives on on the nightstands of people like Frank. Buried under a mountain of new theories, it has all but disappeared from our collective memory.

A Problem Of Translation

I have come to realize that there are two problems –both related to translation– that keep the work from contributing to recent discourses about personality typologies. First, the book was written in Dutch and was then translated into German and French. However, as English gained more importance, ultimately taking German’s place as the global language of psychology, the lack of an English translation became increasingly problematic. This shift in the psychological landscape obscured Heymans’ work for an international audience. But there is a second translation issue, which has stood in the way of even a Dutch or German appreciation. The fact that the work is, by now, so old has had the unfortunate consequence that much of the language and ideas are undeniably old-fashioned. For example, referring to mental disorders that no longer exist, such as “hysteria” or “neurasthenia” would lead to unnecessary confusion. A translation for present-day audiences would require a certain amount of updating to make it accessible once again.

These barriers struck me as surmountable. All that would be needed was an English translation of the original books, perhaps slightly modernized and streamlined. Even better, I had the knowledge, the time, and the resources to make it happen. That thought made me excited, but also extremely uncomfortable. I had never written a book before, or published anything more than a blog post. Could I really do it? And shouldn’t I be focusing on publishing academic articles to improve my career prospects, rather than wasting my time on a popular book? The idea of becoming an author seemed so ridiculous to me, that I was too embarrassed to speak about it to anyone for several months. Hoping the thought would become buried under new ideas and projects, I pressed on.

But the idea did not want to be buried. Making this work accessible felt like it would be worth the trouble. First, with a face the colour of a tomato, I pitched it to my partner. Then, to a close colleague. Finally, to my supervisor. When the reactions varied from ‘sure, why not’ to ‘that sounds like a great idea!’, I decided to get over my discomfort and get to work. Figuring this was quite an ambitious project to take on by myself, I recruited a student — Corné, whose bachelor thesis had focused on this theory — as my co-author. Later, our team was strengthened by the addition of an illustrator, Tias Verdonk, and was supported by very generous colleagues and friends who helped to refine the product through review.

The result: roughly one year later, our very own book landed on my doormat. Thanks to the Open Access Book fund at the University Library, who supported us through the steps of production, the digital version was made freely accessible. When I held it in my hands, I remembered Frank, who showed me the value that such an old theory can still have today, and who inspired me to ensure that people can still profit from it tomorrow.

If you have grown curious to see if Heymans’ work resonates with you today, you can order a physical copy of the book or download the free digital version.

Image Credit: Both images are ilustrations created Tias Verdonk, published by University Groningen Press, republished with permission.

References:

Heymans, G. (1929). Inleiding tot de speciale psychologie. De Erven F. Bohn.

Vermeij, R.R., Vroomen, C.H.F.L. (2023). Heymans’ Cube. University Groningen Press.