How Your Body Reveals Your Personality: Exploring Embodied Dynamics Across the Lifespan

Our existence as embodied beings is inseparable from the environments we inhabit (Varela et al., 1991; Thompson, 2007; Johnson, 2015; Di Paolo et al., 2017). Psychological constructs such as personality often seem abstract, capturing how we behave, feel, and think; as well as the qualities that define our presence in the world. However, these patterns are not confined to the mind; they dynamically emerge and are expressed through our bodies and behaviors.

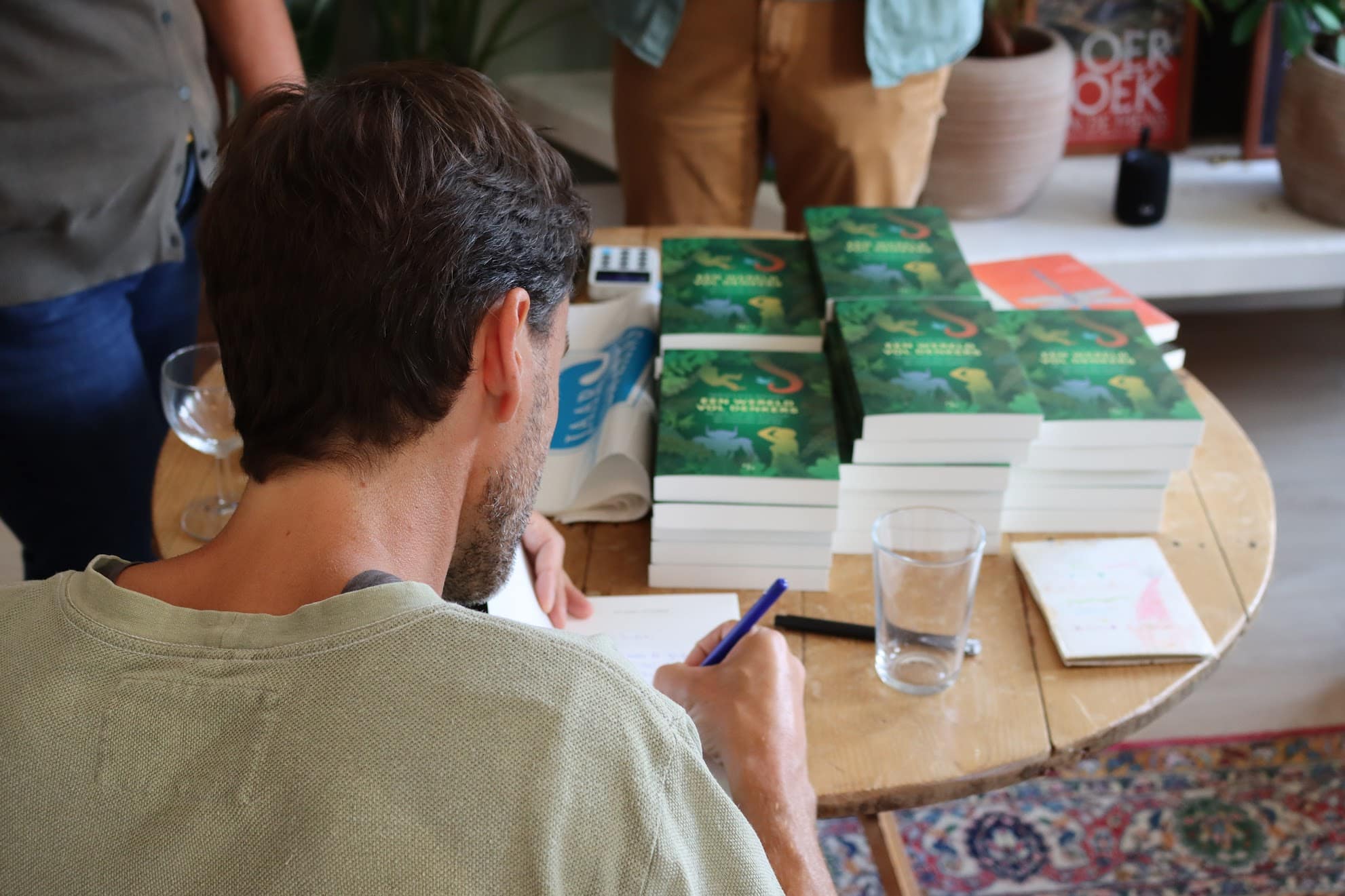

My PhD dissertation (to be defended in public on December 12, 2024), Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Dynamics in Personality Expression: A Complex Dynamical, Enactive, and Embodied Account, explores this notion in depth. Very subtle embodied dynamics exhibited when we interact with others, or while we reflect in solitude, manifest the emergence of behavioral patterns that constitute what we understand as personality traits.

Personality and Body Movement: A Dynamic Connection

In my dissertation, I adopted a complex, dynamic, enactive, and embodied approach. From these perspectives, personality emerges not as a static set of traits but as adaptive and dynamic patterns intrinsically tied to interactions with others and the world (e.g., Nowak et al., 2020). Personality traits manifest as dynamic patterns of behavior, emotion, cognition, and desires (Revelle & Wilt, 2021), observable in how we move, speak, and synchronize with others. These stylistic differences shape how we approach environmental affordances, appraise interactions, and maintain a coherent sense of self over time (e.g., Hovhannisyan & Vervaeke, 2022).

Personality traits manifest as dynamic patterns of behavior, emotion, cognition, and desires (Revelle & Wilt, 2021), observable in how we move, speak, and synchronize with others.

Two studies explored personality through the synchronization of body motion and speech during dyadic interactions, involving different conversation topics (Arellano-Véliz et al., 2024a, 2024b). Findings revealed that extraversion and agreeableness are significantly connected to interpersonal and embodied dynamics. For instance, extroverts and agreeable individuals showed greater bodily synchronization and dynamic coupling. In this case, the attunement of movement across multiple time scales with their conversational partners fostered positive feelings and social bonds. Extroverts also tended to enjoy swift conversations, maintaining prolonged coupling with their partners, while creating opportunities for their interacting partners to engage in. These findings suggest that introverts may benefit from extroverted conversation partners for enhanced social bonding; however, the results also suggested that meaningful connections can also flourish between introverts through mutual self-disclosure.

Extroverts and agreeable individuals showed greater bodily synchronization and dynamic coupling (…) the attunement of movement across multiple time scales with their conversational partners fostered positive feelings and social bonds.

In a different study, participants were asked to reflect and speak about themselves in solitude on various topics. These included a general self-introduction, reflections on their bodily and sensory experiences, and their socioemotional lives (Arellano-Véliz et al., 2024c). Here, emotional stability, or lack thereof, was reflected in the fluctuations of body movements. Individuals high in neuroticism (low emotional stability) showed unstable body motion patterns when talking about their bodily perception sensory experiences, and socioemotional life, which was also accompanied by negative affect. In contrast, those with more stable emotions exhibited more predictable and controlled movements (Arellano-Véliz et al., 2024c). Interestingly, people experienced higher positive affect after this task, which emphasizes the relevance of self-reflection even if no one else is around.

Individuals high in neuroticism (low emotional stability) showed unstable body motion patterns when talking about their bodily perception sensory experiences, and socioemotional life.

Temperament and Motor System Organization in Infancy

The research also extended to early development, investigating how temperament manifests through motor system organization in infancy. Collaborating with researchers from the Institute of Psychology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IP PAN) (see this related post by Zuzanna Laudańska), we identified early embodied correlates of temperament, such as negative affectivity in infants during interactions with their mothers (Arellano-Véliz, 2024d). The complexity and stability of infants’ motor systems—how movements are organized and their stability over time—were linked to early temperament traits. Another key finding from the infant studies was the role of maternal anxiety in influencing the infant’s motor system organization. Infants of mothers with elevated anxiety exhibited more unstable motor patterns, highlighting how early caregiving experiences—shaped by maternal emotional well-being—significantly influenced motor organization by 12 months of age. These results emphasize the embodied roots of emotional and behavioral development.

Linking Adult and Infant Development: A Continuum of Embodied Expression

Overall, the research developed over my PhD draws parallels between personality expression in adults, temperament in infants, and embodied dynamics. This suggests that embodied dynamics are essentially coupled to psychological processes. Just as adults express personality through speech and body movement across contexts, infants display early signs of these dynamics through interactions with their caregivers.

Ultimately, a core idea behind this research is that the stylistic differences we observe in people’s behavioral, affective, and cognitive patterns are fundamental to what we understand as personality (e.g., Hovhannisyan & Vervaeke, 2022) (and its precursor, temperament). At the same time, personality traits are embedded within complex dynamical systems—both at the level of individuals (dyadic systems) and in the coupled interactions between individuals and their environments.

Just as adults express personality through speech and body movement across contexts, infants display early signs of these dynamics through their interactions with caregivers.

Implications of this Research and Final Words

One of the most profound conclusions of this research is the reinforcement of the idea that psychological processes encompass patterns expressed through our body and its interactions with the environment (Varela et al., 1991; Johnson, 2015; Di Paolo, 2021; Nowak et al., 2020). Movements, gestures, and speech patterns are integral to how personality emerges and is expressed over time, both in social interactions and solitude.

Movements, gestures, and speech patterns are integral to how personality emerges and is expressed over time, both in social interactions and solitude.

The understanding personality as a dynamic and embodied phenomenon offers innovative ways to assess and address individual differences. For example, disruptions in embodied patterns may act as early indicators of emotional distress, mood disorders, or anxiety, while studies of temperament and motor system organization in infancy emphasize the connections between emotional and motor development and maternal well-being.

Finally, grounding personality and temperament in embodied patterns provides a coherent framework for understanding our experience of being in the world (Heidegger, 1988; Arciero & Bondolfi, 2009). This perspective opens up exciting possibilities for future research in personality, social psychology, and clinical psychology such as exploring how behavior, physiology, emotions, and thoughts dynamically interact and evolve across varying contexts. I am genuinely excited to continue exploring further, building on the foundations laid by this work, and to further investigate personality through this approach.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Ralf Cox and Saskia Kunnen; co-supervisor, Ramón D. Castillo; co-authors, Bertus Jeronimus, Zuzanna Laudańska, J. Duda-Goławska, and P. Tomalski; the participants of the studies included in this dissertation for their essential contributions; and the ‘Agencia Nacional Para la Investigación y Desarrollo’ (ANID, Chile) for funding my PhD (Scholarship 72200122).

References

Arciero, G., & Bondolfi, G. (2009). Selfhood, identity and personality styles. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470749357

Arellano-Véliz, N. A., Jeronimus, B. F., Kunnen, E. S., & A. Cox, R. F. A. (2024a). The interacting partner as the immediate environment: Personality, interpersonal dynamics, and bodily synchronization. Journal of Personality, 92(1), 180-201. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12828

Arellano-Véliz, N. A., Castillo, R. D., Jeronimus, B. F., Kunnen, E. S., & Cox, R. F. A. (2024b). Beyond words: speech synchronization and conversation dynamics linked to personality and appraisals. Research Square (Research Square). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4144982/v1

Arellano-Véliz, N. A., Cox, R. F. A., Jeronimus, B. F., Castillo, R. D., & Kunnen, E. S. (2024c). Personality expression in body motion dynamics: An enactive, embodied, and complex systems perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 104495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2024.104495

Arellano-Véliz, N. A., Laudańska, Z., Duda-Goławska, J., Cox, R. F. A., & Tomalski, P. Relationship between temperamental dimensions and infant limb movement complexity and dynamic stability. Relationship between Temperamental Dimensions and Infant Limb Movement Complexity and Dynamic Stability. Preprint available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4891778

Arellano-Véliz, N. A. (2024, November 4). Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Dynamics in Personality Expression: A Complex Dynamical, Enactive, and Embodied Account [PhD Thesis]. Retrieved from osf.io/8vsyg

Di Paolo, E. A., Buhrmann, T., & Barandiaran, X. (2017). Sensorimotor Life: An Enactive Proposal. Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1988). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927)

Hovhannisyan, G., & Vervaeke, J. (2022). Enactivist Big Five Theory. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 341–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-021-09768-5

Johnson, M. (2015). Embodied understanding. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(875), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00875

Nowak, A., Vallacher, R., Praszkier, R., Rychwalska, A. & Zochowski, M. (2020). In Sync. The Emergence of Function in Minds, Groups and Societies. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38987-1

Revelle, W., & Wilt, J. (2021). The history of dynamic approaches to personality. In J. F. Rauthmann (Ed.), The handbook of personality dynamics and processes (pp. 3–31). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813995-0.00001-7

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

Note: Featured image by Artem Laletin.

The original draft was written by Nicol Arellano, and edited by N. Arellano and Oliver Eksteins.