Cultural Diversity and Identity Threat

This blog post was written together with Jolien van Breen.

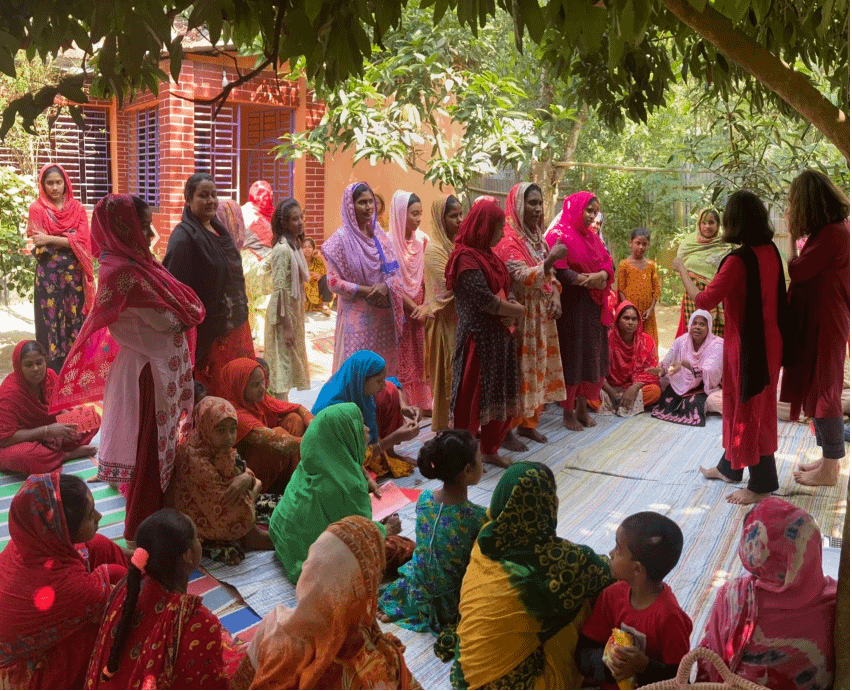

Nowadays, there are many opportunities to get to know people from different places, read global news, or to enjoy the most exotic food right in your hometown. The world is becoming more interconnected which opens up new possibilities and fosters communication between cultures (Sharma & Sharma, 2010). However, this process, known as ‘globalisation’, also has its negative sides. For example, dominant cultures can quickly overtake small cultural groups, leading to a loss of cultural diversity (Berry, 2008). Moreover, it has been suggested in the media that globalisation processes are linked to the revival of nationalistic and xenophobic attitudes in many European countries (Ariely, 2012). Groups with values different from our own are seen to be “invading our culture”, which may lead to increased support for political parties that advocate reduced immigration and prioritise interests of the cultural ingroup[1],[2]. In a current project, we are interested in whether this is indeed the case: Does globalisation increase negative attitudes towards outgroups?

Social identity theory

From a social psychological perspective, globalisation may constitute a threat to one’s social identity. Which is, according to Tajfel and Turner’s (1979) social identity theory, a person’s sense of who they are based on their group membership. Central to social identity theory is the idea that people perceive groups they belong to as different from other groups, they perceive a distinction between “we” and “they”. People derive their social identity from the unique characteristics of their own group, by contrasting it these to other groups. However, since globalisation leads to increased connectedness and similarity between groups, this may be perceived as a threat to the uniqueness of groups, so-called distinctiveness threat (Branscombe, Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 1999). When the group we belong to is under threat, this inspires a motivation to defend the group. More specifically, in case of globalisation, threat stems from the fact that groups are perceived as becoming more similar. Thus, ingroup members might want to create distance between their group and threatening outgroups, possibly leading to negative attitudes towards outgroups. In extreme cases, such processes might result in the development of discrimination and racism (Ommundsen, 2001). In line with social identity theory, the first hypothesis of this project is that:

“Rather than promoting intercultural understanding, globalisation might lead to increased prejudice between groups.”

However, we believe that globalisation may not lead to prejudice amongst all groups. For instance, minority groups might not turn to prejudice, but instead choose other strategies to cope with possible threats of globalisation. In general, unlike majority groups, minorities face pressure from the majority to assimilate, and need to “fight” this pressure in order to uphold their cultural values. This may imply, firstly, that they have more sophisticated strategies to deal with identity threats, because they are confronted with them more often. Secondly, strategies that work well for majority groups, such as trying to exclude outgroups, might not work for minority groups. Therefore, while we expect majority groups to reject outgroups after experiencing globalisation, we expect minority groups to use different strategies.

Studying the effects of globalisation

To examine these hypotheses, we studied the effect of globalisation on both a majority and a minority group. The majority group taking part in this study were German students. As members of a cultural majority group, they were expected to show negative attitudes towards outgroups. The minority group taking part were members of the ethnic and religious minority of Assyrians who are Christians and an indigenous group from former Mesopotamia – nowadays parts of Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Iran and Iraq (Demir, 2010). Due to massacres in the Middle East during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century the majority of Assyrians fled to Western countries like America, Germany and Sweden (Atto, 2011; Cetrez, 2011). Thus, Assyrians are not only a (cultural) minority in the countries they currently live in, but also a (religious and ethnic) minority in their country of origin, which makes this group particularly suitable for studying the minority perspective. For the Assyrian minority, then, globalisation and the homogenisation of cultures might lead them to perceive the majority (Westerners) more negatively, as the majority is threatening their cultural identity. However, rejecting the powerful majority group may not be an option for the Assyrian minority. Instead, Assyrians may choose to focus on other features of their ingroup identity, such as their language or history to emphasise the uniqueness of their ingroup.

“Assyrians may focus on their unique cultural heritage to preserve their social identity”

In sum, this project aims to examine the idea that globalisation might lead to prejudice towards outgroups, a trend which is evident in many European countries[3]. Secondly, it will test whether these divisive coping strategies arise amongst all groups, or whether there are groups who use more constructive strategies. Ultimately, through this project, we hope to provide insight into coping strategies for dealing with social identity threats that may provide the “best of both worlds”: promoting intercultural understanding, while preserving cultural diversity. In this way, it can help to integrate minority and majority perspectives in modern societies.

References

Ariely, G. (2012). Globalization, immigration and national identity: How the level of globalization affects the relations between nationalism, constructive patriotism and attitudes toward immigrants?. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(4), 539-557.

Atto, N. (2011). Naming and terminology. Hostages in the homeland, orphans in the diaspora: Identity discourses among the Assyrian/Syriac elites in the European diaspora (pp. 11-13). Netherlands: Leiden University Press.

Berry, J. W. (2008). Globalisation and acculturation. International Journey of Intercultural Relations, 32, 328-336.

Branscombe, N. R., Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, E. J. (1999). The context and content of social identity threat.

Cetrez, Ö. A. (2011). The next generation of Assyrians in Sweden: Religiosity as a functioning system of meaning within the process of acculturation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(5), 473-487.

Demir, S. (2010). Vergessener Völkermord an den christlichen Minderheiten im Osmanischen Reich von 1914-1918. (Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis). University of Bielefeld, Germany.

Ommundsen, R. (2011). Social identity threat, identification, and attitudes toward ethnic minorities in Norway. Studies of Groups and Change, 175-182.

Sharma, S., & Sharma, M. (2010). Globalization, threatened identities, coping and well-being. National Academy of Psychology, 55(4), 313-322.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology and intergroup relations (pp. 33-47). Monetery, CA: Brooks Cole.

Note: Image is modified version of image by Axel Naud (Flickr.com)