When Ethology Meets the Social Sciences: A Primatological Perspective on Human Behavior during Conflicts

Despite being just one, the human species has the privilege to be studied by multiple scientific domains. Perched in their fields, different disciplinary traditions rigorously followed their own perspective particularly in studying human behavior –even when facing similar research questions. This is the case of ethology and social sciences, two disciplines that adopted different approaches to the study of humans, with ethology providing evolutionary explanations to human behavior by largely looking at other animal species.

At the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, we aim to connect ethology to the social sciences by conducting a primatological analysis of human behavior during interpersonal conflicts that take place in public places. Our main question is: To what extent is human behavior in conflicts similar to that observed in other primate species and how can we explain this similarity? We propose a cross-discipline approach, both in terms of theory and methodology, to study the role of bystanders in conflict situations.

Over recent years, Close Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras have been adopted as a tool to access conflict events in public spaces. This allows for the first time to conduct unobtrusive real-life observations (Lindegaard & Bernasco, 2018). The video footage offers the opportunity to apply methods of ethology (i.e., the systematic study of animal behavior) on human behavior, thus allowing us to conduct a cross-species comparison to understand how conflict management mechanisms might be rooted in the evolutionary history shared with other primate species.

Our main question is: To what extent is human behavior in conflicts similar to that observed in other primate species and how can we explain this similarity? We propose a cross-discipline approach, both in terms of theory and methodology, to study the role of bystanders in conflict situations.

A behavioral analysis of the expression of emotions in conflict events

In our research, a first step to explore conflict dynamics in humans from a primatological perspective has involved the introduction of the role played by emotions, and in particular those related to a state of distress, in mediating bystanders’ response. In several primate species, it has been documented that a key predictor for intervention is the emotional state of the antagonists of the conflict. Their expression of distress –which is observable through specific behavioral indicators, such as self-directed behaviors– regulates their subsequent interactions and affects bystanders’ propensity to intervene (de Waal, 2008).

A first step to explore conflict dynamics in humans from a primatological perspective has involved the introduction of the role played by emotions, and in particular those related to a state of distress, in mediating bystanders’ response.

Does the expression of distress affect bystander intervention also in humans?

To answer this question, we first had to take a step back. The introduction of the effect of distress as an explanatory variable for bystander intervention requires that bystanders read specific signs that indicate that the person who was previously involved in the conflict is actually in a state of distress. What are these behavioral indicators?

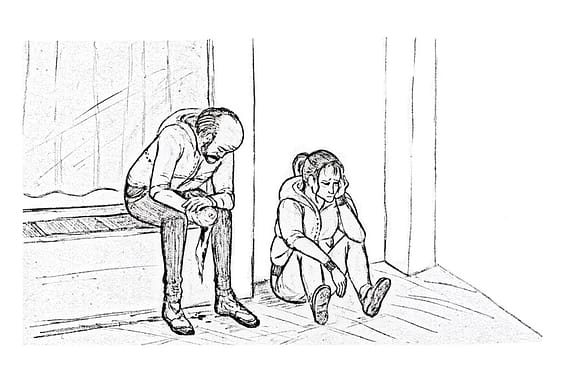

By combining a deductive procedure – based on the identification of distress-related behaviors already documented in the existing literature (Troisi, 2002) – and an inductive approach based on a qualitative observation of the video material, we developed a method to detect the distress-related behavioral repertoire displayed by people who took part in street fights recorded in public spaces of Amsterdam (Pallante et al., 2023). This behavioral repertoire is reported in the ethogram, a catalog including a qualitative description of the behaviors to be used for their subsequent systematic coding and quantification traditionally used in animal studies (Altman, 1974). Following previous literature, the behaviors we observed could be related to a specific underpinning emotional state indicating distress. Therefore, we included the behaviors observed into distinct categories referring to different emotional states (e.g., anxiety-related, anger-related, and physical sufferance), except some behavioral patterns that were frequently observed but did not refer – according to previous literature – to any specific emotional states (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1. The expression of anxiety-related behaviors (e.g., the girl on the right touches her face – behavioral code: Self-touching) and physical sufferance (e.g., the man on the left attends his injured hand – behavioral code: Self-care). Drawing by Lucia Berti.

Figure 2. The expression of anger-related behaviors (e.g., the woman on the left is talking by using the pointing gesture against a man who was not involved in the previous conflict event – behavioral code: Talking with aggressive gestures). Drawing by Lucia Berti.

Next steps

We assumed that the behaviors we interpreted as distress-related are the expression of a physiological variation, but in an observational study, this can only be inferred. Together with Dr. Laura Cuijpers from the Developmental Psychology department at the University of Groningen, we aim to couple behavioral observations with physiological measurements. We will test this in the context of self-defense training, connecting both physiological stress (e.g. heart rate variability) and observed behavior (e.g. fidgeting) in bystanders.

With the method developed to study the behavioral expression of emotions in video footage, the next step will be to assume bystanders’ perspectives to understand how the perception of distress-related behaviors impacts conflict dynamics. Exploring whether similar management strategies are rooted in a shared evolutionary history in the primate order or if they are the product of the unique social features characterizing our species has theoretical implications for the understanding of human behavior. We believe that interdisciplinary communication is necessary not only for a discipline’s self-improvement but also as a practice to build a shared perspective when different scientific domains meet similar questions.

References:

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour, 49, 227-266.

de Waal, F. B. (2008). Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279-300.

Lindegaard, M.R. & Bernasco, W. (2018). Lessons learned from crime caught on camera. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 55, 155-186.

Pallante, V., Ejbye-Ernst, P., & Lindegaard, M. R. (2023). An ethogram method for the analysis of human distress-related behaviours in the aftermath of public conflicts. Behaviour, 1, 1-37. DOI:10.1163/1568539X-bja10247

Troisi, A. (2002). Displacement activities as a behavioral measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress 5, 47-54.

Note: Featured image: Pickpik, Creative Commons license.