Does attentional bias modification constitute a suitable treatment for depression?

Second-year Psychology students participating in the University Honours College or in the Departmental Excellence Program complete a Research Seminar in which they learn to communicate science to various audiences, including the general public. For one assignment, the students write a popular science paper. This year a selection of these papers is published on Mindwise. Today’s piece is by Thole Hoppen.

Imagine the following situation: You take the elevator in a public building; the door opens and 4 strangers are looking at you. You cannot help it but your attention gets immediately drawn to that guy in the right corner who looks at you with an expression of rejection. As you are absorbed by the evil look of this guy, you do not really notice whether and how the other three people are looking at you. If you recognize yourself in this description, you may have a negative attentional bias for faces, meaning that you immediately pay attention to a most negative face, and may have a hard time to disengage from this face and, as a consequence, ignore other, potentially more positive, faces (Koster, Crombez, Verschuere, Van Damme, & Wiersema, 2006).

“attentional biases should be seen as existing on a continuum, with people with a psychiatric diagnosis closer to the extreme than healthy people”

It is thought that negative attentional biases, like the one illustrated above, may also exist in depressed people (e.g. Gupta & Kar, 2012) and contribute to the development and maintenance of depression (Beck, 1976; Beck, 2008; Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999). In other words, the tendency to focus immediately and more exclusively on the evil-looking guy in the right corner of the elevator is not just something that depressed people may have, but it could be associated with the process of becoming and remaining depressed. However, not everyone who shows negative attentional biases is or will become depressed. It can be seen as a risk factor rather than as a definite causal marker. Thus, attentional biases should be seen as existing on a continuum, with people with a psychiatric diagnosis closer to the extreme than healthy people. According to the World Health Organization (2013),350 million people worldwide suffer from depression. It is currently the leading cause of disability worldwide, causing patients to be severely impaired over a long period of time in numerous aspects of everyday functioning (Lecrubier, 2001). Further, the presence of one or more additional disorders co-occurring with depression, such as social anxiety disorder, complicates the disability experienced by sufferers.

There have been many attempts at treating depression. Among the established treatments are antidepressant medications, psychotherapy, or a combination. An additional treatment for depression has been proposed rather recently and focuses specifically on the negative attentional biases that depressed individuals often display. These attentional bias modification techniques have been introduced in an attempt to wipe out the negative consequences of attentional biases. Attentional bias modification usually seeks to modify attentional biases by the use of repetitive, computer-based training methods (Bar-Haim, 2010). To return to the example at the beginning of this blog post, these computer programs help you to disengage from the bad guy in the right corner and focus more easily on the friendlier-looking people in the elevator.

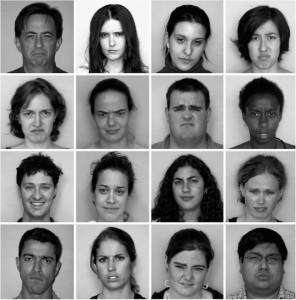

The “find the smiling face task” constitutes one form of an attentional bias modification intervention. The task is to find and click on one smiling face among 15 frowning faces as quickly as possible (see picture). Though this task is rather simple and can be done on any type of computer, in non-depressed individuals it has been shown to not just decrease negative attentional biases and increase positive ones, but also reduce stress measured by hormone levels, and promote confidence, self-esteem and work performance (Dandeneau & Baldwin, 2004; Dandeneau, Baldwin, Baccus, Sakellaropoulo, & Pruessner, 2007; Dandeneau & Baldwin, 2009).

The “find the smiling face task” constitutes one form of an attentional bias modification intervention. The task is to find and click on one smiling face among 15 frowning faces as quickly as possible (see picture). Though this task is rather simple and can be done on any type of computer, in non-depressed individuals it has been shown to not just decrease negative attentional biases and increase positive ones, but also reduce stress measured by hormone levels, and promote confidence, self-esteem and work performance (Dandeneau & Baldwin, 2004; Dandeneau, Baldwin, Baccus, Sakellaropoulo, & Pruessner, 2007; Dandeneau & Baldwin, 2009).

Given these encouraging findings, attentional bias modification is currently being discussed as a potentially effective, affordable, and convenient add-on treatment for psychological disorders like depression. But is the “find the smiling face task” indeed suitable for the treatment of depression? For the clinical usefulness of the task, it is of major importance to find out whether the beneficial effects of the “find the smiling face task” are robust. In other words, are they still there when people are sad, as depressed people are? Julian Mutz, Tobias Arbogast, and I set out to investigate exactly this question. Under the supervision of Lonneke van Tuijl, we studied whether the “find the smiling face task” remains an effective attentional bias modification when people are in a sad mood.

“attentional bias modification is currently being discussed as a potentially effective, affordable, and convenient add-on treatment for psychological disorders like depression”

The implications of our research depend on the outcomes of our study. If the task does not change attentional biases when people are feeling sad, then perhaps the method needs improving. It will probably be too early to say that it should not be used for psychological disorders involving sad mood, such as depression. If, however, the task can decrease negative attentional biases and increase positive ones even when people are feeling sad, then we have provided evidence for its clinical usefulness. In other words, by means of our research we will be able to tell whether training with the “find the smiling face task” could help you attend faster and more exclusively to friendlier people than to the evil guy in the right corner— even if you are feeling sad.

References:

Bar-Haim, Y. (2010). Research review: Attention bias modification (ABM): A novel treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(8), 859-870.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Oxford, UK: International Universities Press.

Beck, A. T. (2008). The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(8), 969-977.

Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (1999). Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Dandeneau, S. D., & Baldwin, M. W. (2004). The inhibition of socially rejecting information among people with high versus low self-esteem: The role of attentional bias and the effects of bias reduction training. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 584-602.

Dandeneau, S. D., & Baldwin, M. W. (2009). The buffering effects of rejection-inhibiting attentional training on social and performance threat among adult students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 42-50.

Dandeneau, S. D., Baldwin, M. W., Baccus, J. R., Sakellaropoulo, M., & Pruessner, J. C. (2007). Cutting stress off at the pass: Reducing vigilance and responsiveness to social threat by manipulating attention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 651-666.

Gupta, R., & Kar, B. R. (2012). Attention and memory biases as stable abnormalities among currently depressed and currently remitted individuals with unipolar depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry 3: 99.

Koster, E. W., Crombez, G., Verschuere, B., Van Damme, S., & Wiersema, J. (2006). Components of attentional bias to threat in high trait anxiety: Facilitated engagement, impaired disengagement, and attentional avoidance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1757-1771.

Lecrubier, Y. (2001). The burden of depression and anxiety in general medicine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(Suppl8), 4-9.

Van Damme, S., & Wiersema, J. (2006). Components of attentional bias to threat in high trait anxiety: Facilitated engagement, impaired disengagement, and attentional avoidance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1757-1771.

Author: Thole Hoppen

Author: Thole Hoppen

Bio: Thole was raised with three siblings by a single mom in a German village close to the Dutch border. In 2013-2014 he was a second-year Bachelor student of Psychology and delighted to be part of the Honours College. He is interested in clinical psychology, as he wants to work for Doctors without Borders in the future. Thole would like to help people overcome psychological problems and live happier lives. The Honours research practicum was a very interesting experience for Thole, which he really appreciated.

NOTE: Image by peddhapati, licenced under CC BY 2.0